How three artists — Peter Gabriel, Stevie Wonder, and Little Steven — helped bring down apartheid and inspired others

The protest song series

Welcome, everyone, to another post in the protest song series.

Today’s post is an incredible story about how three protest songs helped to mobilize action toward ending apartheid in South Africa.

Because it’s a long post, I’m not including my usual list of previous posts in the series. You can find the latest list at the beginning of “Favorite protest songs of devastating beauty and power.”

Full disclosure, I didn’t remember any of the songs profiled in this post, the song by Little Steven only coming to my attention when Amy McGrath chose it for inclusion in a collection I published called “Favorite protest songs of other Substack writers passionate about music.”

Then, in that mischievous manner in which the God of Synchronicity enjoys playing with us, the story behind Little Steven’s song came to me in two different ways and demanded my attention with its outrageousness and brilliance.

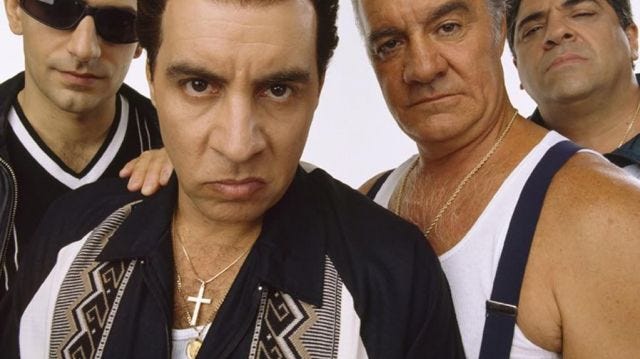

First was reading somewhere that I must watch the documentary Stevie Van Zandt: Disciple, which I did even though I didn’t know much about him beyond being a fan of his character, Silvio Dante, in The Sopranos (below).

And second was discovering a copy of David Crosby and David Bender’s book Stand and Be Counted: Making Music, Making History - The Dramatic Story of the Artists and Events that Changed America in a used bookstore, devouring the entire thing on New Year’s Day, and concluding “I have to tell the apartheid story.”

Before we delve into it, let me just say that Crosby and Bender’s book throws out any argument that protest songs don’t have impact. The authors provide example after example of significant impact in chapters devoted to the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement, benefit concerts, political activism, the antinuclear crusade, global activism, lending a hand through activities like Farm Aid, and human rights.

If you need major convincing, get that book.

But in my view, the story you will read below is compelling and indisputable proof. Protest songs can, indeed, have profound and lasting impact, both in terms of changing the world and also in inspiring generations to come, musicians and listeners alike, to believe in and work towards bringing about meaningful positive change.

Please note that I will be using a lot of quotes in this post, because words are powerful, and they are also subject to misinterpretation. The artists involved are articulate and passionate, which is an important element of this story. The quotes are taken willy-nilly (without footnoting) from the sources listed at the end.

OK, hold on to your hat because you’re in for a wild ride today. Ready?

Peter reacts to the murder of an activist

In South Africa under the apartheid regime, black citizens could not vote, own land, or get married to someone from another city. Unlike whites who had full rights and freedoms under the law, blacks were not allowed to do just about anything without government permission.

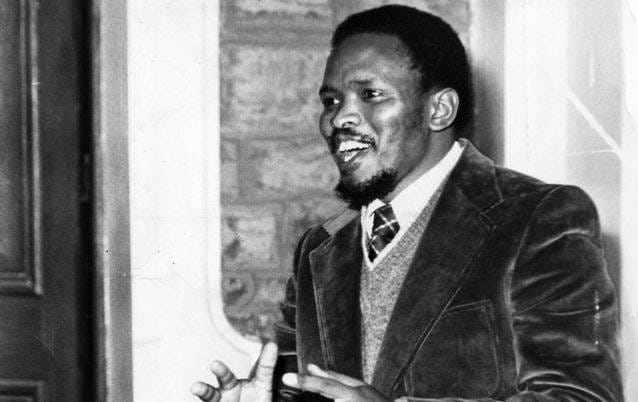

In August 1977, South African anti-apartheid activist Steven Biko was arrested for violating a banning order that prohibited him from leaving his district, speaking to more than one person at a time (to prevent public speaking), and belonging to a political organization. The media was also prohibited from quoting him.

While in custody, Biko was interrogated by ten security police officers for 22 hours and severely beaten. At the behest of doctors, he was eventually transported, naked and manacled, to a prison hospital 740 miles away, where he died from the brain injuries (as well as acute kidney failure) that the security forces had inflicted upon this formerly healthy 30-year-old man.

According to Peter Gabriel, many were following the anti-apartheid movement in the newspapers and on TV and believed that “there was enough publicity to ensure nothing would happen to [Biko]. So I think there was a real sense of shock when we learned of his death.”

