Welcome, everyone, to one of our final posts in the protest song series.

Our focus today is whether artists pay any sort of price for writing, recording, and performing protest songs.

Can it harm their reputation, career, income, or legacy?

One of the examples I’m going to give is quite unflattering to several of the individuals involved. That example will therefore go out in a separate post to paid subscribers and remain behind a paywall.

Going forward I will continue doing this as I delve into more difficult topics and issues surrounding the experiences of women in rock ’n’ roll, such as drugs, sexism, groupies, and record company shenanigans.

One of the reasons is that these topics can be traumatic for some and readers should choose to engage with them. Another is that I want to keep the public posts upbeat and wholly supportive of the music-making community (which exposing the industry’s underbelly does not do).

If you’re interested in delving into the darker side of rock ’n’ roll with me (in which I will explicitly bring to bear my background in psychology and business), you may wish to upgrade to a paid membership.

In case you haven’t noticed, I’ve listed the rock ’n’ roll artists we lost in the first half of January in this post on one of my new substacks, Artist Healing & Gratitude Circle. We lost some wonderful artists recently, and more in the past few days who will appear in the next post.

If you’re interested in upping your wellbeing this year, I’m already underway with my weekly wellbeing experiments, having done clutter clearing last week with highly gratifying results, and this week focusing on self-applied massage. (No, not that kind. We’re not rockin’ and rollin’ over on that site.)

OK, on to the main event.

The cost of protest songs

Can a protest song harm a rock ’n’ roll artist’s or band’s reputation, career, income, or legacy?

The short answer is yes, as we’ll see in some examples taken from the songs I profiled in this series and a few others not previously covered.

The long answer is more nuanced. It all depends.

A free pass to Protestland

We have to take genre into account, as some genres and sub-genres are defined by their stance in opposition to, or at least critical of, the values, beliefs, policies, and actions of what we referred to in the sixties as ‘The Establishment.’

Artists in these categories get a free pass to protest, without repercussions, because that’s what we expect musicians of their ilk to do.

Working-class folk music and punk rock are two such categories.

So, of course, we don’t bat an eyelash when folk singer Joan Baez decides to do a cover of Robbie Robertson and The Band’s anti-war song “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”

We don’t even bat an eyelash that she’s singing from a man named Virgil’s point of view during the last days of the Civil War, because she’s putting herself in Virgil’s place and lending her credentials as a political, social, and civil rights activist in helping us empathize with the plight of a man who’s lost everything in a war.

Embroiled as we were in the Vietnam War when the song came out in 1971, we pushed the single to the top of the charts and made it #20 for the year (and the album #11).

Likewise, we grinned and rushed to get our copies when the Sex Pistols put out a song that equated the British monarchy with facism and accused it of destroying the dreams and prospects of the working class. We gleefully sent “God Save the Queen” to the very top of the singles chart in the UK at the very same time as the celebration of Her Majesty’s Silver Jubilee.

Those Sex Pistols. They’re punk rockers, so what else would we expect but outrageous cheekiness toward the powers-that-be in a protest song wrapper?

On the other hand, we don’t expect straight-up protest songs in pop or even many sub-genres of rock.

From what I’ve seen, artists use at least two strategies to put out a protest song without getting themselves in trouble for doing so.

One is to hide that protest song in plain sight, and the other is to outright deny that it’s a protest song.

Hold on, this ain’t sweet cherry wine

If you’re an artist or a band and you want to protest, but you don’t want to get any blowback for it from your label or fans, easy-peasy. Just disguise it as one of your regular songs.

Probably the most brilliant example of this is “Sweet Cherry Wine” by Tommy James and the Shondells, which disguises a protest song with an upbeat melody and syrupy sweet lyrics except for a single verse that slips in an anti-war message.

At the time it came out in 1969, I thought it was a song selling us kids on a delicious alcoholic beverage, when the band was actually singing about the blood of Christ and taking a stance in favor of pacifism.

