Todd Rundgren as a songwriter and performer: The Creator Series #5

His career reflections covering the late sixties onwards

This post covers Todd Rundgren’s post-Nazz career as a songwriter and performer.

It is dedicated to the memory of John, my first paid subscriber who triggered this Todd Rundgren series by asking me to research what happened to The Nazz. I just discovered recently that he passed away on July 11th, three days before I began publishing the series. Prior to that, John had been a very encouraging reader with a deep love and knowledge of music, a lifetime of playing in amateur bands, and a knack for reassuring me about the way I was writing about music. Namaste, John.

Today is our last post in this series about Todd Rundgren. We focus on his post-Nazz career as a songwriter and performer. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from his autobiography, The Individualist.

Tomorrow I’ll put out a post with links to all of the Todd Rundgren pieces for those of you who missed any. A warm welcome to new subscribers.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this series as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing it. If there have been any highlights for you, please let me know in the comments.

Now, on to Todd’s reflections on his career and life as a musician after leaving The Nazz…

The role of a musician

Todd defines three categories of artist you can fall into as a musician:

“There is a hierarchy of approaches to engaging an audience. ‘Entertainer’ is the entry level position, requiring you to simply divert people with whatever it is you’re doing... Next up is ‘performer’, someone who can demonstrate a skill the average person doesn’t possess, such as being able to play the most bass drumbeats in a minute. Rarest of all is the ‘artiste’ whose expression cannot be predicted (even by said artiste) and the valuation of such expression is often impossible to categorize. There is no special glory or shame in any of these forms of presentation. You find your comfort level and usually stay there, although if you want to be assured a living, ‘performer’ is probably the way to go.”

He also points out that the recent elevation of the singer-songwriter defies historical precedent:

“Historically, the division of labor in music has dictated that composers are not often performers and vice versa. Certainly most composers have learned to play an instrument, but the age of the ‘singer-songwriter’ is a relatively recent phenomenon. Used to be the troubadour was the bottom of the musical food chain, a wandering minstrel. Now they are the gold standard of pop music, filling the odea that were formerly reserved for symphonies and operas, yea, selling out stadiums never meant for music.”

It appears to be the case that Todd sussed out the music industry early on and realized that, for an artist, there are two surefire ways to make money — being a producer, where you are guaranteed your payment, and composing songs that generate ongoing royalties. Being in The Nazz and meeting other musicians, I’m guessing he heard the tales of artists and bands having hits and still, inconceivably, having nothing to show for it and even owing the record company money. He calls it as he sees it in these two quotes:

“In the early days of the post-Beatles revolution in music everything was fun, anyone could play along and the whole world egged you on. Then the potential for fortunes to be made opened the door to the lawyers and investment bankers and a meme became an industry.”

“Most musicians do not play for life. If you’ve written a lot of songs that still get played you might ‘retire’ and live off the royalties, but that would be a small percentage of players. Many will stay in the business but essentially get a desk job like A&R or marketing, but that’s probably a minority as well. That means that a whole bunch of players have had to find other jobs after spending their entire lives learning to do one thing.”

His own relationship with music

The chasing after fame and fortune as an artist does not appear to be the primary motivating factor in his music career. Instead, it appears that, by becoming a producer of other people’s popular works, he gave himself the freedom to follow his own artistic impulses wherever they might lead and to keep returning to that creative well and engaging in that addictive and fascinating creative process:

“I realized my albums were becoming manifestos of a kind, that the only thing off-limits was convention. Through my constant production work I had become free of the economic pressures most artists felt when in the studio. My singular challenge was not to repeat myself, something that my peers were nearly obligated to do if they were going to hang onto the attention of a flighty and fickle audience that simultaneously considered change a kind of treason.”

“… that which lured me to music — creating something from nothing.”

“The only class I ever truly loved in school was chorus, odd because I wasn’t really that into vocalists at the time. I liked singing in the choir because nobody could really hear me but myself. The lessons I learned about breathing and pronunciation have been ingrained in me ever since. And what I thought was a very simple instrument turned into a lifelong fascination, something that, no matter how much I use it or think I know about it, keeps evolving.”