In fact, at least 45 other political detainees had died during interrogation since 1963, when the laws had been changed by the government to allow imprisonment without trial, and 20 people had died in South African prisons in the preceding twelve months.

Peter suspected that the South African authorities meant to “torture the hell out of him” but not kill him. On Sunday about two weeks after his death, twenty thousand black South Africans gathered to mourn Steven Biko.

At that time Peter, like many, was already aware of and revolted by the racism enshrined in South Africa’s constitution, but he wasn’t actively involved in any political movements. The activist’s brutal murder spurred him to write and record his very first political song, “Biko.”

The official video of the song (below) shows footage from the film about Biko called Cry Freedom (1987), directed by Richard Attenborough and starring Denzel Washington as Steve Biko and Kevin Kline as his best friend, journalist Donald Woods.

Please be warned that the song is haunting and the video content is graphic and upsetting. (I can’t watch it without crying.)

Coming out in August 1980, “Biko” made many more people aware of the issue and became an anthem of a burgeoning anti-apartheid movement.

One of those people it made aware was the lead guitarist in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, Steven Van Zandt, known as Miami Steve and Little Steven.1

Little Steven goes all in on South Africa

Touring with the E Street Band on The River Tour in 1980-81, Steven was accosted while walking in a park in Germany by a kid asking, “Why are you putting missiles in my country?”

This pointed question to the staunchly apolitical Steven jolted him, and awakened him to the fact that others had differing perceptions of America, and even more shockingly, that he and his band were viewed not just as musicians but as ambassadors of the United States.

The question would not leave Steven’s head. Literally overnight, politics became his consuming passion. As long-time friend and bandmate Springsteen observed, “Stevie’s an all or nothing person… He’s all in, or he’s not in. And when we first started out, Stevie was no politics… Then he became all politics. It’s all politics.”

That passion was channeled into Steven’s solo work with his new band, Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul, and the release of five albums he characterized as a political concept cycle addressing the individual (“Men without Women”), the family (“Voice of America”), the state (“Freedom — No Compromise”), the economy (“Revolution”), and religion (“Born Again Savage”).

With the second of these, Voice of America (1984), his work became overtly political, including such songs as “Los Desaparecidos” about the Disappeared in South America in the 1970s and 1980s, and “I Am a Patriot”2 about being a patriotic American committed to freedom.

Steven wasn’t expecting his protest music to flip a switch and change the world overnight. “I felt if I could shine a light on some of these things, maybe I could stimulate some thought, which would stimulate some conversation, which would stimulate some action. So, we’re supposed to be the heroes of democracy and freedom, and we weren’t.”

The apartheid situation wasn’t even on his radar. “I didn’t really know what was going on in South Africa. I hear this song ‘Biko’ by a guy named Peter Gabriel. But, man, this song was amazing. It really led to my engagement with activism in general, and specifically the apartheid regime with South Africa.”

Intrigued, Steven read about political reforms in that country, but beyond that “couldn’t find out much about South Africa. It was just very, very mysterious, and I had to see it first-hand.”

In an effort to investigate and discover the truth for himself, on his first trip to South Africa he spent a month meeting with scores of people, including other musicians, anti-apartheid activists, and members of the governing ethnic group, white Afrikaners descended from Dutch colonial settlers.

“Some of my interviews were quite revealing when I realised they were talking about the justification for apartheid… They justified it from the Bible. There was a religious sort of justification for apartheid and I’m like, man, when you start to get into religious justification, it’s getting deep. Now we’re in like way too deep. There ain’t no fixing that there. Religious fanatics, you can’t fix them, you gotta just exterminate them, you know?”

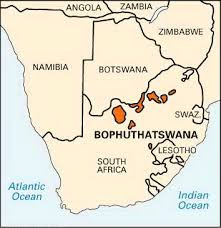

At the time of his visit there was a cultural boycott of South Africa, and the country had gotten around that by setting up what they claimed to be a separate country within South Africa called Bophuthatswana (colored sections below).

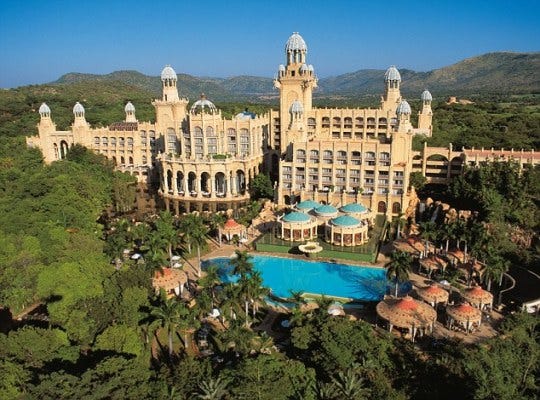

Within that ‘country’ was an entertainment and gambling resort called Sun City (photo below) where South Africa could continue to reap the rewards of tourism using big-name Western entertainers and forcibly relocated black labor.

