Today is the second post focused on women singer-songwriters in the late sixties and early seventies.

Yesterday’s post was about Carly Simon’s revenge song against the Hollywood bros who used and discarded her, “You’re So Vain.”

Today’s post is about a singer-songwriter who was remarkably supportive of other musicians in the midst of her own staggering, and largely secret and hidden, parade of trials and tribulations.

Song of the day

“I was living platonically at folk-singer Judy Collins’ apartment on the Upper West Side in between my own apartments,” Al Kooper tells us in his fascinating autobiography Backstage Passes & Backstabbing Bastards: Memoirs of a Rock ’n’ Roll Survivor. “Judy, the number two female folk singer behind Joan Baez, was a wonderful, generous woman. Her apartment was the folk music salon of the mid-sixties. People like Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Phil Ochs, and others would make the pilgrimage to her digs and enjoy her hospitality and earth mothering.”

No doubt there was a pilgrimage to Judy’s apartment not only because she was hospitable, but also because the 27-year-old Judy was both strikingly attractive and remarkably talented, having studied from childhood with orchestra conductor and pianist Antonia Brica and debuting as a virtuoso classical pianist at age thirteen. (Judy would team up with Jill Godmilow to produce and direct a 1974 documentary about Brica called Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman, nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2003.)

Despite Antonia Brica’s belief that Judy had a very promising future in the classical world, Judy fell in love with the folk music of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and other folk artists and switched to the guitar. Marrying at age 19, she supported her graduate student husband and baby son with clerical jobs and a burgeoning career as a folk singer. Discovered while performing in Greenwich Village at the Village Gate, she signed with Jac Holzman of Elektra Records and released her debut album, A Maid of Constant Sorrow, at age 22.

And what constant sorrow Judy had! As she details in her book Cravings (2017), as her touring and recording career grew, so did the challenges she was grappling with behind the scenes. Right after recording A Maid of Constant Sorrow and debuting at Carnegie Hall, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, consigned to a sanatorium for six months, and forced to get an advance on future albums because she had no health insurance.

She was engaged in a protracted, expensive, and acrimonious custody battle with her husband (and his family) over their son Clark, who at one point was kidnapped from her home and moved across country by her husband. He eventually won sole custody, a devastating decison that she believes went against her because she admitted to being in regular psychoanalysis.

Judy also suffered from body dysmorphia disorder, as have so many women in the public eye, using smoking, a cycle of bingeing and fasting, obsessive exercise, and prescription speed and downers to stay thin. She later came to realize and acknowledge that, like her father, she was also an alcoholic. (She kicked both the smoking and alcohol addictions in the seventies.)

On top of all this, her career was threatened by losing her voice every few weeks, the constant touring and recording (and no doubt also the smoking) taking its toll on her untrained vocal chords. Judy was not willing to go down without a fight, however. Applying the discipline she had learned practicing classical piano, she embarked on daily lessons with the renowned Max Margulis (who she shockingly discovered had an apartment two doors down from hers). Using his bel canto technique, she went from a worn-out voice that reached barely an octave to “one long and uninterrupted line of three octaves,” and continued to work with Max and hone her voice for the next 32 years.

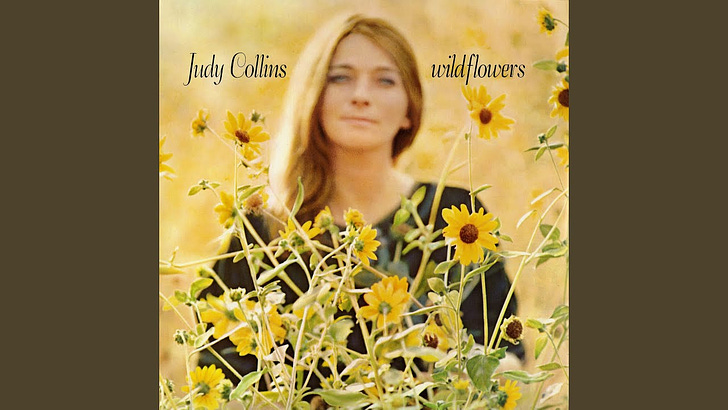

So is it any wonder with all of the above that her rendition of “Both Sides Now” hits us in the gut with its emotional authenticity and intensity? Judy recorded this bittersweet song by the still largely unknown Joni Mitchell for her Wildflowers album, the first album in which Judy ventured to include her own compositions.

She was finally coming out, and people responded with enthusiasm. The album reached #5 on the Billboard 200 and, after its release as a single in 1968, “Both Sides Now” went to #8 on the Billboard Hot 100 and #3 on the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart. It also won her a Grammy for Best Folk Performance.

Let’s listen to the song, and then I want to circle back to where we started.

The story is actually richer and more heartwarming than what I’ve written above. Not only did Judy serve as earth mother to Al Kooper and other musicians, offering them a helping hand, a friendly ear, and access to a Steinway grand piano, but she also helped many up-and-coming singer-songwriters such as Leonard Cohen, Randy Newman, and Joni Mitchell gain much-needed visibility by including their songs on her albums. As we will see tomorrow, she played an instrumental role in Joni Mitchell’s career in more ways than one.

With her book Cravings, Judy also moved beyond the music community to share the lessons she learned in her journey to recovery with everyone. A marvelous gift from, as Al Kooper said, a wonderful, generous woman. For me personally, Judy is also a powerful role model of how to be generous despite whatever trials and tribulations life happens to throw at you.

Song credits

Songwriter - Joni Mitchell

Judy Collins – guitar, keyboards, vocals

Technical

Joshua Rifkin – arranger, conductor

Mark Abramson – producer

John Haeny – engineer

Thank you for shining the spotlight on Collins. I was in elementary school when I first heard her, and she became my benchmark for beautiful voices, both consciously and subconsciously, for the rest of my life. Later on I would find Linda Ronstadt, Annie Haslam and Lara Fabian, but Judy always stayed with me. In another thread here I mentioned that her version of "Both Sides Now" remains one of the most arresting, perfect recordings I've ever heard. Thank you for also bringing out a little bit of her backstory.

Another anthem resurfaced from near obscurity; Judy Collins' voice was there to greet many an intrepid sunrise, a soothing for the anxious soul.