“There is music in everything and you just forgot to notice.”

Todd elaborates further in this video (after he explains what happened with The Nazz), emphasizing that having artistic freedom and not being constrained by genres or popular tastes is what has been important to him, and that this has been enabled by the security of his producing career:

Artists do need practical help

Todd admitted that he had no clue how to manage things outside the recording studio or offstage. Albert Grossman got him a manager for both his life and his career, Susan Lee, who helped Todd with buying a house, paying taxes, and, when necessary, bullying promoters and house managers who didn’t do what they had agreed.

Eric Gardner [of Panacea Entertainment] “had been in charge of the massive production that was the RA tour” and eventually took on not just tour management but the “other responsibilities a band without a manager needed done.” Todd explains why he thinks his relationship with Eric has worked:

“Because artist/manager relationships can be notoriously fiery and contentious it’s unusual to have a decades-long relationship and I have to conclude that in the case of Eric and me, it’s because we have no written contract. Our relationship could be dissolved at any moment and that has caused us to be very adaptive, he to my whims and I to his focus on the bottom line.”

Being in the music ecosystem

Todd has always been immersed in the music ecosystem, enabling him to continue learning from, and being inspired by, other artists. In New York City he lived near the Fillmore East, the Electric Circus, and Max’s Kansas City, where he hung out and saw acts as diverse as the Wailers, early Steely Dan, and Iggy Pop. He also hung out at ‘Steve Paul’s The Scene’ with house band the McCoys, where he saw emerging acts such as Tiny Tim, the Nice (Keith Emerson’s original trio), Sha Na Na, Alice Cooper, and Duane Allman, and where he himself could jam with others later in the evening. He met Patti Smith at Steve Paul’s flat and through her met Robert Mapplethorpe and other influential artists, designers, and musicians.

While in California, he was pleased to find that “Something/Anything and the radio hits that it spawned opened a lot of doors for me.” He hung out with Wolfman Jack and Brian Wilson, and was greatly influenced by Brian’s prescient understanding of the possibilities of recontextualized music and of the studio itself as an instrument.

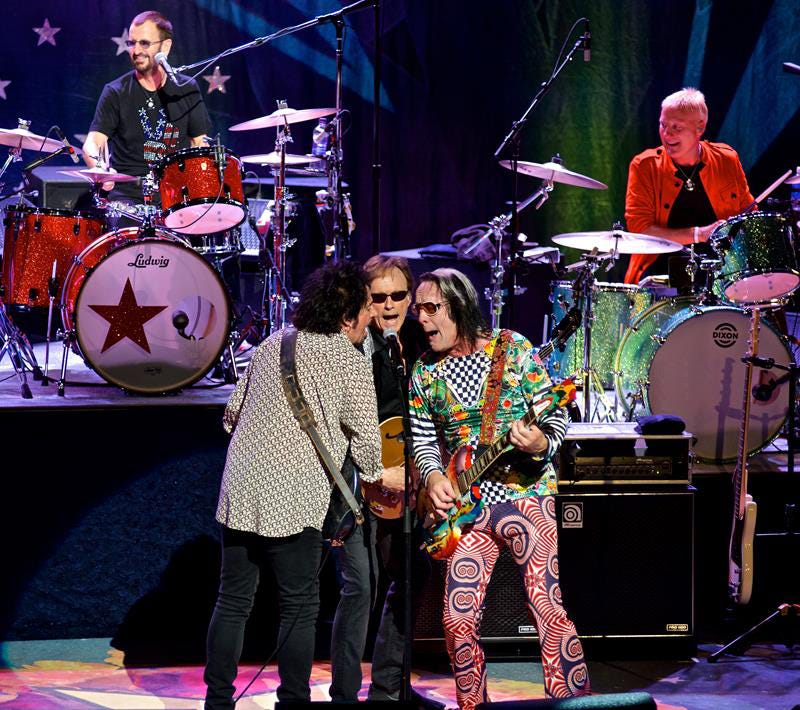

As we know, he’s collaborated and toured with many musicians over the years, including with Daryl Hall in 2022 (as well as being on Live from Daryl’s House twice, in 2009 and 2011), and as a member of Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band for eight years (1992, 1999, 2012–2017), doing vocals and playing a range of instruments, including guitar, harmonica, keyboards, drums, percussion, tambourine, and bass. He was delighted not only to bond with other musicians for three months, but also to pay off what he viewed as his karmic debt to the Beatles, whom he credits with opening up the business for everyone who followed.