According to Daryl Hall, even before Hall and Oates had achieved commercial success they were offered “a ridiculous sum of money, like two million dollars, to play there.” (Comparable to about $12 million today.)

“Sun City’s a resort like Las Vegas in the middle of what they call homelands,” Steven explained. “The homelands are where the South African Government is relocating all the South African blacks against their will. So what happens is, they pay a lot of money for [artists] to come down, and every time someone goes down there and plays, they are justifying South Africa’s relocation policy.”

The anti-apartheid activists and musicians he met with on that trip disagreed on many things, but one thing they all agreed on: “‘Please go back and tell the musical community to please not play Sun City.’”

An activist is born

Steven wasn’t yet to committed to any specific action when he returned to South Africa on his second visit.

“I was in a cab and a black guy stepped off the kerb and the cab driver swerved to try and hit him. He [the driver] says, ‘Fucking kaffir’, which of course was the Afrikaans word for [N-word].”

Steven couldn’t believe what he’d just seen and was in shock. “I was like, man, ‘Uh, let me out at the next corner.’ I gotta think about what I just witnessed. And at that moment, really, I went from artist to activist.”

As he later recognized, reflecting on the incident, “At that moment it became more than an intellectual exercise, more than just another subject I was going to write about in my next album… There ain’t no fixing this. There ain’t no reform that’s going to fix this. These guys have got to go.”

Steven realized that he needed to meet with members of the South African liberation movement, which meant finding a way to get into the off-limits homelands where they lived.

“So I’m meeting now with the Azanian People’s Organisation in Soweto [logo above], and had to sneak in the back seat of a car [under a blanket] because there was a military blockade at the time. So they’re burning like coal fires and there’s like three feet of fog as far as the eye could see. And we get to this house, and ‘cat’ comes out.

“They’ve got machetes, and they’re the tough guys. They’re the front lines. They’re blowing up radio stations. They’re killing people. They’re the real thing. And they’re very, very adversarial.

“They don’t like the fact that I’m there. As far as they’re concerned, I’m violating the boycott being there. And, as I explained to them, ‘Look, man, I’m on your side.’ I don’t think they were pretending. I think they were thinking about killing me. But at that point I was completely fearless.”

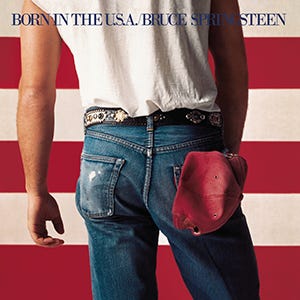

Why was Steven fearless? Because he had quit the E Street Band right before the massive success of Born in the U.S.A., which had seven top 10 singles, went 17x platinum, and launched Springsteen and his band to global superstardom.

“In leaving, I kind of ended my life as I knew it. I mean, what had taken 15 years to get to the top, 15 years, I just walked away from it and had to, you know, begin an entirely new life.”

Although he would reap financial rewards as a producer of the album, he would miss the other-worldly rewards that effortlessly flowed to a band at the pinnacle of the rock world.

Within his grasp had been every rocker’s dream, and he had let it go. Because…

“It had just been me and Bruce all those years. And now a new friend had come into the picture, Jon Landau, who was not only his manager, but he would also co-produce the records. And it was a very, very important sounding board for Bruce.

“So, suddenly… I was a little bit of an odd man out, you know, a little bit, and started to get a little bit awkward, and it was kind of a perfect storm of a lot of elements.

“But I had become obsessed with politics by then and was kind of itching to talk about it… felt it needed to be talked about. We had this grandfatherly, friendly cowboy, [U.S. President] Ronald Reagan, everybody loved, and meanwhile, a whole lot of crimes are being committed in the darkness.

“They were very hidden in those days as opposed to in the previous four years where no crimes were hidden. So I felt a need to talk about some of these things, and at a certain point, I just felt the best way maybe to preserve our friendship is to leave.”

He had left for politics, and now those politics were, literally, staring him in the face and telling him he wasn’t welcome.

“I had lost all of my fear of everything on the flight down to South Africa. It occurred to me that I’d blown my life. Fifteen years of work with the E Street Band and I quit. I just didn’t care about anything at that point.

“So that helped me stand up to them because they were really fingering their machetes as they’re talking to me. I said to them, ‘You’re not going to win this war blowing shit up, OK? And shooting people.’

“And they were like, ‘Oh yeah? We’re not going to win the war that way? How we going to win the war?’