Not what we would expect from a group with hits like “Hanky Panky,” “Crimson and Clover,” and “I Think We’re Alone Now.” But then, as I covered in my post on the song, the group did have to make sure they churned out hits to keep their Mafia-owned record company happy, something that caused Tommy no insignifant amount of anxiety.

This strategy of hiding a protest song in plain sight works because most people don’t listen closely to the words anyway, and even when they do, they often can’t figure out what the artist is singing and don’t have the time or energy to look up the lyrics.

As I wrote in a substack comment recently, I always thought that ELO was singing “Don’t bring me down, Bruce” and wondered who Bruce was. Likewise, I thought the Four Seasons were singing to someone named Sitorgia and wondered who she was and why her parents gave her that ‘out there’ name. (“My eyes adored you” were the actual words.)

Mishearings of lyrics are rife among music consumers, and they’re often crazy and hilarious, as this Stacker collection of 60 of them abundantly shows.

Those who make the effort to check the lyrics are a rarified bunch. Apparently they do so to “confirm what the artist sings, more deeply understand the lyrics, sing the song, and figure out the structure such as verse and chorus.”1

In other words, they tend to be other musicians, music writers and aficionados, and, I would suggest, people whose brains prefer to process songs through the lyrics.

For those of you intrigued by brain research, processing of music by the brain has been found to be different for melodies and lyrics.

So is it any surprise that some people are grabbed by melodies and wouldn’t dare attempt karaoke without a teleprompter telling them what to sing, whereas other people know every single syllable and every vocalization by the artist in every single one of their favorite songs?

Back to Tommy James and the Shondells, who had a good reason to hide their protest song in plain sight. As I alluded to, they didn’t want to end up in a pair of concrete shoes.

But more importantly, they might just succeed in influencing you and other listeners through subliminal programming, by slipping the ideas into your unconscious without your even realizing that it’s happening, starting with that opening that sounds like a church service, the invocation “Oh, Lord,” and the metaphor of the sweet cherry wine “so very fine” that “he gave us.”

Tommy and his bandmates had become Christians, and they were spreading the Gospel and a message of peace — not war — through their song.

If you want another example loaded with messages in both the words and the images, watch — and outright marvel at — “Sun City” below. These musicians are not holding back in finding every means possible to get their message across directly as well as subliminally. Make no mistake that successful artists traffic in powerful symbols and metaphors and are ruthless in their use. Case in point.

Could you find a more powerful and legitimate symbol of apartheid for a musician to denounce than a gambling and entertainment complex named “Sun City” that exploits a captive and beaten-down workforce?

Katniss Everdeen didn’t need a bow and arrow to fight the oppressors of Panem. She needed a band of outraged musicians!

Deny is a four-letter word

There’s another strategem artists use to put out a protest song without alienating listeners and losing hard-earned fans.

Deny that it’s a protest song.

In explaining “Masters of War,” Bob Dylan said that it’s “supposed to be a pacifistic song against war. It's not an anti-war song. It’s speaking against what Eisenhower was calling a military-industrial complex as he was making his exit from the presidency. That spirit was in the air, and I picked it up.”2

Say what, Bob? A song against war is not an anti-war song?

Is he saying that he’s channeling a pacifist view, which is by definition anti-war, but… Hmmm. I’m confused.

Didn’t you tell the masters of war in the final verse that you hoped they would die, Bob, and soon?

Likewise, Obie Benson peddled a song to his fellow Four Tops at Motown and got turned down because “my partners told me it was a protest song… I said, ‘no man, it’s a love song, about love and understanding. I’m not protesting, I want to know what’s going on.’”3

Of course, the song was “What’s Going On,” and the commercially successful Four Tops weren’t about to alienate their audience expecting their usual catchy and soulful tunes by releasing an out-of-place ‘downer’ protest song.

Obie had written it after witnessing police brutality against anti-war protesters and the killing of an innocent bystander at People’s Park in San Francisco in May 1969, a day referred to as Bloody Thursday.