He also notes that not all musicians are fun to collaborate with. “Music soothes the savage breast, but it doesn’t necessarily mean the musician is a nice person… You could say that music redeems the savage prick, but that prick better be able to play his ass off.”

On not knowing how to read music

Todd never learned how to read music and makes an argument for why that might be a good thing:

“There is an argument for never learning to read music, that being the resulting inability to play something that isn’t written. There is nothing like the relationship with an instrument that is as fluid as speaking your mind. Now you just have to find something worth saying.”

In case you’re wondering what he does when a song comes into his head and he’s desperate to remember it, a dramatic case of that happened to him in Kathmandu, Nepal. He awoke with a song in his head and, being on holiday, didn’t have any guitar or recording device with him. So he spent half an hour visualizing the keyboard and how he would play it, and he kept doing that for weeks until he got back home and in front of a piano again. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Inspiration for his songs

Todd’s songs up to and including those in Something/Anything? were about what he referred to as his high school crushed love. He talks about it with his signature humor:

“It’s better for me to always believe I was the loser in my first love affair. That conviction forced me to find a discipline in which to express my virgin heartbreak and begin to write actual songs with words and stuff. Otherwise, my musical career might have ended up as a guitar hero who couldn’t keep up with changing tastes and had to become an A&R man at an indie label for big hair bands and unable to have a relationship that wouldn’t be considered abnormal in Bangkok. Shudder.”

After Something/Anything? (1972) with its hits “Hello It’s Me” and “I Saw the Light,” he decided to abandon the pop song as a vehicle for his music because “while the music drew on a somewhat broader range of influences, even that was getting bit formulaic while still being dependent familiar forms.”

As he explains, “Pop music is not about change. The effect of the ideal pop song is to make the listener feel upon the first listen like they have heard it before. This is not the product of calculation or computer programs could write pop hits (maybe they can by now). We are only comfortable listening to certain sounds and structures and culturally inherited modes, so when we write we gravitate toward the familiar, just as we listen. Then there are those rare instances that seem at first unfamiliar, even alien yet they dredge up something deeply primal in everyone who [hears] one.”

In a video interview last year with Noise11.com, he puts paid to the fact that he is ready to retire from songwriting, like some artists, or will ever be ready to do so given the kind of music he composes:

“I guess at a certain point some musicians, they just get tired of it or they run out of ideas or something like that, and they more or less retire from songwriting. I still have lots and lots of ideas and horizons to explore and things like that. I can do that because that’s been historically what I’ve done. I don’t make Top 40 records. I don’t make instant hits. Most of what I do has kind of a slow burn element to it. People often don’t get it until the second time. Sometimes they never get to the second time [laughs]. But the kind of music that I make sort of reveals itself over repeated listenings. It’s not there in just one listening.”

In that same interview he insists that he never writes with the idea or expectation of anyone else doing a cover:

“I write a song for me, for my voice, for what I’m thinking. I never think in terms of other artists covering it. It’s always a pleasant surprise when someone does, but I never think about that when I’m writing. I feel that lets dishonesty creep into the process if you’re suddenly trying to outthink other people rather than just trying to figure out what the hell you mean. You know, what exactly do you mean? That to me is always the biggest challenge. The more songs you write, the harder it becomes because you’ve written so many already. What do I write about now? I’ve written 300 songs. What’s left to write about? But you manage to find something, somehow, and I still get excited about the prospect of writing new material and doing another record. I’ve got ideas. I’ve got a theme. All I have to do is just sit down and do it.”

Songwriting and recording

In his autobiography Todd related some of the highlights from his songwriting and recording process, from Something/Anything? (1972) to New World Order (1993), as well as his short-lived TV scoring work.

