"The Want of a Nail" by Todd Rundgren: Is THIS a protest song?

The protest song series

I’ve been engaged in a conversation with a fellow Substack music writer on what qualifies as a protest song.

He suggests that at least one of the songs profiled in a recent post should not be viewed as such.

Readers have also raised this issue.

It’s also something that a few of us were puzzling about earlier in this series.

What qualifies as a protest song? Even further, what qualifies as an effective protest song?

You might recall Dewey Finn enlightening his students in School of Rock that rock ’n’ roll is all about ‘sticking it to the Man’. That is, until effin’ MTV ruined rock ’n’ roll for good in the early 80s.

Does this suggest that all real rock songs — that is, those before the corruption of the money-grubbing 80s and MTV — are, by definition, protest songs?

Or — since that seems rather extreme — should we define all real rock songs as protests not necessarily against the Man, but against something we’re not happy or pleased about, namely:

what we want but don’t have

what we have and don’t want to lose

what we’re being told to do

what’s wrong with the world

what’s wrong with someone else (who won’t love us the way we want to be loved)

and so on and so forth?

After all, rock is not pop or easy listening, for crying out loud. There are important distinctions, even if there is some genre fluidity.

Think about the extremes in rock, like heavy metal and punk. What might they be telling us about the ultimate raison d'être of this musical genre?

Or, to swing to the opposite extreme, should we view official or valid protest songs as only those associated with an important cause or social or political movement (no matter the genre)?

Are we in danger of trivializing and puncturing the power of real protest songs that are intended not just to protest but to bring about real and meaningful change?

In other words, do we need to tread more carefully, and be more mindful, in our use of this term? Do we want to avoid robbing artists and movements of the power of legitimate and important protest music?

Or are we fooling ourselves in thinking that protest music has any legitimacy or purpose beyond communicating and communing with others who already think or feel in the same way that we do? Is it a form of in-group sermonizing or propaganda?

No easy answers, are there? It’s something I plan to explore further in my summary of what we’ve learned from this series.

I’m interested in your views. And, of course, I also intend to consider (but not be limited or swayed by) how protest songs are defined by various experts and opinion makers (including fellow Substack authors).

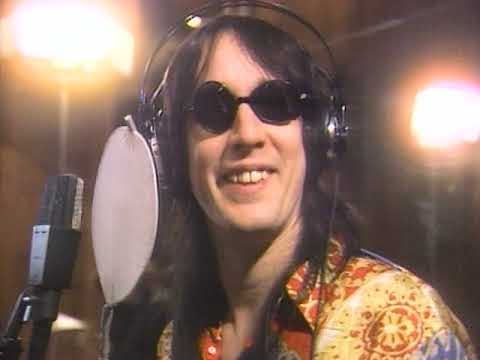

Towards that end, I was re-listening to the subject of this post — a brilliant song by Todd Rundgren, “The Want of a Nail,” which is the lead track on his Nearly Human album (1989) — and asking myself ‘does this qualify as a protest song’?

Thoughts? Reactions?

Todd’s live studio version with Bobby Womack is at the top of this post, his performance with Daryl Hall and band on Live from Daryl’s House is below.

The lyrics are here, clearly based on the following proverb that’s been around at least half a millenium, whose original source is unclear, but which has continued to provide inspiration to writers, poets, and modern-day happening music-makers like Todd:

“For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.”

Whatever your intellectual reaction, I think you’ll enjoy this joyous song — and wish you had been there at either or both of these recording sessions. Have a good weekend.

To each his own. I have a bias against Todd, who mistreated our college newspaper staff when he played at our school.

Personally, I don't think anybody should be the gatekeeper of what is or isn't a protest song. What it says or how it is interpreted by one person is just as valid as it is to the next, even if they differ in interpretation.

Some protest songs are obvious—Rage Against the Machine's "Killing In the Name Of" or Country Joe & The Fish's "An Untitled Protest," for example. Others may be far more subtle. REM's "Cuyahoga" is a song about how we have, and are, killing our environment. However, many people today might not realize that simply because the story of the Cuyahoga River as a symbol of man's poisoning of nature is 55+ years old.

And yet other songs may be interpreted by the listener in a way that was never the original intent of the song, but perhaps it becomes a protest to the listener—for example, a song that helps somebody feel empowered to stand up for something, think differently, to interrupt microaggressions, or even to walk out of an abusive or toxic relationship. That all becomes a form of protest against something.

I also firmly believe that what a piece of art says to you is just as valid, if not even more so, than the artist's reasons for creating it. Ultimately, you are the listener or viewer of the art. Educating oneself on the why behind the piece is always important, but it never means one's interpretation is wrong or invalid. It is subjective, and there is already far too much gatekeeping in the arts.

Just my two cents, however.