Welcome, everyone, to the first post in the Women in Rock series.

The overarching question of this series is: How have any women managed to succeed in the testosterone-driven, alpha male world of rock music?

In other words, what do they ‘got’ that other women — and, let’s face it, most men — don’t got?

To put it another way, what’s the XX factor that makes them different and special?

Or, are they an alien species living among us?

That final question is obviously a joke. (Not if you ask my brother.) But maybe there’s a kernel of truth in it, like there is in most conspiracy theories. Because there’s something ‘alien,’ something outside the norm, about these women.

One of my hypotheses is that they are successful precisely because they are comfortable residing in a largely male world and playing by those rules.

But to take that even further, I wonder if their success is down to having the perfect integration of ‘qualities’ from both genders — male and female — needed to make it in the rarefied world of commercial rock ’n’ roll.

This may sound sacrilegious to either gender, but I’ll say it anyway. Do they have a male brain in a female body? A male sensibility? A male something that makes them thrive in such a male-oriented and downright female-unfriendly world. (If you don’t believe it’s unfriendly, see the next section.)

Don’t worry, I’m not going to ask them to take tests to measure their testosterone levels (or prove that they’re not aliens). Among other things, I’ll be looking at what they were like as kids, who they like to hang out with, ways in which they’ve never fit in, how they get along with the guys, stuff like that.

That means that we’ll be learning a lot about the male artists they have interacted with, and about the industry as well, so this isn’t going to be focused only on the women.

We’ll be looking at these female artists within that larger context and how they managed to succeed when so many others — both male and female — failed to do so.

Let’s look at why this is such a fascinating context.

A quick note before we start, which applies for the entire series.

I’m likely to use a lot of words to refer to females, including girls, gals, chicks, birds, ladies, lasses, lassies, ‘old ladies,’ sisters, broads, babes, kittens, womenfolk, and whatever else works in the context of what I’m writing.

Likewise, I’m likely to use a lot of words to refer to males, including boys, guys, blokes, dudes, chaps, lads, boyos, brothers, bros, fellas, geezers, cats, menfolk, and, again, whatever works in context.

There’s also no doubt that, when I quote people, we’re going to encounter a range of expletives and profanities.

We’re talking here about the use of the vernacular, meaning everyday language and colloquial speech, and in particular the use of slang terms in different time periods, and as someone who leans towards the quirky and comedic, rather than finding such terms offensive, I tend to find them interesting and often humorous.

Like, how did women come to be called ‘chicks’ and ‘birds,’ or men ‘cats’ and ‘dudes’?

Or why did the Rat Pack (below) and a lot of men in my dad’s era refer to women as ‘broads’? (Turns out it was originally criminal slang and doesn’t have the most obvious meaning.)

Language has important meaning within context, and in my view we must consider it and apply it using that lens.

Also, it gets tiresome for me having to write and for you having to read the same nouns over and over again. Language variety is truly one of the important spices in life.

So please consider yourself informed and forewarned.

From the ‘Mamas’ to the ‘Papas’

I didn’t realize it, but things in the folk world were pretty much exactly the opposite for women than they would turn out to be in the rock world.

As Michael Walker writes in Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood (below), “The folk movement of the early ‘60s had been built on the success of sexually integrated bands like the New Christy Minstrels and Peter, Paul and Mary. Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Carolyn Hester, and Judy Henske had achieved success unmatched by solo male folksingers, spectacularly so in Collins’s and especially Baez’s case.”1

The folk movement did appear to welcome women in a way the rock world would not, but the phenomenal level of success of Joan Baez and Judy Collins, from what I’ve found in researching previous posts, was not a foregone conclusion, and a shedload of personal sacrifices had to be made that were not demanded of their male counterparts. Both Joan and Judy will be covered in this series.

And let’s also be honest, they were both extraordinarily talented but also remarkably beautiful women. We will have to look at the role of beauty in this series, because it’s a factor that cannot be denied. The women allowed into the boys’ clubhouse were almost exclusively pretty, sexy, or both.

