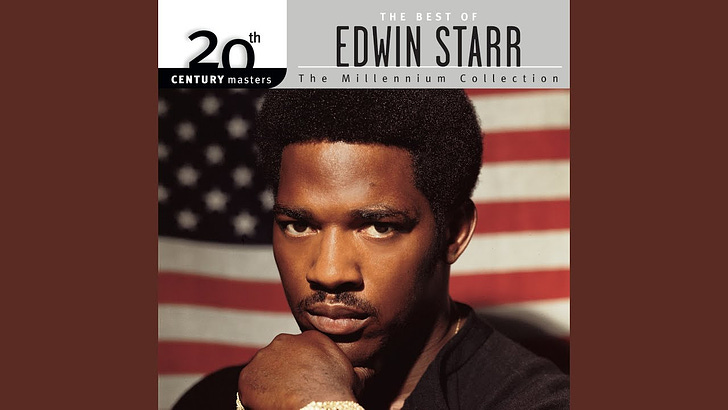

"War" by Edwin Starr (1970)

My favorite protest songs from the 60s and early 70s

Welcome, everyone, to the eleventh post in this series about my favorite protest songs from the sixties and early seventies.

So far we’ve heard quite a variety in terms of artist, style, and message:

“Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan (1963)

“Masters of War” by Judy Collins (1963)

“Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire (1965)

“For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound)” by Buffalo Springfield (1966)

“Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones (1969)

“Sweet Cherry Wine” by Tommy James & the Shondells (1969)

“Give Peace a Chance” by the Plastic Ono Band (1969)

“Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell (1970)

“Ball of Confusion (That's What the World Is Today)” by the Temptations (1970)

“Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (1970).

I’m pleased to share with you a playlist of 100+ protest songs put together by Mick McJesus of Mick’s Substack, which I’ll cover in more depth in an upcoming post on honorable mentions.

If you’re new, please check out Jackie R’s post sharing a song that makes fun of protest songs, as well as NickS’s post asking “What makes a good protest song?” in which he gives his own list of favorites — and where the Comments section has a discussion about this topic, which I’m sure Nick would be happy to have you join.

There will be two more of my favorite protest songs after this, followed by a list of honorable mentions that are also deserving of our attention. I’ll end with a summary post looking across the series and seeing what, if anything, this motley collection of protest songs tells us.

Today we have a Motown song about war that flew to #1 after producer Norman Whitfield fought to have it released as a single and convinced hit-maker and military veteran Edwin Starr to sing it — and which has become iconic.

Protest song of the day

In 1966, singer-songwriter Edwin Starr was happily performing at the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York City, when he learned through the grapevine that he’d been ‘bought’ by Motown.

You didn’t know musicians under contract could be bought and sold, did you? (Neither did I, until I started doing this substack.)

As Edwin later told UK interviewer Mark Stewart1:

“What happened is that I was in England on one of the many occasions that I was here doing a tour. And I went back to the United States to co-star at the Apollo Theater (below) with the Temptations, and one of the Temptations informed me that I had been signed with Motown. And I didn’t think that that was possible because no one had told me. And what happened is that Motown bought the company that I was with, which was Golden World, and because of that I became instantly a Motown artist.”

It wasn’t until after Edwin was at Motown for a while that he found out why Motown head Berry Gordy wanted to buy Golden World Records — and, more specifically, why Berry wanted to buy him:

“[Berry Gordy] bought me with the intentions of, I wrote a song that has been, and still is, one of his favorite songs. Which is ‘Oh How Happy.’ And he wanted the rights to that song. I never understood or knew the reasoning why at the time, but I eventually did find out what the story was.

“The Jackson 5 were just getting ready to do a cartoon series (below). The cartoon series was going to be worldwide distributed. He wanted to use ‘Oh How Happy’ as the theme song for their cartoon series. Well, they called me into the office and offered me a silly amount of money to sell them the rights to the song, and of course I walked out… That was one of the reasons it took me two-and-a-half years [of wrangling over the contract …].”

Edwin was no wet-behind-the-ears, new kid on the block in the music industry when Motown acquired him. “I started singing in 1955 with my first group, the [doo-wop] group called the Future Tones. We were the number one group in Ohio and Cleveland until I went into the army [in 1960].”