For Something/Anything?, he rented an 8-track to record at home. He had gotten into regular pot smoking and saw his inspiration and creativity increase to the point that he was “writing almost constantly, pulling ideas out of the air, tripping over new refrains at every turn. I would wake close to noon, get high, go to the studio (where I couldn’t get too high or else I couldn’t play), come home about 6 or 8 hours later, eat, get high, write and record some more and go to bed… It was the first time I played all the instruments myself so I was full of the challenge of thinking like a drummer or bass player. I had an 8-track machine brought in and would spend the evenings at home perfecting my synthesizer ‘chops’ and doing Les Paul recording tricks and sonic gags a la Spike Jones… The record swelled to a double album whose only concept was prolixity. I pretty much had to force myself to stop.” He also created the album cover, borrowing a camera and light and taking the shot in his living room/studio.

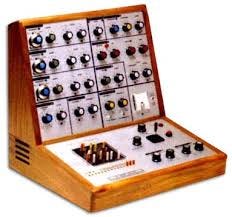

Todd bought the only EMS VCS3 Putney Synthesiser available from Manny’s Music and learned how to make instrument sounds and other noises on it. Pink Floyd’s Dave Gilmour went to Manny’s looking for one and ended up spending an afternoon with Todd seeing what it could do. A love affair between Todd and synthesizers was born. As an early adopter he incorporated the sounds into his music and was labelled ‘futuristic.’

In the video below, Todd shares the intention behind A Wizard, a True Star, the album that followed Something/Anything? the next year:

After A Wizard, a True Star, an expanding number of musicians joined Todd in “whole new vistas of musical tomfoolery.” He returned to writing more traditional songs for the next album, Todd (1974), but tried some unconventional things, like having two different audiences comprise the chorus to “Sons of 1984,” overdubbing the raucous New York City audience on the right side of the mix and the disciplined San Francisco audience on the left side.

The label also made a poster of his face (below) from the names on the 30,000 postcards they had received back from A Wizard, a True Star buyers, who had been promised having their name on Todd graphics, a promotional gag thought up by Albert Grossman. I believe at least two of you (Brad and Hugh) appeared on that poster!

For the album Nearly Human (1989), “I got it into my head that I should start recording live in the studio since everything in pop music seemed overdubbed to death. For a couple months I would write and arrange during the week and call a session at Fantasy Studios on the following Sunday. The routine was pretty much the same for every song — call the rhythm section and teach them the song, then take the singers to another room to learn the backgrounds while the band rehearsed, then run over the charts with the strings and/or horns, then mash it all together sometime by late afternoon. We would do takes until I was sure we had everything covered correctly then take a break whereupon we would get as drunk and high as quickly as possible before capturing the ‘mood altered’ performances that, as it turned out, made up the bulk of the final album. Ironically, the end result was a boost to my career and garnered the lead review in Rolling Stone. The tours that resulted fulfilled my dream of having a ‘review’, a big band with singers and horns and slick arrangements and we went around the world and slayed wherever we played.”

“If it hadn’t been so expensive to maintain I might have gone on for years with that approach, but my arrangement with Warner Brothers was coming to a close and that meant I had no more record production budgets and no more tour support. I did manage one more crack at a live recording on the following record Second Wind which was recorded at the Palace of Fine Arts [in San Francisco] in front of a live audience, just to add excitement to the performances. I made them pretend they were in church so it would sound like a studio album.”

“Up until No World Order [released in 1993, the first interactive record album in history], I had been pretty anal about what the audience was supposed to experience from my records. It was a revelation to confront the fact that they were looking for a more granular way to absorb media, one that conformed to the new age of portable devices. The likelihood that a listener was going to surrender to my version and how it should be absorbed was becoming undependable and I had to accept that. Now if I could just get the music business on that wavelength. Naïve.”

Todd also wrote a few TV music scores in 1986, starting with a crime show, Michael Mann’s Crime Story. He wrote “elaborate evolving themes,” and when the show aired was disappointed to find the same eight bars repeated over and over. He then moved on to Pee Wee’s Playhouse, where he had the opposite experience. He found it fun and they didn’t meddle and used everything he came up with (for episodes 11 and 13 of Season One). Thinking that it could never be that easy or fun again, he lost interest in scoring, but also realized that he didn’t have the temperament for it, having to work to a fast deadline and knowing that much of what he wrote might not even get used.

