Todd Rundgren as a songwriter and performer: The Creator Series #3

His early years including The Nazz

This post covers Todd Rundgren’s career as a songwriter and performer up to and including his Nazz years.

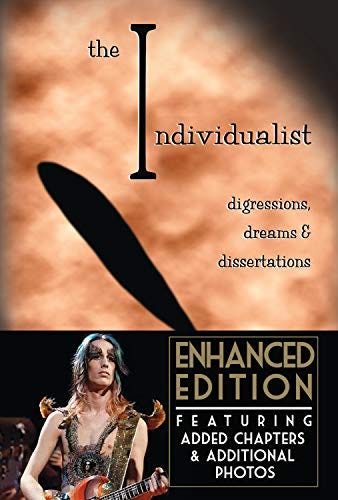

Todd is a one-off, and his autobiography is no different. I ordered a paperback copy of the Individualist: digressions, dreams & dissertations (2018) and unexpectedly received a hardcover (much to my delight). The pages are glossy rather than matte, the table of contents presented across two facing pages in six columns, and the title of every chapter a single word. (Although to stay within his design parameters he named a chapter about Meat Loaf “Meatloaf,” which may confuse anyone desiring his culinary reflections. They are sadly missing from this volume, which is “only partly finished,” ending on the day of his wedding at age 50. He’s now 76.)

Each chapter is one standalone page in three paragraphs: “a recollection of something that I witnessed, a subjective assessment of my state of mind in either experiencing or remembering the episode (or a haphazard combination of both), and… a conclusion, a statement of plain facts, or simply soapbox proselytizing.”

Reading one page of his autobiography, if you read the right page, justifies the purchase price. For me there were a lot of pages like that.

You can read the chapters in order or graze wherever takes your fancy. It matters not as each page is complete in and of itself. I loved the bite-sized format, each bite a juicy piece of sirloin steak, a mouthful of avocado toast, or a spoonful of mint chocolate chip ice cream. In other words, worth the effort.

He doesn’t dish the dirt, despite the misleading book description written by the marketing people, but he does talk about professional and personal relationships and give pithy insights into how he experienced them. You can’t look for someone — or anything — because there’s no bloody index. The chapter titles give a clue, e.g., Badfinger or Bebe, but the book also doesn’t give dates and follows a loose chronological order but not always. Sometimes he revisits a topic that seems to be on his mind, you thinking ‘didn’t I read this before?’ only to realize he’s taking it down a different track. And sometimes I wasn’t sure what album he was talking about, not to mention he refers to A Wizard, A True Star simply as AWATS.

Todd of course did the cover art and layout design, and it’s clear he did the writing and editing because there are some grammatical mistakes here and there an editor would easily pick up. Ever the innovator and, indeed, the individualist we know and love.

My feeling on finishing it — what a gift. Never one to shy away from sharing what he really thinks, he’s now tempered his honesty with the acquired empathy and self-understanding of an older man who’s been around the block many times and learned from a lifetime of pursuing his passions and taking risks. He shares and reflects on his failures as well as his successes, and owns up to what he views as his personal failings. It’s clear that, even now, he’s one of those guys who continues to be perplexed by women and trying to do the right thing but not always sure what that is. That’s why it’s heartwarming to see the many glossy color and b&w photos from his life, including with his wife and kids.

Because there’s so much about his artistic process as a performer, songwriter, producer, and innovator in this book, as well as in his numerous video interviews and talks, we will cover him as a creator over several posts. We’ll also hear many of the songs he performed or produced in the coming two weeks.

Given how influential he’s been on other musicians, and how prolific he’s been in producing and performing his own music over his sixty-year career, we could design a course or even a series of courses about him. If you’re not familiar with his work or need a refresher, you might benefit from watching this 11-minute video, which gives a quick overview from his childhood into the 1970s:

I will also include quite a few quotes from his book and embed a number of videos so you can hear things in his own words. I think you’ll enjoy hanging out with Todd as much as I have. If you’re a reader, I highly recommend investing in the book.

