Todd Rundgren as a producer - The Creator Series #4

How he does what he does as a producer and technology innovator

For the past two weeks we’ve been reviewing Todd Rundgren’s songwriting, performing, and producing career, and now we’re going to bring it all together. Today’s post is about Todd’s approach to his producing career, including his involvement with cutting-edge technology.

The final post will be on his approach to songwriting and performing in his post-Nazz career.

You can find the first Creator post on his career up to and including The Nazz here.

Below you will find links to the other posts related to his producing career (including his work with Fanny in the photo above), and if you scroll to the very bottom, you’ll find his producing discography.

Unless otherwise indicated, quotes below are from his autobiography, The Individualist.

How he became a producer

When Todd was with The Nazz, he apparently demonstrated an adeptness with recording technology that impressed Michael Friedman, the assistant to The Nazz’s manager and publicist, John Kurland. After quitting the band, Todd abandoned an idea he’d been entertaining of becoming a computer programmer and instead set his sights on becoming a producer, moving into New York and scouting out opportunities in Greenwich Village.

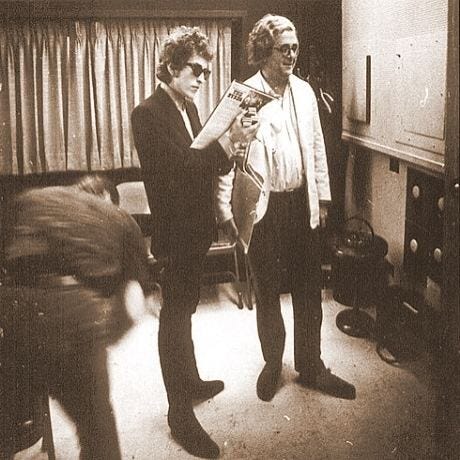

In the meantime, Michael Friedman had moved into a new post with Albert Grossman (photo below, with Bob Dylan). Grossman was the manager of many folk and folk-rock artists and bands, including Dylan, the Band, Janis Joplin, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Gordon Lightfoot, as well as the founder of Ampex Records and Bearsville Studios in Woodstock, New York.

Michael approached Todd about doing some engineering and production work for Bearsville:

“Somehow Michael Friedman, having been impressed with my fearlessness of recording technology, tracked me down in the West Village and invited me to meet Albert Grossman. There seemed to be a hole to fill in their approach to making records and I was soon tested on a number of stable acts and newcomers.”

The albums Todd was asked to engineer included Ian and Sylvia’s Great Speckled Bird and Jesse Winchester’s self-titled debut album. The latter was being produced by Robbie Robertson and accompanied by The Band, who asked him to engineer their next album.

In short order, Todd was promoted from staff engineer to house engineer at Bearsville, working directly for Grossman and with Grossman promising to make him the highest paid producer in the world. After engineering the Band’s Stage Fright album (see my post here), Todd became known as Bearsville’s “boy wonder.”

One of the things that Todd especially enjoyed about working for Grossman was the hands-off approach that gave him autonomy and freedom, Albert being consumed with his vast stable of high-profile clients. “The music industry is full of legends about super-managers who might have only one important artist — Colonel Parker and Elvis, Brian Epstein and the Beatles, Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin.” Albert had Bob Dylan on his roster, but tended to collect a lot of clients, some getting more attention than others, the upside from Todd’s perspective being “a certain freedom from scrutiny, which you might not get with a personal Svengali.”

His approach to producing

In an interview last year with Noise11.com, Todd explained that he tends to accept producing projects with a specific type of client, which have gotten him a reputation as “The Fixer”:

“I take someone who’s having problems getting the music out of their head and onto the medium, and help them get through that process. I evaluate the greater volume of what they’ve got. ‘I want to hear all your songs. I don’t want to make a record until I’ve heard everything you’ve got that you could possibly put in that record.’ Pick out the best of it. Refine it. Tweak it. There’s as much craftsmanship going into it as artistry in a way. There’s no formula to it. Each song is its own challenge in that sense… We don’t fit this into a box, we build a new box for this. That sort of thing.”

From experience he found that the producing process is as much about what comes before as it is about what happens in the studio:

“There are times in the studio when you think ‘this is too easy,’ that maybe good records are supposed to take a lot of time and effort. [Grand Funk Railroad] was probably around [the time] when I realized how important the work you do outside the studio is. That more than anything people like a good song and if you go into the process confident that you have a lot of good songs everything seems so much easier. More’s the better if you can play with some expertise or personal style.”

It’s also about a spate of decisions up until the product is delivered, with some artists unable to stop tinkering:

“When one sees a film or listens to a record or reads a book one is unaware of the options available to the creators and what informs the choices they make. You assume when experiencing something for the first time that it was always meant to be that way — what other way could it be? In reality, decisions are being made all the way up to delivery of the product about the best order to put things in and what should be expanded or removed, and even then some authors aren’t satisfied and continue to revise.”