Someone like Cass Elliot, despite her industry experience and stellar voice, had to stand outside knocking on the door, pleading for a chance, and ingratiating herself with Papa John, the leader of The Mamas & The Papas club, a good long while before he agreed to let her in, and even then reluctantly. Because of how she looked. Michelle and Denny (Cass’s bandmate in the Mugwumps) didn’t even have to knock.

But let’s get back to the really important point that Michael Walker is making here, which is that the folk movement stood in direct contrast to the music to come. Rock music raged in from across the pond, demanding breast-beating, headbanging allegiance from the men and doe-eyed submission from nubile young women, or, more accurately, girls in that sweet spot between attaining puberty and graduating from high school. (Picture in your mind those crowds of girls chasing after and crying over the Beatles.)

“And so the matriarchal culture of the 1950s was dispatched,” Walker observes.

“With the rise of the Beatles and fellow all-male British invaders like the Rolling Stones, Kinks, Yardbirds, and Animals and the American, especially Los Angelean, bands who aped their duende2, from haircuts to harmonies, women were held at bay by sheer masculine preemption.”3

Young males showed no hesitation in booting the women-worshipping folkies out the nightclub door and off the charts and welcoming these new musical apostates into their hearts, headphones, and homes, and set their hand to fashioning a newfangled youth movement that came to be called ‘the counterculture.’

And why wouldn’t they? The music was astounding and the new look pissed off the parents, as it should. And it attracted the girls, big time.

The girls in all the excitement wanted in.

But, according to Walker, “Where, exactly, women fit into the counterculture with its intimate ties to music performed by male musicians marketed by male record company executives, booking agents, managers, and concert promoters, and played by male disc jockeys, was not even a matter of debate. It wasn’t, in fact, debated at all. Beyond providing comforts creature and carnal, the young women of the 1960s closest to the burgeoning music scene in L.A. [and elsewhere] were largely excluded.”4

He shares the example of Judy Raphael, at the time attending the UCLA film school with Ray Manzarek (below right), who told her he was going to start up a band with fellow student Jim Morrison (below left). That band, of course, became The Doors.

“Can I be in it?” she asked.

“No, there aren’t any girls in rock bands,” he replied. “You need to stop running around trying to be somebody all the time.”

Don’t shoot the messenger here, Doors and Ray Manzarek fans! It was a different era, and we’re going to see guys (and girls) back then saying and doing stuff that they wouldn’t say or do now. Expect a lot more of this and consider it within that historical context.

What seemed almost overnight, things went from Judy Collins and Joan Baez performing in front of up to ten thousand people at a time, to boys like Ray Manzarek advising obviously bright and talented girls like Judy Raphael, who had been accepted into one of the most prestigious and hard-to-get-into film schools in the country (and one of only six girls there), that, as she puts it, “…you should just be a chick.”

“Ambition was a downer,” she concluded. “You got back into the traditional roles.”5

The egalitarian folk music that had played such a prominent role in the early sixties was being pushed off the stage and into the wings, and the eminently pragmatic and adaptable Bob Dylan went along to get along and caused an uproar by strapping on an electric guitar at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965.

The message to ‘chicks’ in all this? Go ahead and play your little acoustic guitar there, honey, but keep your little lady fingers off anything that plugs into an amp and has the power to knock people over and blast their eardrums to smithereens. That’s a dude thing.

Where did this leave all those girls with musical chops and aspirations to make it in the rock ’n’ roll world?

“There was a place for women in the ‘music biz’ all right,” Walker continues. “As torch chanteuses, teen angels, back-up singers, Mary Quant dollies, song stylists, autoharp/dulcimer-strumming folk madonnas [and] girl groups. Rock Inc.’s experience of women extended for the most part to waitresses, stewies, fans, flacks, groupies or, that most comic condition, rock wives.”6

We will be looking at some of these other categories in this series, because they are part of this world and reveal the underbelly of how it operates and what it takes to succeed.

Being a groupie, for example, is widely misunderstood as the province of ‘bad girls,’ when the reality is that these girls used all kinds of strategies to run the gauntlet required to gain access to rock bands and curry the attention of the band member(s) they wanted.