Now, on to Todd the Creator…

Becoming a musician

As we learned with James Taylor and Carole King, Todd was immersed in music from a young age and quite literally mesmerized by it:

“My parents had an RCA 45 RPM player that probably was supposed to be shared but which I hogged at an early age… Many of the discs were colored vinyl which I would stare through as the music played for hours. I’d sometimes sit in the kitchenette and listen to the radio while my mother cooked and sang along with Patti Page and Johnny Mathis… There was music on the TV, like Perry Como and Mitch Miller and occasionally something interesting on Ed Sullivan. Then my dad built his own HiFi from plans in Popular Electronics so we began to hear LPs of classical music and show tunes, long form music which kept me rapt for as long as my dad would listen — he would never let me touch the turntable. I eventually got a crappy portable stereo of my own so that I could start buying the records I wanted to hear.”

Keep the fact that his dad built a hifi from scratch in mind as we go forward. As you’ll see, that “I’ll just build it myself” attitude will pervade Todd’s career.

From listening to his dad’s classical records, Todd also gained an insight that would have an effect especially in the more experimental parts of his career:

“There is an entirely other effect created by wordless music, when the composer must paint a picture in the listener’s mind using sound alone… cuing everyone how they are supposed to feel at every moment. Sometimes the lyric just takes the air out of everything.”

As a kid Todd messed about with quite a few instruments, starting with a six-string he found in the basement that he sawed at like a cello with a coat hanger. He learned to play a bit on his sister June’s clarinet, but couldn’t handle the fingering on a flute. He also liked to express himself on the piano in his grandmother’s attic. What stuck was the guitar, his parents getting him an acoustic for 25 bucks in a deal that required “the horror” of eight weeks of music lessons in which he was “staring uncomprehending at black spots on ruled paper.” (He does not read or write music to this day.)

He got good at picking out tunes he heard on the radio, and even asked if he could play Ricky Nelson’s “Lonesome Town” for the other kids at a weekly dance lesson and socialization class, where some prankster managed to throw a balled-up napkin straight into his guitar hole. “Undeterred, I played on.”

His dad took him to see Forbidden Planet and this sparked his interest in rebuilding his hero from the movie, Robby the Robot, and in the atonal electronic music soundtrack. He believes that these two interests later manifested in his obsession with computers and his cornering of the local record market in Eastern European records involving strange instruments and aural pastiches. (Not to mention he found said records in the bargain bin.)

In reviewing his childhood engagement with music, he offered two key reflections on his motivation and eventual direction:

“I guess it always was and probably will be music that defines my expression. It gave me a toehold on life and allowed me to justify my Bohemian inclinations. Being considered a musician is a special and difficult privilege to the extent that parents should rightly discourage their children from considering such an avocation. Who needs the competition?”

“… we acclimate and eventually gravitate to the music we experience in our formative years, whatever that turns out to be. Eventually you turn into your dad — ‘That’s not music! Back in my day we had real music.’”

His short-lived but successful high school band

“There was something wrong with you if you didn’t envy the guys who managed to learn to start and end a song together to the adoration of the opposite sex.”

Hence Todd and his buddy Randy put together a pop band called Money doing some R&B, folk rock, and English band covers:

“You always dream that the band you are in is the one that will make it. Especially if you are clueless about how the music business works. You have discipline-free rehearsals and play a few gigs for low expectation audiences and practice running away from groupies in your high heeled shoes (don’t wanna fall like George did in Hard Day’s Night),” as well as growing your hair and wearing cool clothes.

Todd became interested in the slide guitar after listening to the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and hearing Mike Bloomfield and Jeff Beck. Finding a pulley from a card sorter in a box of computer parts an uncle had given Randy, he filed the flanges off and fashioned his own three-string slide. “Such is the makings of a ‘style,’” he said, given his unawareness at the time that most slide players use open tunings.

During senior year, Money played at dances, frat parties, and hops and he thought they “got pretty good,” but the band just organically fell apart when school ended.