“I said, ‘I’m going to win the war on TV.’

“I got home and started spreading the word. I needed help.”

Is it a Wonder that Stevie got arrested?

At the same time all of this was going on, Stevie Wonder was busy recording his In Square Circle album.

The final cut was a track called “It’s Wrong (Apartheid)” on which he played all the instruments — synthesizers, drums, percussion, and kora — and was backed on vocals by Musa Dludla, Thandeka Ngono-Raasch, Linda Bottoman-Tshabalala, Muntu Myuyana, Lorraine Mahlangu-Richards, Fana Kekana, Tsepo Mokone.

Coming out in September 1985, the album would go double-platinum and spawn two top ten singles, “Part-Time Lover” and “Go Home.”

Stevie would win a Grammy for the album, in the category of Best Male R&B Vocal Performance, and also be arrested for performing “It’s Wrong (Apartheid)” outside the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C.

“They said I was disturbing the peace,” he recalled, “but I was just singing.”

Granted, he was singing words that might be considered provocative, like the opening of the song, “The wretchedness of Satan's wrath, Will come to seize you at last, 'Cause even he frowns upon the deeds you are doing.”

But that’s just an opinion. Promising black South Africans that “Oh, oh, oh, freedom is coming, yeah, yeah, yeah”?

No doubt, Stevie had taken things one step too far.

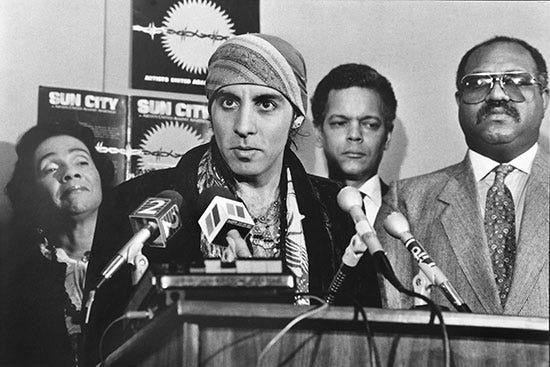

The making of “Sun City”

When he returned to the U.S., Little Steven wrote “Sun City” as a way to spread the word about apartheid. “The idea is not to offend people, but to raise some consciousness. It’s just to start the discussion about an issue that needs attention.”

He and two members of his band recorded the demo on a four-track recorder, as preparation to recording it with a larger group of musicians, and then he mobilized some extraordinary knowledge and talent to get it produced, promoted, and played.

“There was four of us equally important,” he explained. “Danny Schechter, who had been a real rabble-rouser from way back. Came from Boston and had been involved with that issue years before me [from the late 1960s as an anti-apartheid activist, representative of the exiled African National Congress with the South African Government, and CNN and ABC producer]. He was the reason why it was publicized at all.

“[Record producer and DJ] Arthur Baker offered his studio and his engineers and his musicians, and the record is his phone book.

“And Hart Perry filmed it. And if he hadn’t filmed it, no one would’ve ever heard of it, because American radio wouldn’t play it. It was too black for white radio and too white for black radio. Any one of these four guys not involved, it wouldn’t ever have happened.”

And then there was Little Steven himself, who brought a career’s worth of experience songwriting, producing, and playing from Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes, the Miami Horns, the E Street Band, Gary U.S. Bonds, and of course the Disciples of Soul and his earliest bands.

The Disciples of Soul was multi-racial, and he wanted the musicians involved in the “Sun City” endeavor to likewise cross racial and ethnic lines. As Latin musician Ruben Blades pointed out, Steven was “ahead of the curve,” as no Latin artists had been included in “We Are the World.”3

Steven was also ahead of the curve in taking an inclusive approach to genre, ignoring the fact that MTV, one of the key avenues for dissemination and promotion, was segregated in its exclusion of “black music” like R&B and rap.

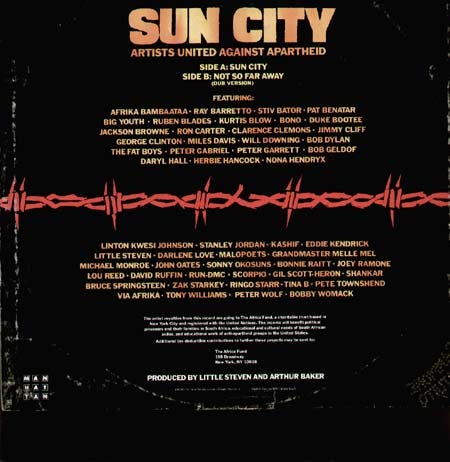

“There was nothing like it,” according to Peter Wolf of the J. Geils Band, one of the artists who participated. “Steven got together the different genres of music. Rockers, punk rockers, rappers, R&B stars,” as well as reggae, salsa, and jazz, a coming-together of an extraordinary collection of artists:4

