This is our fourth day focused on women singer-songwriters of the sixties and seventies.

We’ve already covered Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain” and Judy Collins’ “Both Sides Now” and Joni Mitchell’s “Help Me.”

Today we focus on the “barefoot Madonna” who’s been our Queen of Folk for more than six decades, the exceptional Joan Baez.

I’m a day late because, first, I wanted to watch the documentary Joan Baez: I Am a Noise (2023) to get the story from her point of view, and second, I wanted to research a range of perspectives given that the other party involved is the revered Bob Dylan, who’s renowned for creating public relations smoke and mirrors.

Let’s also admit that there is an omerta — a strict code of loyalty and silence, and a refusal to answer questions or provide evidence — among rock dudes. The Mafia have nothing on these guys in the “I didn’t see nuthin’” department. This omerta complicates my job researching and telling the story as said rock dudes are willing to tell all about everyone except their rock ’n’ roll compatriots. So I’ve done my best to provide a fair representation of the parties involved in the face of this “wall of silence” and given the information to which I had access. Hope it’s fair enough.

Song of the day

It’s an observable fact that some of the best songs come from unrelieved heartache with a fine coating of outrage, and Joan Baez’s “Diamonds and Rust,” I would contend, is one such song.

When Joan first saw the relatively unknown Bob Dylan perform at Gerde’s Folk City in New York City in April 1961, she was “transfixed” by this “tattered little shamble of a human being up there just spouting out these words.” She encountered him again at a party where he was mesmerizing everyone with a song he’d just completed, “Hard Rain.”

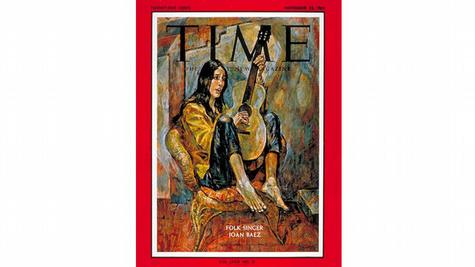

By that time, Joan had already become a folk singing sensation after performing at the Newport Folk Festival in 1959 and instigating a signing battle among a number of record labels. Her debut album was released on Vanguard the following year and would soon go gold with the issue of a second album that reached #13 on the Billboard album chart and got nominated for a Grammy. Joan had also become the female equivalent of Elvis or, anon, the Beatles, besieged by avid fans, in this case male, wanting an autograph — or more. She even appeared on the cover of Time magazine in November 1962.

She was already a star, he a constellation yet to find and settle into its preordained orbit.

One encounter with Dylan led to another. She invited him onstage to perform a duet of one of his songs, “With God on Our Side,” at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963. She then proceeded to bring him along to a string of her own concerts and invite him to join her onstage to sing a few of his compositions, pleading with the audience to listen to him when they booed this unknown and upstart “kid” taking away their precious time with her.

Although “it was a big deal for Bobby,” it wasn’t the case that he was reaping all of the benefits. Joan was heavily involved in the civil rights movement, having become a friend and collaborator of Martin Luther King Jr., and had unmet musical needs of her own. “The obvious thing was music and politics for me and I didn’t have the songs for it at that point. And that was one of the glories of Dylan showing up.”

In retrospect, she came to understand that she and Dylan had fulfilled one another’s psychic needs at that particular time as well, because he needed “a mother. He needed somebody to give him a bath. Somebody to sing his songs. And I needed to mother somebody. I needed to hang out. I needed intrigue. I needed his music.”

She also found that he eased the anxiety and panic attacks that had been her unwelcome companion from well before her singing career. The two of them “had a wonderful time together… a pretty short time that we were really kids together… He was writing an insane amount of stuff… and I was just there writing away with him.”

Life was good, the romance seemingly intact, until Joan joined Bobby on his UK tour in April 1965 and everything fell apart.

Joan was anticipating the London trip as “a huge wingding Beatlerama” in which she might do a concert or television appearance, but really would be there to support and hang out with Bobby. Instead, it turned out, for her, a “total demoralization” and “a nightmare” in which she didn’t fit in as this “weird little folkie” around the newly famous Dylan who was being idolized and mobbed. The drugs and the rock ’n’ roll boys’ club were now in place as well — girlfriends not welcome — and Bobby told the media that he and Joan were “just friends” and that he had “no special one.”

Fast forward to November, and the 24-year-old Dylan got married in a secret ceremony to Sara Lownds, a friend of his manager Albert Grossman’s new wife, Sally Buehler, and a woman he’d been seeing for over a year. She would give him five kids (one from a previous marriage and four together) — and a $36 million divorce settlement twelve years later. Our young troubadour may not have made the wisest financial choice, but it was from all indications a love match whose disintegration would inspire his commercially and critically successful Blood on the Tracks.