C’mon, Obie, you know it’s a protest song, man.

That’s exactly why it appealed to Marvin Gaye, who was reeling from the stories his brother had told him after returning from the Vietnam War. Marvin ended up recording the song and making it his own, as the lead track on an entire album devoted to protest songs. A protest album that’s ranked as one of the greatest albums of all time.

But then Marvin was no longer concerned about the audience. He was concerned about expressing himself, influencing people, and leaving the artistic legacy he wanted to leave. That four-letter word starting with ‘d’ wasn’t in his vocabulary at that time.

Fellow Motown singer Edwin Starr followed in Obie’s steps and also denied that “War” was an anti-war song. Say what, Edwin?

“The misunderstanding about the song ‘War’ is that the song was never supposed to be about the Vietnam War. What they were simply writing about, was about the conflicts that people were facing on a day-to-day basis in the United States at the same time with all the riots and things.”4

As I mentioned in my post about this song, it’s hard to buy Edwin’s interpretation when you look at lyrics like “War means tears to thousands of mother's eyes When their sons go off to fight And lose their lives,” as well as “induction then destruction, who wants to die? Oh.” Induction at that time was a clear reference to conscription of young men into the military.

Why would Bob, Obie, and Edwin all deny that their songs are anti-war using mystifying and over-the-top verbal acrobatics? What are they worried about?

Losing their reputation and their audience, of course. A legitimate concern, underscored ad nauseum by the record companies tracking the bottom line.

Let’s look at the case of “War” more closely.

Kaboom! and bye-bye career

Like Marvin, Edwin Starr was frustrated with his career at Motown.

He’d been happy as a songwriter, producer, and singer at his previous label. But then disaster struck when Motown bought that company, Golden World Records, and with it his contract, all because Motown head Berry Gordy wanted to get control of one of Edwin’s songs, “Oh How Happy,” to use as the theme music for a Jackson 5 cartoon series.

You can’t make this stuff up!

At Motown, the hit-producing Edwin found himself sidelined as a songwriter and producer and underutilized as a singer. Motown wanted his song, but the fact of the matter was that they didn’t know what to do with him.

That is, until he forged a relationship with legendary Motown producer and songwriter Norman Whitfield and put out a string of love songs with him, which proved to be a stroke of luck.

By the late sixties Norman, like Marvin Gaye, was growing impatient with the company’s conservative approach to music-making. He knew, from frequenting the clubs, that popular music was capturing and reflecting the disenchantment of youth with the Establishment and their demands to end the war.

He co-wrote the protest song “War” with his regular songwriting partner, Barrett Strong, and convinced the company to let him record it with the Temptations for their Psychedelic Shack album.

But when thousands of college students wrote in asking for it to be released as a single, the company balked. According to Edwin Starr, the company considered the song “political dynamite” and refused to sanction the release of a single that might alienate the group’s more politically conservative fans.

The Temptations could go ahead with the politically ambiguous “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World is Today),” but a less commercially important artist would have to re-record “War” if Barrett insisted on issuing a single and catering to all those persnickety college students.

When approached to do the song, Edwin already knew the subtext. The company considered him expendable. If anyone was going to protect his reputation and his career, it would have to be him.

So he told Barrett he would do it on one condition. “As long as they understand that I will stay true to who I am. I will not alienate what it is that I do. I sing funk and soul, and that’s what I do.”

It might be political dynamite, but in Edwin’s hands (and voice) it was going to be political dynamite like no other.

Barrett agreed and let Edwin off the leash. As I wrote in my post about this song, a significant factor in its success was “the personal commentary that Edwin added to [it]: ‘“Good God y’all’ and all those ‘Absolutely nothings’ are my ad-libs.’ His additions grabbed attention and made it one of those songs you had to sing along to.”

With little to no promotion by Motown, the song raced to the tops of the charts and perched there, eventually going double platinum and in the process becoming an anti-war anthem.