He mail-ordered a Radio Shack Asian import guitar and, after he took possession, answered ads for guitar players. Waiting in the bus terminal to come home from an audition, a guy persuaded the empathetic Todd to lend him the guitar and immediately absconded with it.

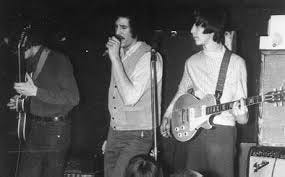

Defining his identity through Woody’s Truck Stop

Todd met a guy in a music store he frequented named Joe DiCarlo who soloed for five minutes on a drum set and wowed everyone. He and Joe decided they wanted to form their own band, but ended up joining Woody’s Truck Stop when they went to see the group play at the Artist’s Hut. Absent a drummer, Joe sat in and the band asked him to join, but he said he would do so only if they hired Todd too.

So Todd replaced the rhythm guitarist, who could now front and play harp, and proceeded to make his mark with his three-string slide made out of a shaved-down flange. As he realized when he joined, “I was to be the Elvin Bishop of the band [guitarist for the Paul Butterfield Blues Band] — integral to be sure, but even I wasn’t positive what an Elvin solo sounded like.”

The band rehearsed on the second floor of a motorcycle repair shop across the street from a black bikers’ hangout, a bunch of white guys in the heart of a black area of Philly, and Todd moved into bass player Carson Van Osten’s basement apartment.

The Truck Stop guys drove to New York City regularly to catch music and saw a double-bill of Cream and the Who at the Murray the K show. Citing those two bands as two of his biggest influences, Todd kept his musical gaze on the UK, but his bandmates would soon become focused on music coming from the West Coast and their paths would diverge.

Truck Stop was doing very well in Philly, but the guys followed keyboardist and leader Kenny Radeloff to college in Boston, where they struggled to get gigs and lived a pauper lifestyle on shoplifted food and Halloween candy obtained trick-or-treating with paper bags over their heads (pretending they were college kids in a fraternity initiation ritual). The arrival of snow drove them back to Philly. The band (not including Todd) then went psychedelic and got into ‘trips’ on drugs after the Grateful Dead’s first record came out — what Todd considered that “loathsome West Coast influence.”

As Todd explains, “The music of the west is like the west — earthy and sentimental and disorganized and it appeals to the cowboy ethos. I grew up in the colonies. My musical leanings are eastern — London, 19th & early 20thcentury France and Germany. Africa, India and beyond. Broadway! And a little south Memphis, Muscle Shoals, Nawlins… Detroit, but certainly no further west than Chicago.”

You can find a timeline and photos for Woody’s Truck Stop, compiled by rock historian Bruno Ceriotti from multiple sources including Todd Rundgren, here.

Carson was fired in favor of some cello prodigy who had no idea how to play bass and opted for his cello, making Todd realize that it was time to follow Carson out the door.

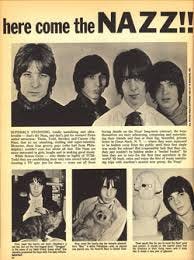

Forming and leading The Nazz

Todd and Carson decided to form their own band, and poached drummer Thom Mooney from The Munchkins and keyboardist/vocalist Stewkey Antoni from duties as a moaning frontman on a Wurlitzer piano for some unnamed brand new outfit, breaking up both bands in the process. They named themselves The Nazz from a song on the B side of a Yardbirds tune, fancied themselves a Who-Beatles cross, and “immediately ruled a 20 square block area” of Philly.

Todd and Thom Mooney went to see The Who open for the Mamas and the Papas and searched out Roger Daltrey at the downtown Holiday Inn bar afterwards. “Fan-boying him,” they got approached by John Kurland asking if they were in a band, and the next day performed a few covers and some original songs for him and his associate Michael Friedman in their studio over a record store. After some consultation, John and Michael offered to manage them and soon they were saying goodbye to Philly and hello to New York. Or rather to Great Neck on Long Island, where they could afford a house with four bedrooms and rehearsal space.