Looking back, Joan believes that “Dylan broke my heart because it was so shattering, and it having been such a huge thing… the music issues, the politics, the closeness when we had it.” But she also realizes that “My mental state, anything would have been doomed. Anything. No matter how great that person was… there’s no way that I could have been intimate on a long-term basis, and I didn’t know that yet.” She acknowledges now that she’s “not very good at one-on-one relationships… but great with one on two thousand.”

What she appears to be to this psychologist (me), based on the onset and severity of her symptoms as described in the documentary, is someone who has suffered long-term effects from childhood or adolescent trauma of some sort. She and her sister Mimi reached the conclusion that they were victims of their father’s incest, and as we know this can have lifelong effects. The two of them did confront him while he was still alive and he denied it, suggesting that it was therapist-induced false memory syndrome.

Wherever the truth lies, the good news is that Joan refused to remain a victim and channeled her feelings into her music, writing the exquisite song “Diamonds and Rust” about her relationship with Bobby and producing “possibly the best album I’ve ever done… really put me back on the music map in the industry, made me a lot of money and got a lot of attention.” It was the best-selling album of her career and the title track turned out to be her second top-ten hit.

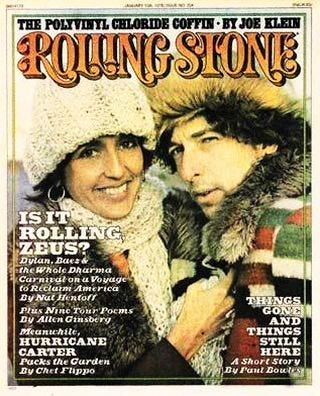

She would also go on to repair and restore her relationship with Bobby, traveling with him on his “fun” 1975-76 Rolling Thunder Revue (see the Rolling Stone cover from January 15, 1976 below), performing on his one-hour TV special Hard Rain, and touring with him and Carlos Santana in 1984. A painting of Bobby hangs over her piano. There is no question that Bob Dylan has been a seminal figure in her life.

Today, as the documentary shows in spades, the 83-year-old Joan is in great shape and continues to nurture her incredible voice. Let’s listen to her song about Bobby — and celebrate how heartbreak and outrage can be transformed into a gift that keeps on giving for the artist, as well as for us, her legions of enchanted fans:

Song credits

Songwriter - Joan Baez

Producers - David Kershenbaum and Joan Baez

Musicians for the album - not all may be on this particular song:

Joan Baez – vocals, acoustic guitar, Moog and ARP synthesisers, arranger

Larry Carlton – electric guitar, acoustic guitar, arranger

Dean Parks – electric guitar, acoustic guitar

Wilton Felder – bass

Reinie Press – bass

Jim Gordon – drums

Larry Knechtel – acoustic piano

Joe Sample – electric piano, Hammond organ

David Paich – acoustic piano, electric harpsichord

Red Rhodes – pedal steel guitar

Malcolm Cecil – Moog and ARP synthesisers, synthesizer programming

Robert Margouleff - synthesizer programming

Tom Scott – flute, saxophone, arranger

Jim Horn – saxophone

Ollie Mitchell – trumpet

Buck Monari – trumpet

Jesse Ehrlich - cello

Carl LaMagna, James Getzoff, Ray Kelley, Robert Konrad, Robert Ostrowsky, Ronald Folsom, Sidney Sharp, Tibor Zelig, William Hymanson, William Kurasch - violin

Isabelle Daskoff - viola

Technical:

Bernard Gelb - executive producer

Rick Ruggeri – engineer

Ellis Sorkin – assistant engineer

I grew up on the sound of Joan Baez (and Judy Collins). By the time "Diamonds and Rust" came out, I was more focused on jazz and fusion, but I bought the album anyway. I still have it. Ironically, the title song didn't make much of an impression on me, but I was glad to learn more of the backstory from your piece, so thank you!. Did you know that the most famous cover of the song is by the Ur-Metal band Judas Priest? It became a staple of their performances and Joan said she was impressed.

Ellen, you might be aware of this story already, but it bears repeating: Joan Baez was an anti-war activist during the Vietnam era, her iconic Martin guitar travelled with her and features in everything she's ever done. Since requiring frequent maintenance, that was done by a host of different professional luthiers. One such luthier, long after the war, brought to her attention an inscription neatly written on the underside of the instrument's top (in reverse, since work performed inside a guitar must be done with a mirror). When this luthier trained his mirror on the inscription, Joan read "Joan Baez is a Fascist Bitch". She reportedly laughed, and declined having the inscription removed. It is there still.