Witness the lengths to which Penny Lane (below) went to mesmerize and entertain the entire Stillwater band in the Cameron Crowe film Almost Famous in her bid to get close to both the music and her heartthrob Russell Hammond, played by Billy Crudup.

Sure, Kate Hudson is beautiful, but her character knew what she wanted and, working with her Band Aid compatriots (for example, Polexia Aphrodisia above right, played by Anna Paquin), found inventive ways to get it. From reading a few groupie autobiographies, my initial impression is that becoming a sought-after groupie was a highly competitive and even ruthless gig once a band made it big.

And some of these groupies even married their conquest, which also had distinct advantages, as well as the downsides to which Michael Walker seems to be alluding in calling it “that most comic condition.”

We’ll look at some rock wives and their stories, including Pattie Boyd who was married to George Harrison and then Eric Clapton, her sister Jenny Boyd, married to Mick Fleetwood, Jo Wood, long-time partner of Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, and that infamous rock wife, herself a musician, whom many blame for the breakup of the Beatles, Yoko Ono.

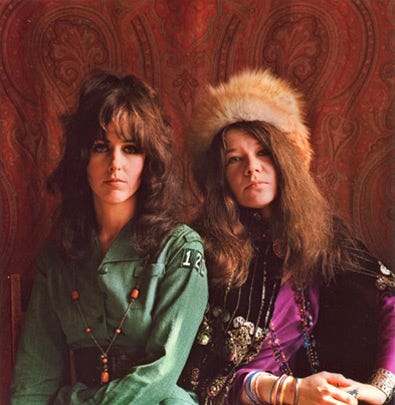

The boys in the clubhouse would not manage to keep out the girls who wanted to participate and not just spectate or support for long, however, “as the de facto prohibition on women performers in the rock idiom was tenuous and would soon be breached by Signe Anderson and Grace Slick (below left), the first and second singers of San Francisco’s Jefferson Airplane, and most spectacularly by [Janis] Joplin (below right).”7

I mean, do these two look like they would put up with any you-know-what?

Janis will be our first rock artist to be profiled, mainly because I devoured her road manager’s biography on her and became fascinated with the dramatic divergence between who she really was and where she dwells in the popular imagination.

Grace is also on my list. So let’s talk next about who and what this series is likely to cover. (You know me, I don’t make promises given how often I veer off course.)

Janis and beyond

If you haven’t read it already, you might want to read my post on how I came to the idea to write this series (although it’s not necessary to do so).

In that post, I explained that I will only be using first-person, biographical or autobiographical writings or interviews of people who were there. Ideally, writings and interviews of the artist herself.

In the case of Janis Joplin, for example, I am using two biographies, one by her road manager, John Byrne Cooke, and one by her publicist and close friend, Myra Friedman,8 who also did interviews with many of Janis’ nearest and dearest.

If sources of this kind are not available, I won’t be doing a post on that artist. Believe me, there are quite a few artists I’d love to cover but in my research I’ve found that there’s just not enough insider source material to do them justice.

The reason why I’m approaching it like this, and why I’m adamant about not resorting to secondhand sources, is because things can be very different from the inside looking out rather than the outside looking in. Famous artists tend to reside within a bubble consisting of an inner circle and people who are allowed access for specific time-limited purposes. Beyond those two concentric circles are everyone else, on the outside looking in.

Some artists can walk around unrecognized and unassaulted; many can’t. That’s quite a different world from what most of us experience.9 I’m not interested in people observing and opining on artists from a distance unless they’ve been in that world themselves, understand it intimately from first-hand experience, and know the artist personally.

Case in point about what it’s like to be in this bubble. The last remaining member of The Monkees, Mickey Dolenz (below),10 talked about his coming-of-age as a rock-and-roll star in a recent interview in The Guardian:

“The series was green-lit and the Monkees proved so successful at parting young people from their disposable income that, within a year, Dolenz was unable to visit the shopping mall near his parents’ home in San Jose without causing pandemonium. ‘I go through the big glass doors and all of a sudden there are people running, screaming. I thought it was a fire. I hold open the big door and I’m going, “Slow down! Don’t run! Don’t panic! It’s all right!” And suddenly I realised they were running at me. I was like, “Oh God!”’”