Despite being an hour east of Manhattan, Todd took full advantage of the management relationship and of easy access to the music scene in New York City. “The management office was in an especially tony street where you might run into music and acting celebs going in or out of a house in a neighborhood. This represented the other perk of my city trips: access to the piles of promo records that came into what used to be a publicists’s address. Who is this ‘Buffalo Springfield,’ this ‘Iron Butterfly,’ this ‘Vanilla Fudge’?... Some of it may even have influenced The Nazz.”

Although they had a manager, they didn’t have a producer, so the band did some showcases at the Café a Gogo, one being an audition for Cream’s producer, Felix Pappalardi. “I liked what he had done on a Youngbloods record and he wanted to work with us, but after I heard Disraeli Gears I thought the drums sounded wimpy so I changed my mind.”

Todd had an evolving sense of who he wanted to become as a musician that ultimately conflicted with their management’s approach as well:

“Being publicist, John Kurland had distinct ideas about how to promote the band and had the connections to pull off his grand scheme. Even before our first record we were getting features in 16 Magazine, the premier music publication for adolescent girls… It was a little weird, Kurland’s theory of reverse success: get famous then do something to be famous for. Who knows, it might have worked out in the long run but it made it hard sometimes for the band to figure out its purpose. Are we players or pinups? And we kind of skipped the bonding that touring would have forced on us, not to mention the potential improvement in our performance. At least we still had the wardrobe.”

Based on his experience, Todd offers this advice to someone just starting out — get out there and play play play:

“Do what you do. A painter paints, a dancer dances, a player plays. So often musicians claim to be waiting for a situation to arise before they get really serious. No point writing too much without that record deal. Don’t want to play for less than 100 people. But no matter how much you woodshed you’ll never know you can affect somebody until you get out there and play for them. And if it turns out you suck, at least you can stop wasting your time.”

The Nazz was desperate to find a producer for their first record. “For some reason we thought that the producer had something to do with the ultimate sound quality and that the best sounding records were made in England so we tried but failed to get a British producer. Ultimately we made our choice based on the sound of a single song by The Shadows of Knight, a cover version of Gloria.” Bill Traut agreed to produce their record, “apparently the old-fashioned way which involved little input about sound or performance and a lot of time reading the trades.”

As we saw with Carole King, not knowing how to do something never stopped Todd from attempting to do it. He planned the thirty-some piece orchestral arrangement for one of their songs and wrote all of the scores for the instruments, in his inexperience taking some of them outside of their ranges but getting kudos from the players for his efforts.

He also didn’t know that they had to join the Musicians Union before they could enter a union studio, even to record demos.

Hanging out at the union office and seeing old players there “waiting around for a joyless gig in their threadbare suits,” he realized that he’d “Never thought about the money, let alone playing music out of a fakebook. I was doing it for the love. The love of the music and the hope that it would make someone love me.”

In the video below, Todd talks more about what motivates his music, as well as the important freedom he has gotten to make the music he wants to make, rather than being beholden to commercial interests and constraints, by becoming a producer and setting up his own studio:

Unhappy with Bill Traut’s final mix for their record, Todd did overdubs and remixes on two songs, “Open My Eyes” and “Hello It’s Me,” again learning by doing. He created a desired flanging effect for “Open My Eyes” by monkeying around with a tape machine. When their debut album called Nazz was released in October 1968, it was those two songs that would be selected by the label as singles. “Hello It’s Me” would hit number 66 on the Billboard Pop Singles chart and “Open My Eyes” would eventually be considered a psychedelic rock classic — not bad for a debut album!

Even while playing with The Nazz, Todd continued to hone his chops and advance his knowledge of music. He met Moogy Klingman watching Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention doing a soundcheck and began jamming with him for fun. He also fell in love with Laura Nyro’s second album, Eli and the 13th Confession, and as a result “started gravitating toward the piano as a compositional tool.” Through John Kurland knowing David Geffen at Columbia, he got a couple of meetings with Laura at her apartment. She ended up asking him to be her bandleader and he even considered accepting because he was musically dazzled by her, but turned it down to remain with his own band. His “dazzlement” and her influence on his music would soon have repercussions.

