The strange and supernatural events behind "Eve of Destruction"

The protest song series

Welcome, everyone, to one of the final posts in the protest song series.

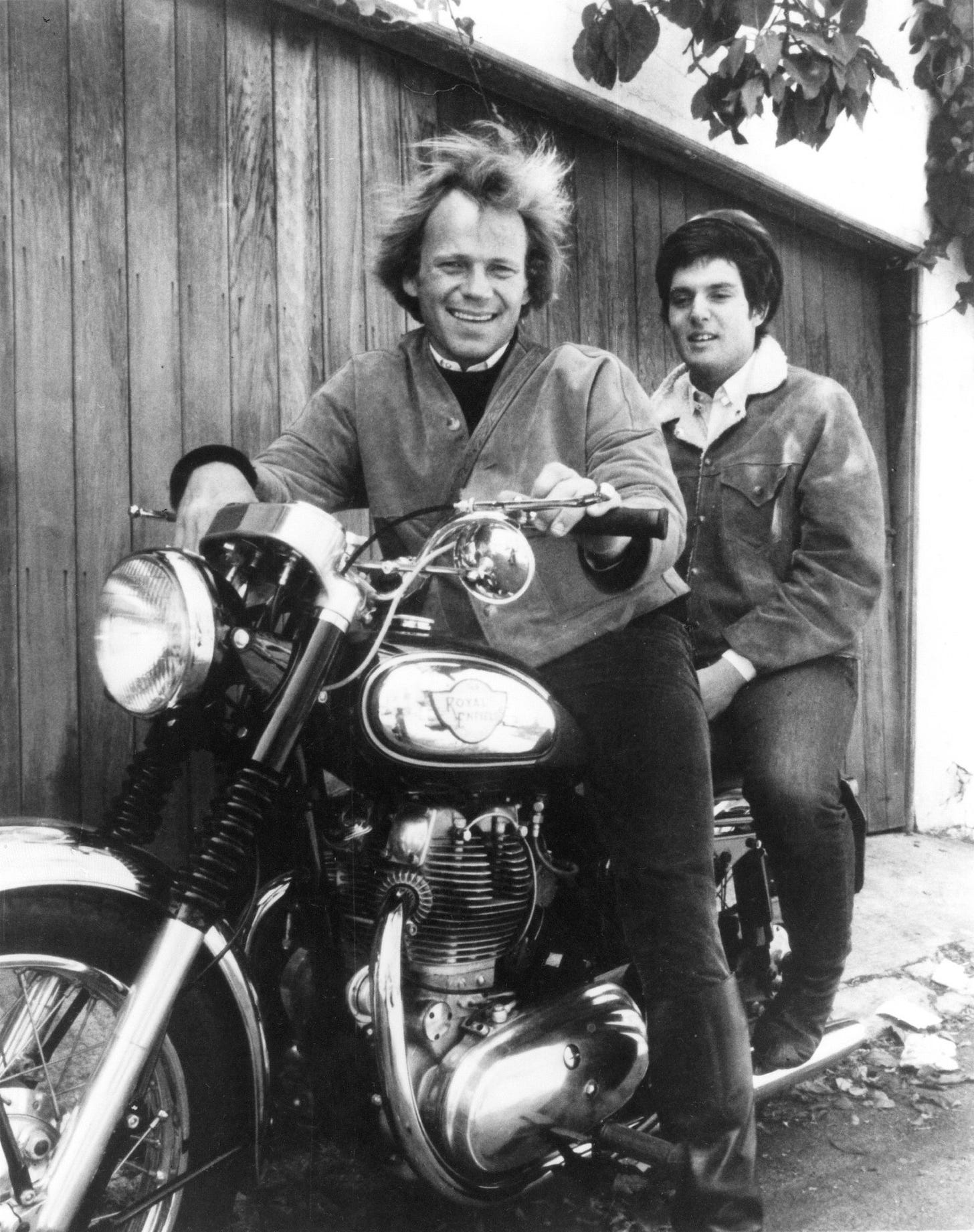

Today’s post should be subtitled ‘How one artist lost his rock ’n’ roll career and another lost everything because of a protest song.’ (Those artists are above.)

Some of the people in this story don’t come out smelling like roses, to say the least, and a couple of those are still alive. So the post is partially behind a paywall.

This is also the first in this year’s longer and more in-depth posts for paid subscribers, whose financial and emotional support I greatly appreciate.

Like so many tales emanating from the music industry, it’s hard to believe that the story I share with you today really happened. But I assure you, I compared sources and most of it seems to be true.

I could not verify the angelic visitation, however. As someone who writes fiction and knows how creativity can feel like it’s flowing through you and not from you, I actually have no problem believing that.