Edwin made his peace with the song as well, especially with the validation that came from earning a Grammy nomination.

As you can see from his appearance on the Midnight Special in early 1974, not only was he no longer denying that it was a protest song, he was actively embracing it by having his musicians pretend to die onstage during the song and ending with an anti-war message.

I’ve never seen anything like this. All I can say is, it was the seventies.

Letting loose a cannibal

Whereas Edwin Starr proved himself remarkably adept in preventing a protest song from blowing up his career and ruining his reputation, Crosby Stills Nash & Young proved unwilling to prevent one from cannibalizing one of their hit songs and losing them a not-insignificant amount of income.

They knew it was going to happen, and they went ahead with the protest song anyway.

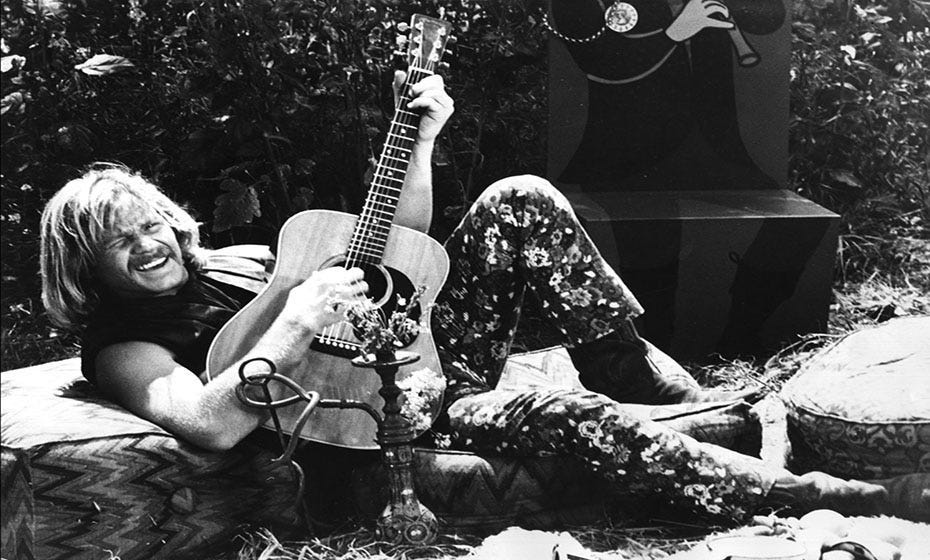

In the spring of 1970, David Crosby and Neil Young of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were hanging out in Butano Canyon in northern California when they got the news about the shooting of four students at Kent State University.

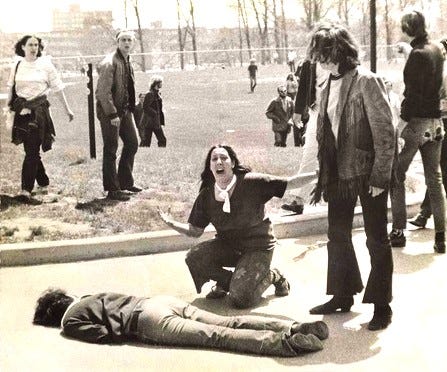

Although Graham Nash believed that his bandmates had watched it on the news (as reported in my previous post), David’s recollection was of opening Life magazine and seeing the horrifying picture of a girl, Mary Ann Vecchio, kneeling next to slain student Jeffrey Miller “with a ‘Why?’ look on her face.”5

He handed the magazine to Neil, and after observing the shock register on his face, handed him a guitar. David watched and provided singing accompaniment as his bandmate and friend, the photo in front of him, poured his feelings into a song of protest that came to be called “Ohio.”

Perhaps close to what David heard that day up in Butano Canyon is this raw, unaccompanied acoustic version of the song as Neil Young performed it just eight months later.6

If you were David Crosby and had witnessed and assisted in the birth of this protest song, what would you do once it arrived perfectly formed and squalling for attention?

I don’t know about you, but I think I would have reacted the same way David did. He wanted everyone to see and hear it. Right now.