Afrika Bambaataa, Stiv Bators, Pat Benatar, Big Youth, Rubén Blades, Kurtis Blow, Bono, Duke Bootee, Jackson Browne, Jimmy Cliff, George Clinton, Will Downing, Bob Dylan, the Fat Boys, Peter Gabriel, Peter Garrett, Bob Geldof, Daryl Hall, Nona Hendryx, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Kashif, Eddie Kendricks, Darlene Love, Malopoets, Grandmaster Melle Mel, Michael Monroe, John Oates, Bonnie Raitt, Joey Ramone, Lou Reed, David Ruffin, Run-DMC, Scorpio, Gil Scott-Heron, Bruce Springsteen, Via Afrika, Peter Wolf, Bobby Womack – vocals

Ringo Starr – drums

Zak Starkey – drums

Keith LeBlanc – drums, drum programming

Tony Williams – drums

Steve Jordan – drums

Little Steven – guitar, keyboards,[15] drum programming

Pete Townshend – guitar

Stanley Jordan – guitar

Keith Richards – guitar

Ron Wood – guitar

Doug Wimbish – bass

Ron Carter – acoustic bass

Herbie Hancock – keyboards

Richard Scher – keyboards

Robby Kilgore – keyboards

Zoë Yanakis – additional keyboards

Miles Davis – trumpet

Clarence Clemons – saxophone

L. Shankar – double violin

Ray Barretto – conga, vocals

Sonny Okosuns – talking drum, vocals

Jam Master Jay – scratching

DJ Cheese – scratching

Benjamin Newman – drum programming

B.J. Nelson – background vocals

Lotti Golden – background vocals

Tina B. – background vocals

Daryl Hannah – additional background vocals

Kevin McCormick – additional background vocals

The Dunnes Stores Strikers – additional background vocals

Annie Brody Dutka – additional background vocals

Robert Gordon – additional background vocals

Steve Walker – additional background vocals

Pete Townsend of The Who was convinced that they had the right approach. “I happen to think that we should impose sanctions, and I suppose the only sanction that a rock performer can impose, is to say ‘Listen, we’re not going to come and play until you do things right.’”

Gil Scott Heron believed that what they were doing was fundamental. “This country prides itself in being the land of the free. We should be able to understand most people who want to be free. And we should be in support of them.”

Steven asked the South African group The Malopoets to participate, but because some still lived in South Africa, warned them that “it could be dangerous to be on this record. Who knows what reprisals may happen. They told me, ‘We have to be on this record.’ When somebody tells you they’re ready to die to be on a record, that’s commitment.”

Of course Peter Gabriel, who had inspired Steven with “Biko,” was involved.

Hollywood film director Jonathan Demme (Melvin and Howard, later the Oscar-winning The Silence of the Lambs) directed the shoot to gather live-action footage inside the studio and on the streets of New York for a behind-the-scenes documentary.

That documentary, The Making of Sun City, won top honors from the International Documentary Assocation in 1986, while public television station WNYC aired it in 1987 and made it available to other public broadcasting stations across the country.

There has never been a song video before and since quite like the one for “Sun City,” nor many songs that can claim to be both powerful in their messaging and upbeat and inspiring in their tone:

Bono was so inspired by the other artists during the making of “Sun City” that he went back to his hotel room and wrote “Silver and Gold,” which was also recorded during the production, with Keith Richards and Ron Wood on guitar and Steve Jordan on drums.

Bono explained the lyrics during a U2 concert (included in the “Silver and Gold” track on the Rattle and Hum live album) as being “about a man in a shanty town outside of Johannesburg. A man who's sick of looking down the barrel of white South Africa. A man who is at the point where he is ready to take up arms against his oppressor. A man who has lost faith in the peacemakers of the west while they argue and while they fail to support a man like Bishop Tutu and his request for economic sanctions against South Africa.”

Likewise, Peter Gabriel and Indian violinist L. Shankar improvised a piece called “No More Apartheid.” As Steven recalled, “Peter Gabriel came in and just started chanting. Weird African chant, out of nowhere ... Then he started harmonizing with himself,” to which drum, guitar, and synthesizer were later added.

A line in Gil Scott-Heron’s song “Johannesburg” (1975) became the inspiration for “Let Me See Your I.D.”, in which Gil, Miles Davis, the Malopoets, Peter Wolf, and others participated.

Six versions of “Sun City” and two other songs — “Revolutionary Situation” and “The Struggle Continues” — were also recorded, resulting in the release of not only a single but an entire album, on October 25, 1985.