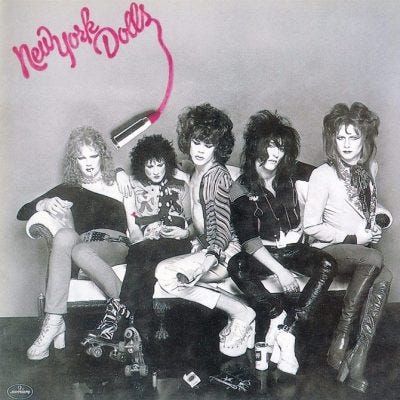

With his reputation for having a professional work ethic and adhering to budget and schedule, he was “anal” about delivering on time even if the artist wasn’t one hundred percent satisfied and still wanted to revise and tinker. As one label executive who attended the recording process for the New York Dolls noted, Todd didn’t “put up with bullshit” and took complete charge of the process, even to the point of yelling at the band to “‘get the glitter out of your asses and play.’”

As Todd wrote in his autobiography, “I don’t take it well if someone commits something to me and then doesn’t deliver, especially if they give you no warning, no opportunity to find an alternative… I’m often on some deadline and if they don’t deliver, I can’t deliver. I’m very anal about delivering.”

His relationship with the artist and label

Despite his commitment to on-time delivery to the label, he sees the artist as the real client because of the financial relationship involved:

“A record producer technically works for the artist, since the fee will be charged against their royalties. Most labels and artists don’t even grasp this simple relationship and often the producer is in the middle carrying water for both sides. In the end you do what’s right for the artist even if everybody wanted to fire you for it.”

“Artists and often producers themselves often don’t always understand the role one plays in the process. The producer does not work for the label or himself, he works for the artist. The artist ultimately pays the producer even if the label advanced the money. Artists misunderstand this when they feel like the producer is trying to make the record the label wants, and it must be explained to all that people don’t buy a record because it’s on a certain label. Producers misunderstand this when they think their reputation has anything to do with the success of the record because likewise, music is not bought because of who the producer was. The Artist will enjoy the glory or bear the scar of the final product.”

As an artist himself, Todd understood the financial realities and in some cases the financial plight facing many artists. In collaboration with Apple digital music executive Kelli Richards and his longtime manager Eric Gardner, he developed the concept for PatroNet, an internet platform that would allow himself and other creators to raise funds directly from the audience rather than having to market through labels or take loans. He designed the protocol and built the browser, and even signed up a couple thousand subscribers who paid a subscription fee in exchange for direct access to his works-in-progress and unreleased tracks. But ultimately he found that the time required to accommodate the technology changes and to address customer service issues was overwhelming, and put the project in limbo after “a decade of fits and starts.” He continues to offer new music to subscribers on his website and through independent labels, but has severed his relationships with the major record labels.

His approach with specific clients

I have covered seven of his producing projects in other posts:

his first major gig as a producer, doing The Band’s Stage Fright album (here) — that’s him in the Woodstock studio in the photo above

the record that appeared to cement his reputation as a hit-maker, We’re an American Band by Grand Funk (Railroad) (here)

his involvement in producing Badfinger’s hit singles off their Straight Up album, “Baby Blue” (here), and “Day After Day” (here)

producing the album Mothers Pride for the first all-female rock group to release an album on a major label, Fanny (here)

rescuing Meat Loaf and Jim Steinman’s Bat Out of Hell from never making music history (here)

doing the Patti Smith Group’s last album, Wave (here)

rescuing XTC from being dropped by their label with the album Skylarking (here).

One of the bands that Todd has produced twice, almost forty years apart, is the punk rock pioneers New York Dolls. He was asked to produce their self-titled debut album in 1973 when most producers were not interested because of the band’s vulgarity and outrageous antics, but he had a good relationship with them from socializing at Max’s Kansas City and accepted the project. He managed to get them through the recording process despite their lax work ethic, but with limited time and budget the band and the label rushed the mixes and cut corners on mastering. The album turned out to be a commercial failure but received universal critical acclaim and has been highly influential, causing Todd to quip that he had something to do with the anti-music movement. He also did the band’s fourth album, Cause I Sez So (2009), which also had positive reviews and reached #159 on the Billboard 200.

Another artist he has produced twice is Japanese singer-songwriter Hiroshi Takano. As Todd explains it, when the Japanese yen became very strong in the late 1980s, American performers and record producers became affordable and attractive to the Japanese. Todd received a double boon because it enabled him to take his 11-piece Nearly Human revue to Japan on more than one Japanese tour, and, on the back of those, Japanese artists asked him to produce their records in Japan or the U.S. He found himself, to his delight, producing Hiroshi and others with the most advanced equipment in Tokyo. Todd produced two of Hiroshi’s ten studio albums, Cue (1990) and Awakening (1991), the only ones to go to the top of the Japanese albums chart, reaching #2 and #8 respectively.