As he admitted, “‘I’ve always known that Micky the wacky drummer on television was who the girls were in love with — not me, Micky Dolenz, who grew up in the Valley. Now that’s easy to say, but sometimes very, very difficult to do. But if you don’t keep that separation, it can be disastrous. We see that happen all the time. An interesting, weird place to be.’”

It’s that “interesting, weird place” that I’m interested in. How the artist experiences it, what they do to navigate it, and in what ways it becomes disastrous if they don’t manage to keep that psychic separation between the rock ’n’ roll fantasy and the real person behind the rock star persona.

For the artists in this series in particular, young women breaking down barriers in a world peopled almost entirely by men, many of them spending long periods of time isolated from their families and friends and from other women who could give them advice, support, and a shoulder to cry on, residing in an idiosyncratic and often surrealistic reality inverted from the way most of the rest of the world lives, and, unlike men, expected to stay thin and attractive despite the profuse opportunities to indulge in substances — including catered and copious food — as part of the ‘sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll’ lifestyle, how do they do it?

What distinguishes them from their male counterparts? What sets them apart from women who didn’t make it? How do they account for their own success?

These are the things that intrigue me.

To that end, I will be bringing both my psychology and research backgrounds to bear, and have already been developing some very different views on things that are taken as gospel in the popular culture.

Some of the shibboleths of rock ’n’ roll may not survive. And they probably shouldn’t.

It’s also important to stress that I’m not in the business of passing judgement or smearing reputations, but artists and those around them are people and, like everyone, they don’t always act in honorable or chivalrous ways, especially behind closed doors.

So I can’t guarantee that everyone will be coming up smelling like roses all of the time. But I can guarantee that I’m not interested in hearsay or gossip or slander. If a seemingly reliable source claims that someone else did or said something, and I judge it important to include, I will identify the source of the allegation and let them own what they’ve claimed.

My interest is in understanding and explaining behavior rather than condemning it. With the high childhood trauma rate among musicians, as related in one of my recent posts, acting out and using a variety of mechanisms to survive, cope, and succeed are to be expected, especially in this rarefied context and given the shenanigans of the perfidious music industry. By the end of this series, we should have an interesting laundry list of such mechanisms.

Who’s that girl?

At the moment I have a spreadsheet with 41 women rockers for whom there is enough first-person source material to cover them in this series.

In a few cases, one or more artists will be covered together because that’s the nature of the source material. For example, Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart put out a joint autobiography.

I am indebted to Charles at Zapato’s Jam, who writes a lot about women rockers, for reviewing the list, contributing names, and helping me get clarity on my focus, as well as providing very useful listings of his relevant posts.

Although he covers women rockers around the world, I will be limiting myself to only those in the U.S. and UK. The reason for this is that these are the only two contexts for which I have some depth of understanding, having spent long periods living and working in both. I feel comfortable understanding and interpreting behavior within these contexts in a way I wouldn’t if the artist were from, say, Sweden or Indonesia.

Because of this geographic limitation, the period being covered is the inception of rock-and-roll in the 1950s/60s, e.g., Tina Turner, until today. However, because of changes in the rock landscape in the US and UK, the last artists on my list, e.g., Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney and Neko Case of The New Pornographers (who also has a substack called Entering the Lung), started their careers in the 90s.

One of the reasons for this absence of women rockers who debuted in the new millenium is the lack of adequate source material. They’re just not yet at a stage in their career where they’re writing autobiographies or insiders are writing about them or their band.

I also suspect that the evolution of the music landscape, in which rock has become a secondary genre when compared to pop and hip-hop/rap, has led to the Taylor Swifts and Harry Styles being the younger artists getting the publishing offers to write their life stories, along with (as we’ve seen) the aging megastars like Elton John and anyone who has had anything whatsoever to do with The Beatles.

If we get to the modern era (post-1996 or so) and the autobiographies of newer musicians dry up, I will consider resorting to source material largely composed of interviews. We do have women still kicking arse in rock ’n’ roll, even if they’re not household names in the same way they might have been in the golden era of classic rock. The lessons to be learned from how they have attained success and longevity may be even more pertinent and important in terms of how to make it as a rock musician today. So I don’t want to ignore or shortchange them as part of our story about women in rock.