The take-down of Sun City

Steven was clear that, although the proceeds would go to the families of political prisoners in South African jails, he wasn’t doing the song as a fundraising vehicle and was not going to pull any punches with the content, unlike other benefit songs like “We Are the World.”

In fact, the song ridiculed Ronald Reagan’s policy of remaining friends and doing business with South Africa as a form of ‘influence’ on apartheid.

At his speech for the premiere of the video at the United Nations, Steven made his intention clear. “Although the money made from the sales of this record will go to help wherever it is needed, this is not a benefit record. Because though the black South African needs are great, they do not ask us for our charity. And though the black South African suffering is horrifying, they do not ask us for our pity. All they ask us is that we look at them and see them. Because by seeing them, we see ourselves. Their struggle is our struggle. Because their struggle is not against men — this is a temporary condition. Their struggle is against a disease, a disease called racism and bigotry.”

Steven also publicized the project by appearing on the popular Phil Donahue Show — opposite the Chairman of Sun City, Sol Kerzmer.

As was his wont, Phil (below) provoked debate with his incendiary introduction. “We’re in New York City talking about ‘Sun City,’ the most politically aggressive maneuver in the history of rock and roll.”

Sol Kerzmer laid into the “Sun City” video as “totally misrepresentative of the true facts. Why should Sun City then be linked with what you saw up there? Violence, and you saw up there barbwire. Those things don’t exist in Bophuthatswana, and they don’t exist at Sun City.”

Steven remained calm and reasoned. “Let’s get to the truth now. I want to talk about the truth. This is the truth. It’s not Sun City itself. It’s not the entertainment complex that’s the problem. It’s where it is. And where it is is where people are not free to go where they want to go. They’re there because they have been relocated forcibly. They have been put on a truck and taken hundreds of miles from their home, and dropped in this area. And they cannot leave. They cannot get visas or passports. Their citizenship has been stripped. And no one in the world recognizes this as an independent country except for the South African Government. So that barbed wire you see in the video is symbolic, and it is very true that these people are in a prison there. And all the people that Sol employs are not there by choice. That’s what freedom is all about. It’s about choice.”

Steven also stood his ground in interviews with the news media. When challenged by one interviewer around there being too many aid records, Steven respectfully disagreed. “No. I think as long as there’s injustice and problems in the world, we should talk about them, and rock and roll is the best communication we have.”

The steady and assured promotional efforts of Steven and his high-powered team were successful, with the almost-six-minutes-long single reaching #38 on the Billboard Hot 100 and getting airplay on all but a few radio stations in the south that had received threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

People got the message that South Africa was a place to avoid because musicians were taking a stand against it. Even musicians who had played there before (for extraordinary sums of money) agreed to honor the boycott, which had an economic impact on Sun City by impeding its ability to hire big-name musicians and attract tourists.

Through concerts and public statements, Steven and other musicians continued to apply pressure and the anti-apartheid movement gained further momentum.

Musician Johnny Clegg followed suit and created a local organization in South Africa similar to United Artists Against Apartheid.

Little Steven takes the Hill

Most artists would consider what Little Steven had pulled off as a job well done, and let’s get back to the day job of making music.

But not Steven, who meant it when he said “There ain’t no reform that’s going to fix this. These guys have got to go.”

As former New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley tells it, “There was a bill passed in the Congress, the Anti-Apartheid Act, and it was essentially economic sanctions against South Africa until they ended apartheid. And it was vetoed by [President] Ronald Reagan. Steve called me and he knew what the situation was. The Congress was now going to vote to override the veto or not. And he stepped forward and said, ‘I’m going to be part of that process.’ And he came down and made persuasive cases to a number of senators. Very impressive. We overrode the President’s veto.”

The bill became law on October 2, 1986.

Unfortunately, the sanctions were only partially enforced by the Reagan Administration, allowing the head of South Africa’s central bank to boast two years later that the country had been able to adjust to them.

“You want a battle, South Africa?” said the music community. “We’ll give you a battle.”

The Brits enter the war with Freedomfest

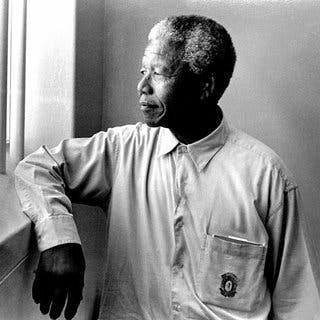

By 1988 the focus of the movement had become the release of Nelson Mandela, an anti-colonialist and nationalist leader who had already spent 26 years in prison while serving a life sentence for trying to overthrow the apartheid government.

Whereas the Government hoped that Mandela would die in prison of old age, the anti-apartheid forces decided to use his 70th birthday as an opportunity to stage an international call for his release.