Staying on top of technology advances

As has probably become apparent, from childhood onwards Todd was intrigued by how things worked and quick to take things apart and figure them out. This extended to an interest in both analog technology and rapidly emerging digital technologies, resulting in his early adoption of product and process innovations and development of applications for use in recording, performing, and other spheres of musical endeavor. Not surprisingly, this brought him to the attention of some of the biggest players in the music and technology industries and resulted in his involvement in some cutting-edge technology applications, as we’ll see below.

Studio technology

His first major foray into, and personal investment in, technology was setting up his own recording studio in 1973. Despite having access to Bearsville Studios, Todd decided that he wanted a studio of his own and used loft space his friend and musical collaborator Moogy Klingman had rented at 24th and 7th in New York. He would call it Secret Sound. As he knew, having one’s own studio offered many benefits, including exercising ultimate control over studio design and operation, securing studio time when desired and at much lower cost, and being able to rent out the studio at commercial rates.

The tech geeks among you will understand the thrill Todd experienced constructing his ideal studio, based on first-hand knowledge as a performer, engineer, and producer of the design of most of the studios in London and New York:

“‘Quad’ was the new trend so I decided it should be set up for surround… I built the console in a workshop at Gotham Audio, pulling preamps and pots off the shelves to add to the Penny & Giles faders I had ordered from England. All was installed in a desk I had made out of wood and covered in blue snakeskin Naugahyde. I was fixated with graphic equalizers, so the board had nothing but busses in it, no eq, and everything else was outboard with a graphic on every channel. The tape machine was a Stephens 16 track like I was used to using at ID Sound. I collected a few bizarre odds and ends like a Cooper Time Cube and a Pultec filter and set about to connecting it all together… though it was a constant trial to keep it all working we were making real records. Secret Sound was a très beaucoup atelier.”

This was no ordinary studio. “I certainly did have my own odd opinions about how things should work — I had never been in a control room where every channel had a 20-band graphic equalizer on it. I had always intended to make odd records and ignore the rules that most studios had to live by to stay in business. It would have been a waste of space and effort if the music that came out was simply conventional.”

He proceeded to make A Wizard, A True Star (1973) in this studio as soon as it was usable, and his albums Todd (1974), Todd Rundgren’s Utopia (1974), and Initiation (1975) followed soon after. Albums by other artists recorded there included: three Harry Chapin albums (Legends of the Lost and Found, Living Room Suite, and Dance Band on the Titanic); Hearts of Stone by Southside Johnny & the Asbury Dukes; War Babies by Hall & Oates; Hallowed Ground by Violent Femmes; and two albums by Nils Lofgren, I Came to Dance and Silver Lining. (The studio closed in 1996, when Todd moved to Hawaii.)

Video technology

Fast forward about seven years and, “fascinated with the effects that had gone into Star Wars and [seeking] to use similar technology but with electronic media,” Todd invested his payoff from the Bat Out of Hell album (see my post here) in building “a serious collection of broadcast quality devices” to create content for the new laser disc format, in a deal with RCA. The commercial enterprise he established for this purpose created a demo video for RCA’s videodisc players, using The Planets orchestral suite by Gustav Holst as the soundtrack, which he premiered at a laser disc convention, and his video for “Time Heals” from his Healing album (1981) became one of the first videos to be shown on MTV. Unfortunately the technology didn’t take off, RCA abandoned the project, and the enterprise went kaput. As he laments, “While we strove for years to make a business out of it, and while we created a lot of fun video… the truth is I never seriously evaluated the commercial possibilities until after I bought all the stuff anyway. I just wanted to make video.”

Computer technology

In 1981 he got involved in computer graphics. “Ever since I saw that first digital paint box at [New York Institute of Technology] I wanted to get into CGI and studied all the literature and attended all the conferences and conventions to make sure I knew what the latest developments were. In those days a lone hobbyist could get his head around the concepts enough to produce what looked like an industry standard piece of work.” He developed one of the first computer paint programs, the Utopia Graphics System, which ran on an Apple II with a digitizer tablet.

Todd also co-developed graphic tablet software with a music theme for Apple in a technology venture in the late eighties. With Dave Levine, he designed and developed a screensaver product called Flowfazer (see example of one of the screensavers below), with the strapline “Music for the Eye.” They introduced it at MacWorld thinking they would publish it themselves, but found there was already well-funded competition with Berkeley Systems Flying Toasters and were forced to abandon the project.