The head of a record label acting like a Mafia don and threatening death and destruction I can buy into as well. I’ve read too many stories of outrageous behavior by record execs not to believe it.

But there are other things…

So buckle up and get ready for a wild ride, because I’m taking you to the very edge of the “Eve of Destruction.”

An angel bestows five songs

One night, late in 1964, Phil “Flip” Sloan heard a voice that instructed him to place five pieces of paper spread out across the top of his bed. “Perhaps an angel’s,”1 this voice told him the first song was to be called “Eve of Destruction.”

Obeying the voice, Phil wrote the title at the top of one sheet and worked on the lyrics for several hours, with the voice making corrections as he went along. He argued and prayed for divine guidance. His generation “had a subsconscious feeling that we could be the last generation” if the problems captured in those lyrics could not be resolved.

Four songs followed. “The Sins of a Family” was about his teenage cousin Barbara, whose father had found solace in the bottle to deal with his post-traumatic stress disorder from World War II, forcing the family into financial difficulties and Barbara into performing sexual favors for men in exchange for money to pay for her schooling.

On a more positive note, “This Mornin’” was about the world being full of sorrow and worry until we find the light within and help change the world without.

Two songs were inspired by his musical heroes, “What’s Exactly the Matter with Me?” being an homage to Woody Guthrie and “Ain’t No Way I’m Gonna Change My Mind” a form of “comic relief” and wisdom inspired by Bob Dylan.

The next morning Phil added melodies to the words.

The birth of P.F. Sloan

Earlier, in 1957, Phil had driven his dad crazy playing a one-string ukelele he received as payment for a babysitting job, so his dad took him to Wallach’s Music City in West Hollywood and bought him a cheap Kay guitar in a triangular cardboard carrying box.

Phil became a frequent visitor to Wallach’s, where he could listen to records without buying them. Taking his guitar with him one day, he found police guarding the doors against hordes of girls, but, upon seeing his guitar case, the cops concluded that he was a musician and let him in. As Phil tells the story, it turned out that Elvis was in the store getting a guitar gold-plated, and he gave 12-year-old Phil a spontaneous hands-on music lesson while waiting for the gildwork to be completed.

The next year Phil put out a single called “All I Want Is Loving” / “Little Girl in the Cabin” on R&B record label Aladdin Records. Two years later he got a songwriting job with Screen Gems, the largest music publishing company on the West Coast.

The musically precocious 16-year-old formed a writing and performing (and later producing) partnership with a fellow songwriter three-and-a-half years his senior, Steve Barri. They dubbed themselves with a changing parade of names, including Philip and Stephan, The Rally-Packs, The Wildcats, The Street Cleaners, Themes Inc., and The Lifeguards.

In 1963, executive Lou Adler (below) decided to use them as backup singers and musicians — Phil on guitar and Steve on percussion — for Top 10 surf song hitmakers Jan and Dean. Phil was also commissioned to sing the lead falsetto ascribed to Dean on the duo’s hit “The Little Old Lady from Pasadena.”

This led to vocals on surf songs by the Rip Chords and Bruce & Terry, as well as recording their own surf album as The Fantastic Baggys, touted as “the most exciting surf group in the country.” Here they are doing “Tell ‘em I’m surfin’”:

In 1964, Adler hired them for two companies he co-founded — record label Dunhill Records and publisher Trousdale Music. Important to remember for later in this story is that Adler had several partners in these new enterprises: long-time record executive Jay Lasker (formerly of Decca, Vee-Jay, and Frank Sinatra’s Reprise Records), producer Pierre Cossette, and dancer and manager of musical acts Bobby Roberts.

Adler brought an impressive pedigree himself, having, with Herb Alpert, written (among other songs) Sam Cooke’s hit “Wonderful World” and managed Jan and Dean’s successful career.

Dunhill’s first album release would be a collection of surf instrumentals by the Rincon Surfside Band, none other than Phil and Steve, later reissued by RCA under the name “Willie and the Wheels.”

Phil and Steve soon justified their doubled salaries at Dunhill by writing, producing, and playing on a steady stream of songs for a variety of artists and groups.

Phil played lead guitar on these tracks and generated several famous riffs, one on “Secret Agent Man,” which became the theme song for British TV show Danger Man, and another being the intro to The Mamas & The Papas’ “California Dreamin.’” He also played with the famous group of L.A. session musicians called the Wrecking Crew.

Phil and Steve would also co-write several Top 20 hits — Herman’s Hermits’ “A Must to Avoid” (#8, 1965), Johnny Rivers’ “Secret Agent Man” (#3, 1966), and the Turtles’ “You Baby” (#20, 1966).