In terms of adding names to the master list, some of you already gave me names of women you wanted me to cover back in early January when I first introduced this topic, which I duly added. (Thank you for your suggestions!) But quite a few of you are new to this substack.

If there are women rockers you would love me to cover, please let me know in the comments. I’ll check them out and add them if they’re not already on the list. (It also lets me know which women rockers you’re keen to read about.)

My current plan is to proceed in somewhat chronological order, but if you’ve been with me for a while, you know that I’m not a rule-follower. If something grabs my interest, I divert from the plan and pursue it.

Which is why I’m starting with Janis Joplin even though she’s not the first on my chronological list. That would be Tina Turner, although Charles has suggested including the Godmother of rock ’n’ roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

I’m not entirely sold on including Sister Rosetta just because she seems to be more of a progenitor and influencer of 50s and 60s rock ’n’ roll, like Muddy Waters, and a better fit in the gospel, blues, and jazz categories.

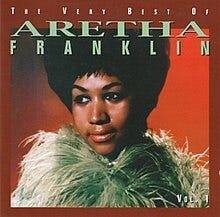

But then I’m struggling with whether to include Aretha as well, who’s clearly more pop, soul, and R&B. Having grown up with Aretha and knowing her music, I’m more inclined, even keen, to cover her. (Plus the fact that I saw her perform during an early 80s lull in her career and she was still blowing the proverbial roof off the joint.)

If you have a view on whether I should cover these two icons, Rosetta and Aretha, please do let me know in the comments. As I said, I’m not a slave to any rules, even the ones I put in place myself.

I should also mention that I have identified a number of other women in rock, e.g., groupies and wives, I aim to cover.

But I’m not coming up trumps with women in production, management, or technical roles for whom there is good source material. If you have recommendations, please let me know. I’m especially keen to cover these women given what I imagine would be their unique experiences with, and insights into, the music industry.

OK, that’s the gist of what I’ve been planning. I’m hoping that it will contribute to a significantly improved understanding of factors in musician success, for both men and women, and also where the music industry went right and wrong.

But most of all I’m excited because I think it will be fascinating. I look forward to taking this journey with those of you who are interested.

Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood, by Michael Walker (Faber and Faber, New York, 2006), p. 45.

“Duende or tener duende (“having duende”) can be loosely translated as having soul, a heightened state of emotion, expression, and heart. The artistic and especially musical term was derived from the duende, a fairy or goblin-like creature in Spanish and Latin American mythology. El duende is the spirit of evocation.” From Language Magazine.

Walker, p. 45.

Walker, pp. 44-45.

Example and quotes from Walker, p. 45.

Walker, p. 46.

Walker, p. 46.

A rare vintage edition I snagged in a used bookstore recently.

I once visited a famous religious site in Indonesia, this was in the 90s, and an Indonesian family apparently mistook me for someone famous. They snapped loads of pictures of me (without permission) and would run ahead of me so they could get shots of me walking towards them. I’m not built for that kind of attention. Keeping my hair combed, for one thing. Not looking cranky, for another. I hope they enjoyed their snaps, and I still wonder who they thought I was.

![Rare Myra Friedman BURIED ALIVE The Biography of JANIS JOPLIN 1973 William Morrow, NY [Hardcover] Myra Friedman Rare Myra Friedman BURIED ALIVE The Biography of JANIS JOPLIN 1973 William Morrow, NY [Hardcover] Myra Friedman](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Ch9K!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1d76da94-4a0e-421a-8e8a-a455f7778d94_319x425.jpeg)

Seems like the perfect time to mention the funkiest, most badass woman of all, Ms. Betty Davis! Her brazen confidence and rebellious spirit scared the shit out of every man and woman. For me, she is the definition of "rock & roll." Thankfully, her music is finally receiving its fair dues.

https://substack.com/@michaelfell/p-141591290

If I could come back as someone else, I’d want it to be as Tina or Etta James, minus the abusive relationships. Soul in abundance. Humanity too. And serious vocal chops.