Music streaming technology

In the mid-nineties Todd was approached by Time Warner Cable to develop a music application based on his interactive CD No World Order (1993) for an interactive television experiment the company was running in suburban Orlando (Florida). This would be an on-demand music service. He met with the special product divisions of the major record labels to get them involved in providing the music and every single one refused, even his own label. Two years later the project shut down, and two years after that Napster arrived and the uncooperative labels were overtaken by the inevitable arrival of music streaming.

As his autobiography ends when Todd is fifty, i.e., 26 years ago, we must surmise that he has pursued additional experiments applying and adapting technology that are not covered here. What we do know from interviews is that his producing career has largely tailed off in the new millenium, not through choice but through circumstance, as he explains below.

Why he isn’t producing anymore

In a video interview last year with Australia-based Noise11.com, Todd explained that he no longer does many producing projects with other artists because the industry has changed from an album to a singles orientation:

“I do it for myself, but I don’t do so much anymore [for others] because the whole thing has changed in a way. It used to be the album was the most important thing. The long arc of the record industry was, first it was singles. And if you got enough singles out, then you had an album because you had recorded a bunch of singles. Then the Beatles were the first so-called album artists. Sgt. Pepper was the first album that had no singles on it. There was no single on Sgt. Pepper. They had “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields,” but those were singles that didn’t appear on the album. So suddenly there’s this thing called an album artist, and that’s what I became. You get focus on the larger thing, not so much the smaller thing.

“The unfortunate thing now is we’re coming out the other end. And now because we have social media and the internet and the ability to release a song the day after you thought of it, now people just make a song… and they say we’ll put the song out. So we’re almost back to the age of singles again. Nobody or few people think in terms of the larger musical project. You do smaller things and then you accumulate them… I mean, if you look at the credits for a hit song, you might see six songwriters and four producers for one song. That’s not the kind of thing I do… And it doesn’t seem like music is [album rock] so much anymore. It’s just turn on the TR-8S [rhythm/drums machine] and start talking.”

He is, however, optimistic that things will change and become more amenable to album-oriented and other forms of serious music-making going forward:

“Everything is kind of fragmented again… Things have changed a lot. It’s not necessarily in a great place for musicians. But stuff changes all the time. Things always change. The feckless nature of music now won’t really last that much longer, I don’t think… It’s just the flavor of the week.”

Todd’s production discography

Hopefully, as Todd predicts, the album format will see a resurgence. In the meantime, there is a lifetime of album music already available to explore and treasure, including many albums performed or produced by him.

You can find his overall discography on either Discogs or Wikipedia, but only Wikipedia breaks it down into categories. Here’s Wikipedia’s current listing of the albums he’s produced:

Great Speckled Bird (1969) - Great Speckled Bird (Ian and Sylvia Tyson)

Jesse Winchester (1970) – Jess Winchester

The American Dream (1970) - The American Dream

Stage Fright (1970) – The Band

Jericho (1971) – Jericho

Taking Care of Business (1971) – James Cotton Blues Band

Straight Up (1971) – Badfinger

Halfnelson (1971) - Sparks

New York Dolls (1973) – New York Dolls

Mothers Pride (1973) – Fanny

Shinin' On (1974) - Grand Funk Railroad

War Babies (1974) – Hall & Oates

Felix Cavaliere (1974) – Felix Cavaliere

Bricks (1975) – Hello People

L (1976) – Steve Hillage

Bat Out of Hell (1977) – Meat Loaf

Remote Control (1979) - The Tubes

TRB Two (1979) - Tom Robinson Band

Guitars and Women (1979) - Rick Derringer

Wave (1979) - Patti Smith Group

Wasp (1980) - Shaun Cassidy

Walking Wild (1981) - New England

Bad for Good (1981) - Jim Steinman

Forever Now (1982) – The Psychedelic Furs

Party of Two (1983) - Rubinoos

Next Position Please (1983) - Cheap Trick

Watch Dog (1983) - Jules Shear

Zerra 1 (1984) - Zerra 1

What Is This? (1985) - What Is This?

Skylarking (1986) – XTC

Dreams of Ordinary Men (1986) - Dragon

Yoyo (1987) – Bourgeois Tagg

Love Junk (1988) – The Pursuit of Happiness

Karakuri House (1989) - Lä-Ppisch

Things Here Are Different (1990) – Jill Sobule

Cue (1990) - Hiroshi Takano

One Sided Story (1990) - The Pursuit of Happiness

Awakening (1992) - Hiroshi Takano

Halfway Down the Sky (1999) – Splender

The New America (2000) - Bad Religion

Separation Anxieties (2000) - 12 Rods

Cause I Sez So (2009) – New York Dolls

What an excellent deep dive - I like how you explained his philosophy that the mark of a talented producer isn’t just their sonic sense, but their understanding of how artists work best in the context of all their options.

Thanks for this summary and so much great research!