But the biggest hit would turn out to be one of the songs penned by Phil under supernatural guidance. None other then “Eve of Destruction.”

Phil no longer viewed himself as “Flip,” a guy whose aspiration in life was to be a happy, normal, and loved individual — and to be Elvis. On that night, he believed that he had been introduced to “a higher form of consciousness.”

Now, he “wanted truth and honesty.” Now he was P.F. Sloan.

When he played the new songs for people at work, Steve reportedly told him “I hate that kind of shit!,” while Adler rebuked him for wasting time on tunes that were unpublishable.

Phil thought his boss was out of step with the times. “Adler did not see any future for the folk expression. He was still banking on surf music and girl songs. But the tide of that scene was going into ebb.”

Once Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home went top 30, Adler gave Phil permission to make some demos.

It didn’t go unnoticed by Phil that as he played guitar and harmonica for the “Eve of Destruction” backup track, partner and producer Steve Barri and engineer Chuck Britz were in the control booth talking and laughing and showing a lack of regard and respect for this divinely inspired song.

A guy just looking for a ‘green’ song

Barry McGuire was a welder who fell into music and found it to his liking.

In 1963, as a member of New Christy Minstrels, he scored a Top 20, Grammy-nominated hit called “Green, Green” as co-writer (with Minstrels co-founder Randy Sparks) and lead singer.

“Green, Green” showcased an unusual voice that required the right sort of song to take full advantage of its timbre and rawness:

Folk-pop supergroup The Kingston Trio also had success with Barry’s song “Greenback Dollar.”

In the winter and spring of 1965, departing the New Christy Minstrels to seek less restrictive and ‘greener’ pastures, Barry spent many frustrating and fruitless months looking for a record label and publishing company with unrecorded songs. He wanted to go solo.

One evening in April his luck turned when he went to Hollywood nightclub Ciro’s where his friends Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark and the rest of the Byrds were celebrating the release of their hit single, “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Who happened to be there but Lou Adler, who recognized Barry bopping up and down on the dance floor and invited him to stop by Lou’s office to discuss the next step in his singing career.

Of course Barry took him up on his offer, but turned out he wasn’t really turned on by any of the available songs Lou played for him. So the label head sent Barry to meet “the kid down the hall” and see if any of Phil’s strange tunes might appeal to him.

Barry was flattered that “the kid” knew his hits, and to both his and Adler’s delight loved the song “What’s Exactly the Matter with Me?” and liked some of the others. He wasn’t that enamored with “Eve of Destruction,” but included it in his list of ‘possibles’ in case they needed a fourth song.

Just a greasy lyrics sheet and a throwaway demo

Adler signed him to the label and scheduled recording sessions in July with members of the Wrecking Crew — Hal Blaine on drums and Larry Knechtel on bass guitar — and of course Phil on guitar and harmonica.

Producer Lou Adler and engineers Bones Howe and Chuck Britz were in the booth, with co-producer Steve Barri coming in and out.

After recording “What’s Exactly the Matter with Me?,” eating some fried chicken, and doing “Ain’t No Way I’m Gonna Change My Mind,” they had only 20 minutes left. To fulfill Dunhill’s quota for the number of songs done in a session, they turned to “Eve of Destruction.”

Once they had laid down the backing track, Hal Blaine called the song “amazing” and Bones Howe told Adler “You’ve got a hit track here.”

With the clock about to run out, they could only manage a couple quick passes at the vocals. Barry recalls:

“I got my lyrics that I’d had in my pocket for about a week. I smoothed all the wrinkles out of them, and we wrote the chords down on a piece of brown paper that somebody got some chicken in or something, and we folded little creases and hung them on the music stands and went through it twice. They were playing and I’m reading the words off this wrinkly paper. I’m singing, ‘Well, my blood’s so mad feels like coagulatin’, that part that goes, ‘Ahhhhhh, you can’t twist the truth,’ and the reason I’m singing ‘Ahhhhhh’ is because I lost my place on the page. People said, ‘Man, you really sounded frustrated when you were singing.’ Well, I was. I couldn't see the words. I wanted to re-record the vocal track, and Lou said, ‘We're out of time. We'll come back next week and do the vocal track.’”2

Phil recalls everyone’s excitement being dampened by general agreement that this song could never be released as a single. “The track is great, guys,” Lou agreed. “All the tracks are great, but this song? I don’t think so.”

Barry looked visibly relieved.

From flame to inferno

There are at least three different versions of what happened next. Which you prefer may depend on whether you believe in divine intervention.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rock 'n' Roll with Me to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.