On July 11, 1988, Freedomfest — also known as the Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute, Free Nelson Mandela Concert, and Mandela Day — was held in London’s Wembley Stadium.

It was an extraordinary eleven-hour concert viewed by more than 600 million people in 67 countries, organized by producer and impresario Tony Hollingsworth.

Unlike Live Aid, it was overtly political, including performances by all three of our featured artists — Peter Gabriel, Stevie Wonder, and Steven Van Zandt.

Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds, and Youssou N’Dour performed “Biko.”

Little Steven, Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds, Meat Loaf, Jackson Browne, Youssou N’Dour, and Daryl Hannah performed “Sun City.”

Stevie Wonder delivered heartfelt messages to the South African people by singing “I Just Called to Say I Love You” and “Dark ‘n Lovely,” and also spoke directly to Mandela, saying “Until you are free, no man, woman, or child, whatever color, is really free.”

The concert ended with fireworks over London while the opera singer Jessye Norman sang “Amazing Grace.”

When Steven returned to the U.S., he was upset when he saw a recording of the Fox broadcast of the concert that “de-radicalized” it by eliminating anything political, including speeches supporting the anti-apartheid movement and the performance of “Sun City.” Fox had ostensibly done so to keep its advertisers with ties to South Africa ‘sweet,’ particularly Coca-Cola.

Steven wasn’t about to take it lying down, complaining to the press that cutting five hours from the concert because the content was too political was “a totally Orwellian experience.”

Nevertheless, Peter Gabriel described Freedomfest as “a very emotional day, and it somehow accumulated this momentum, which was sort of snowballing. Although Mandela was clearly well known… he became an international icon in a different way after that event, I think.”

The fall of apartheid

In 1989, newly elected U.S. President George Bush instituted full enforcement of the Anti-Apartheid Act, including bans against doing business with South Africa.

The following year, amid the growing domestic and international pressure, President F. W. de Klerk released Nelson Mandela and worked with him to negotiate an end to apartheid and the repeal of the apartheid laws.

Steven described Mandela’s release as “the most thrilling moment of my life.”

When Mandela came to the U.S., he was feted at a celebration at a New York restaurant, where Steven introduced him and where actor Robert De Niro gave public acknowledgement that “Steven is really the person who started the whole thing here, and I thank him and we all thank him.”

In 1994, a general election was held in South Africa involving all races and Mandela led the African National Congress to victory with the slogan “a better life for all,” becoming the country’s first non-white president.

His coalition government brought about a new constitution and established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate the human rights abuses under apartheid, with the aim of ushering the country into a new racially integrated era unfettered by the trauma of the past.

And the drumbeat goes on

Of course the ending of apartheid cannot be seen as being brought about, or even led, by the music community, but it’s undeniable that it played a significant role in keeping the pressure on international institutions and governments to do their part to force South Africa to abandon its policy of apartheid.

In fact, after 1985, as a result of the unrelenting pressure from musicians and other activists, banks began to pull or call due loans to South Africa. As Steven noted, “That was the end. Once the banks cut them off, they had to let Mandela out of jail.”

Combined with cultural and sports boycotts and economic divestment activities from outside, and exacerbated by rising rebellion within the homelands and a U.S. ban on doing business with South Africa, the South African government became increasingly rejected and isolated within the international community. It was only a matter of time.

One thing we can say with confidence is that the support of the international music community through its persistent outpouring of protest songs like the three profiled in this post, and its holding of high-profile concerts and benefits like Freedomfest, not only kept the pressure on but also provided reassurance to black South Africans that they were not alone and encouraged them to sustain their hope and perseverance in the face of apartheid.

Beyond the effect on the people of South Africa, the protest songs were inspirational to other musicians, as we have seen. Steven Van Zandt’s exceptional efforts on behalf of South Africa were cited as especially inspiring.

Bruce Springsteen assesses “Sun City” as “an incredible creation. In my opinion, it was a very historic piece of music that I think really had an effect on apartheid and the way it was seen around the world.”

“That’s pretty impressive,” added Richie Sambora. “Politicians can’t even do that. Presidents can’t do that really. But he did. Put all those people together and made a change in the world.”

Steven’s ultimate intention was not just to bring about this one change, as important and as dramatic as it was, but to inspire others to follow suit. “A lot of people, especially once we did the Sun City thing, started to connect the whole rock music to politics. I’m starting to reach people in the way I was hoping to reach them.”

As Ruben Blades succinctly puts it, “He understands the need to utilize music not just as a means to escape reality, but to document it or confront it.”

One person who claims to have followed Steven’s approach and used it to significant effect is Bono, in his ongoing efforts to fight poverty and reduce debt in Africa.