Stagecraft and performing

There were also a number of interesting highlights from touring and performing that he recounted in his autobiography.

Todd decided in 1973 that he wanted to set up a space-age concept band called Utopia that would be “super theatrical and have custom matching ‘space suits’ and instruments.” Each musician would have different-colored hair (for example, Dave Mason came on board as a keyboard player and had an orange and purple dye job), and they would have cool things on tour, like surround sound and a lunar module onstage. The elaborate show worked once and Todd pulled the plug because it was bleeding money. He notes that everything was pass-fail back then, and now it would be considered a beta version with flaws that could be fixed.

Later in 1973, after completing a live recording and some other projects, Todd decided to revive Utopia with a new line-up. His songwriting had migrated to the piano and he wanted to keep up his guitar chops. He and the reconstituted band were into prog rock and influenced by Mahavishnu Orchestra, “composing long polymodal polyrhythmic marathons with bits of vocal and occasionally something that sounded like a song.” After the first record [Todd Rundgren’s Utopia, 1974], they did four to five-hour shows. For the second record [Another Live, 1975] they did the album live, with Luther Vandross as one of their backup singers.

He explains the positive effect working with Utopia had on his guitar playing:

“In Woody’s Truck Stop and The Nazz I was not required to keep up with musicians of the caliber that comprised Utopia. We were comparing ourselves individually to our various heroes as well as to each other and I developed a whole new relationship with the guitar. The material was structured in a way that left long passages without vocals and an uninterrupted focus on the instrument. For fleeting moments I could channel the inner mounting flame.”

Things worked swimmingly with the Utopia album and tour called Ra (1977), which had a neo-Egyptian theme. The stage included a 25-foot-tall pyramid of gold-painted steel pipe, a 12-foot sphinx with a laser from its forehead and smoke from its nose and paws, and a moat with dancing water jets surrounding the drum riser. For their big production number, they each had a battle with either earth, wind, fire or water, with Todd scaling the mountain (earth) and doing a forward flip while noodling his guitar. It was apparently an unforgettable show. (Did any of you see it?)

Jumping forward sixteen years to 1993, Todd recounted the opposite experience, how he “had constant nightmares while mounting the [No World Order] show. There was as much detail between the video and lights and computers all talking to each other that my mind never gave up trying to balance everything on the head of a pin and that would have been enough to disrupt my sleep. But compound that with the fact that I had never performed anything like this before and I achieve a level of anxiety that lasted literally years after that tour left the road.”

Todd continues to do extensive touring in support of his music. He estimated that in 2022 he was on the road nine to ten months, with significantly bigger audiences. He views his audiences as comprised of three different segments — the people who come for his pop hits, the Utopia fans, and the big band musical enthusiasts (e.g., Nearly Human fans).

Some parting advice

We’ll end the series with some advice from Todd on holding your ground in pursuing your unique creative vision:

“…most people, if they have a calling, will likely not realize what it is. Conformity is still the foundation of most societies and if your calling takes you too far out of the mainstream you are on shaky territory and nothing is guaranteed. But if you can succeed at it you’ll find that many have tried and failed to survive on that barren plain and if you do survive you represent their hopes. Your calling is to hold that ground. You are the individualist.”

And a final musical treat from Todd

To end on a high note, here’s a rip-roarin’ song and a video that makes the recording process look like so much fun — “The Want of a Nail” from the Almost Human album, with the great Bobby Womack:

"Want Of A Nail" is a brilliant R&B recording- Rundgren and Womack were ideally matched.

Rundgren is one of the few producers to have issued a compilation of his career, in the form of the CD "An Elpee's Worth Of Productions".

Ellen, I've had very little exposure to Todd Rundgren (my loss), though my first long term girlfriend (Michele) idolized him (one rung down from Linda Ronstadt, who she considered family). Her love affair with T.R. probably emerged as a bit of defiance on my part, and I would surely pay a penance. We could say if we don't like what's on the cover, well, there's always a flip side. Lessons learned.