The Nazz decided to record their second record at brand-new Trident Studio in Soho, London. Todd declared himself producer “to mixed reviews.” Within a day of working at Trident they were blackballed from any union venue or studio by the British Musicians Union. They spent the rest of their two weeks in London shopping for cool clothes and “sneaking in” a press showcase at Ronnie Scott’s.

Thom and Stewkey were now trying their hands at songwriting and, as Todd recounts, “there was growing indignation at my hogging all the composition to the point that the record swelled to a double album bloated with mopey songs that I sang in a flat style and that confused everybody. [That Laura Nyro influence!] After it was mixed a consensus grew that the record should be pared back to a single LP, which angered me and pitted me against the rest of the band.”

During a heated dispute Carson announced he was quitting. “Kurland began playing both sides of the dispute and when he got caught I felt betrayed and quit the band as well. Ironically, Hello It’s Me was taking off at radio. The band got a few gigs in far flung places and I would show up to collect a paycheck, never knowing who would be on the bass.”

On leading the band, Todd mused that growing up a troubled loner “would not help me with the diplomatic and psychological nightmare of post-adolescent personality management. If I was to ever develop ‘people’ skills as such, it would be many years and many unpleasant studio experiences later. I suppose when you’re that age you just get used to a certain amount of constant animosity.”

Todd reflects further on what went wrong all those years ago:

“I had no plan B when The Nazz imploded. I had always planned for success. Maybe because we had always pretended we were already successful the hard work of achieving it wasn’t what we were expecting. Somehow we lost the vision of what we were supposed to be. The fact that our management kept us off the road for so long in an attempt to drive up demand probably didn’t help. We forgot what it was like to play together for an audience. The Beatles in reverse.”

We’re going to listen to both The Nazz’s and Todd’s versions of “Hello It’s Me” later this week, so let’s end this post by listening to “Open My Eyes,” which reached number 112 on the Billboard Pop Singles Chart:

Coming attractions are two more posts on Todd Rundgren as a creator and many of the songs he wrote/performed and produced.

Great post Ellen! Todd is Godd in my book, and I first saw him live in 1973 at the free Central Park gig where he recorded "Sons Of 1984" (I can find my face on the back cover of the "Todd" LP). I last saw him about 2 weeks ago (for the 13th time) at the Pantages Theatre in Tacoma, WA. It was a great show - ever the individualist, he eschewed the 'hits' and chose to play deep album tracks for almost 2 hours before encoring with a quick medley of "I Saw The Light/Can We Still Be Friends/Hello It's Me", plus two more familiar songs from his vast catalog. Todd was in fine form at age 76, both vocally and on guitar, and the crowd was with him the whole show - I can't think of many artists who could pull that off, i.e. hold an audience's attention for that long with songs that were most likely unfamiliar or long-forgotten to any but the hardest-core followers. I consider myself one of those, and even I had trouble placing a few of the tunes he chose to play. I look forward to your upcoming posts, and thank you for recognizing an artist that really does qualify for that rarest of "G" words - genius!

That is a great write-up and a nice tribute to Todd Rundgren as a musician and a memoirist.

I have to admit, that I was a little distracted reading it, because I think of "The Nazz" as a reference to Lord Buckley -- which looks like it might be the origin of the term: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/blindmanfr/the-nazz-are-blue-t239.html

-----------------------

The Mojo Magazine (March 2000) has this to say when asked about Todd Rundgren's band:

"Legend has it that the term "The Nazz" was coined by Lord Buckley, an American comedian whose monologues were couched in hip, black, jive-talk and Baptist cadences. In this groovy style, his monologue The Nazz retells stories from the New Testament with jesus as "The Nazz", a corruption of The Nazarene. Later, Mods used the expression to mean 'The Ultimate', hence its use in a Yardbirds song. The Nazz, who seemingly wished they'd been born British (their debut album cover emulated the With The Beatles sleeve) promptly took their name from The Yardbirds ditty."

----------------------------

Lord Buckley "The Nazz" -- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rr_21xJ1ugk