He called Stephen Stills in L.A. and got him to book a studio for the very next night.

The band went in and recorded “Ohio,” laid down another protest song for the B side, Stephen’s “Find the Cost of Freedom,” and handed the masters to the president of their record company, Ahmet Ertugun, who was leaving on a red-eye to New York.

They were lucky because Ahmet well-understood that topical songs related to politics, movements, and current events have windows of opportunity and expiration dates.

After all, Ahmet had handled Buffalo Springfield’s protest song “For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound)” following the curfew riots on Sunset Strip, rushing it out to capitalize on the zeitgeist. The song had reached #7 on the Billboard Hot 100.

So Ahmet acquiesced in doing the same with this one, getting the record pressed and distributed to radio stations within a mere ten days.

But, as I wrote in my post about “Ohio,” both Ahmet and the band realized that there would be a price to be paid for rushing this protest song out.

“At the time we had ‘Teach Your Children’ halfway up the charts as a hit,” David noted, “and Nash said to pull it and release ‘Ohio’ instead. And they did. It was immediate, it was direct; it was, ‘Nixon, this is you. We’re pointing the finger at you, asshole.’”7

Graham Nash concurred that “We killed our own single of ‘Teach Your Children,’ which is my song, and we didn’t care. We didn’t care about any of those rules. We didn’t care about the record company saying, ‘Listen, you don’t want to do this. Let “Teach Your Children” get up there, do its thing, and then, you know, a couple of months later bring it out.’ What we wanted to do was bring it out instantly now. We were angry now. The kids were angry now. We wanted to speak and scream about this now. We wanted to put that record out on top of our other record, and we killed it stone dead, and we didn’t care.”8

They deliberately killed another one of their songs already climbing the charts “stone dead.”

I think we can understand their decision when we listen to “Ohio,” a song that still gets to me to this day. Don Henley of the Eagles summed it up beautifully when he recalled hearing it for the first time on the radio. “It made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. It had what I would describe as a terrible beauty to it.”

The song reached #14 on the Billboard Hot 100. (“Teach Your Children” reached #16.)

I’ll end with David’s final words about the song that indicate why a band like Crosby Stills Nash & Young might be willing to sacrifice significant record sales income to put out a protest song whose success is nowhere near assured.

“‘Ohio’ got a huge amount of airplay. Even today [in 2000, 30 years later], people still connect to it deeply. In the best tradition of troubadours, we put the truth out there and it worked. It remains one of the proudest moments of my life.”9

Next up

For paid subscribers, we’ll delve into the unsettling example of an artist losing their shot at a rock ’n’ roll career and legacy as the direct result of a protest song.

For free and paid subscribers, we’ll be wrapping up this series by asking some key questions, namely What is a protest song? Can we even define it? How will I know it when I hear it?.

“Toward an understanding of lyrics-viewing behavior while listening to music on a smartphone.” Kosetsu Tsukuda, Masahiro Hamasaki, and Masataka Goto. Proceedings of the 22nd ISMIR Conference, Online, November 7-12, 2021.

Gundersen, Edna (2001-09-10). "Dylan is positively on top of his game". USAToday. Retrieved 2011-01-27. (Retrieved from Wikipedia, August 26, 2024.)

Lynskey, Dorian (2011). 33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day. HarperCollins. As quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What's_Going_On_(song)#cite_note-FOOTNOTELynskey2011155-8.

Stand Up and Be Counted: Making Music, Making History. David Crosby and David Bender. HarperCollins, 2000.

From Live at Massey Hall 1971, released in 2007.

See footnote 3.

Transcript of

See footnote 5.

'War can't give life/It can only take it away." Messrs. Whitfield and Strong at their finest, with Edwin Starr delivering a fire-and-brimstone preacher tone to make it all work. Masterful.

Excellent piece, as always. And holy moly, that Edwin Starr clip is *amazing*! Never seen that one before, thanks for posting it -