Steven’s example has also been recognized and had an influence outside the music community.

“The fact that he is partially responsible for bringing down a government is extraordinary,” said Hollywood director Chris Columbus (Mrs. Doubtfire, Home Alone, The Help).

The documentary Steven Van Zandt: Disciple — I highly recommend the excellent trailer above! — actually came about as a direct result of Steven’s involvement in the anti-apartheid movement and the way in which he inspired filmmakers in the generations below him.

As the director and producers attest:

“I felt like people didn’t know that Silvio Dante [Steven’s character in The Sopranos] helped bring down apartheid and free Nelson Mandela and other people. They knew some of the story but not all of it, so that was incredibly exciting.” - Bill Teck, Director

“I had been a Stevie fan all my life. My earliest memories of Steven was being a little kid watching MTV and knowing that I wasn’t going to play Sun City. I first really became aware of him at a very young age.” - Robert Cotto, producer

“I think the whole Sun City time was something that was very influential to my generation. I had ‘End Apartheid’ bumper stickers in my bedroom because of Steven Van Zandt. So it's been a really exciting full circle moment when Bill invited me to be part of this, and it's been the thrill of a life.” - David Fisher, producer and cinematographer

Inspiration for the ages

Lest we think that the inspiration of protest songs fades away, David Fisher argues the opposite. “I think that Steven Van Zandt and his body of work is as relevant today as it was in the eighties, and especially his solo work. The nation now is very polarized. Steven was singing about this back in the eighties. I think he is an artist for today.”

Bill Teck argues that it isn’t just about the music, but about the integrity and passion of Steven as an artist:

“…The most interesting part is seeing that when it looks like things are going to go awry, you’re going to go, oh, maybe this guy's not who we think... No, he really is. He’s a mensch. He never takes the cape off. He and his wife Maureen are really passionate about saving rock and roll. [For] what a force for good it can be, and for personal freedom, no matter what that is. They feel like that’s a good thing for the world, and they’re still fighting to keep that alive. That became our North Star [in the documentary]. Once you saw that Steve was really all there in his work, there wasn’t a lot of personal dirt to dig up. It was really about his passion for music and rock and roll.”

Steven continues to be a force for change with his Rock and Roll Forever Foundation and its TeachRock national K-12 curriculum that teaches music in context as history and culture and not just as entertainment.

Perhaps we should end with this inspiring quote attributed by Ralph Waldo Trine to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe — which could have been written about Steven (as well as Stevie and Peter):

“Are you in earnest? Seize this very minute:

What you can do, or dream you can, begin it;

Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.

Only engage and then the mind grows heated;

Begin and then the work will be completed.”

Sources

The two primary sources are:

Steven Van Zandt: Disciple. HBO Documentary Films, 2024. (Bill Teck, Director)

Stand and Be Counted: Making Music, Making History - The Dramatic Story of the Artists and Events that Changed America, by David Crosby and David Bender (HaperCollins, 2000).

Other sources include:

“Stevie Van Zandt: ‘My religion switched right over to rock ’n’ roll’”, The Guardian, David Smith interview with Steven, June 26, 2024.

“Inside the Steve Van Zandt documentary that the rocker didn’t want to make,” Fortune, by Hugh McIntyre, July 22, 2024.

“Transcript: ‘Unrequited Infatuations’ with Stevie Van Zandt”, The Washington Post, Jonathan Capehart interview on Washington Post Live, September 28, 2021.

Wikipedia entries on Steve Biko, Nelson Mandela, Steven Van Zandt, Artists United Against Apartheid, Sun City (Album), Sun City (Song).

He was called Miami Steve after he returned from Miami and kept wearing Hawaiian shirts in the cold of New Jersey. I’m going to refer to him in this post as Steven or Little Steven to distinguish him from Stevie Wonder.

His "I Am a Patriot” became so associated with longtime activist Jackson Browne, who liked to perform it in concert and included it on his 1989 album World in Motion, that many thought it was Jackson’s song. Pearl Jam would ‘adopt’ it as well.

Note that all comments about “We Are the World” address ways in which the Sun City project decided to be different or had learned from that earlier project, and do not appear to be slurs on the song or its impact.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_City_(album)

Great piece Ellen! Steven Van Zandt is truly a force of nature. . . nice to be reminded of all the details surrounding the "Sun City" project. Gabriel's "Biko" and Little Steven's work certainly played a big role in informing me about South Africa at the time.

I'd forgotten the part about Reagan vetoing the anti-apartheid bill - that man is responsible for SO much bad shit that's been forgotten - and hooray for Bill Bradley coming through with support for Steven, love that story!

Love this! I still have this 7” somewhere. In a lot of ways, this was how I first learned about apartheid.