He was also an experienced and successful songwriter with a string of chart-making singles on the Ric-Tic Records label (twin to Golden World), with “Agent Double-O-Soul,” “Back Street,” and “Stop Her on Sight (S.O.S.)” all making the Top 40 on the Billboard R&B chart, and The Shades of Blue version of “Oh How Happy” reaching #12 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Which explains why his first few years at Motown were not the happiest or most productive for this talented singer-songwriter, who found one musical arm tied behind his back:

“When I was with Motown, they didn’t allow me to write. As far as they were concerned, I was purely and simply a singer, and that was it. End of story. And a singer with a direction that they didn’t know what to do with. OK? But when I was with Golden World, the first company that they bought me from, I wrote ‘Agent Double-O-Soul,’ ‘S.O.S.,’ ‘Headline News,’ ‘Back Street.’ I wrote all of that stuff and produced it. And then when I went to Motown, they wouldn’t let me write anything or produce anything.”

That didn’t mean that he didn’t worry for his career or honor his recording contract, however. Despite being involved in protracted ‘wrangling’ over that contract, he worked with different Motown producers doing lead singing duties on a steady parade of songs.

Most notably for our purposes here, he worked with the legendary Motown songwriter and producer Norman Whitfield on a number of love songs, including “I Want My Baby Back,” “Gonna Keep On Tryin’ Till I Win Your Love,” “My Weakness is You,” and “He Who Picks a Rose.”2

Edwin’s growing professional relationship with Norman boded well for his future, but it was actually a performance on a live TV show that turned around his fortunes at Motown and put him back on the hit-making track:

“So finally, I did a TV show called 20 Grand Live, and I didn’t have a closing number. So I did a song that I had written called ‘Twenty-Five Miles’ and the next day at the company, the telephones are ringing off the hook and people are saying ‘Where can I buy this song?’

“So the president at that time, Barney Ales (below right, with Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield), called me into his office and said ‘Where’s this song at? Where’s this song come from?’

“And I said, ‘I wrote it.’

“‘But,’ he said, ‘how come it hasn’t been recorded?’

“And I said, ‘I tried to record it, but they told me it was only a good rock and roll song.’

“It didn’t have no feet, you know. It wasn’t the type of thing that Motown was normally used to doing. Because they did crossover. Everything was pop-orientated, right? So finally they let me record that, and then that was the beginning of them letting me get involved with records again.”

That ‘only a good rock and roll song,’ “Twenty-Five Miles” (1969), turned out to be a huge hit in the US, Canada, and the UK, going to #6 on both the Pop (!) and R&B charts in the US.

It’s one of my favorite dance songs, so if you’re willing to take a quick detour from our story to groove to a great tune (it always makes me jump to my feet), here it is:

Despite its success, “Twenty-Five Miles” was not to be Edwin’s biggest hit, because Norman Whitfield was about to hand him an even bigger one — a protest song.

Dennis Coffey, a guitarist in Motown’s incredible backup band, the Funk Brothers, gives an insight into Norman’s role in putting Motown on the map with protest songs in an interview with Jeremy Shatan, author of AnEarful substack:

“‘He was doing these protest things. I used to see Norman in the clubs all the time. He was a very savvy guy that went out in the streets to hear what the people were reacting to.’”

What Norman was hearing was a growing sentiment against war and conflict reflected in popular music. And despite the fact that Motown was not known for rocking the boat, he moved quickly to translate that sentiment into not just one but a series of hit protest songs.

The first of these was “War,” co-written by Norman with his regular songwriting partner, Barrett Strong (see photo above video), and recorded with the Temptations for release on their Psychedelic Shack album in March 1970.

Edwin described what happened next:

“…about four thousand or five thousand college students wrote into the company and they said ‘You’ve got to release this record [as a single]. This record has got to be released because it’s pertinent to what’s going on today. So Motown at that particular time said, ‘Well, we can’t put it out on the Temptations, because it’s political dynamite. If it goes the wrong way, their career is gone.”

Norman Whitfield was on the side of the college students, fighting to have the song released as a single. But he was fighting against his own success, as the album Psychedelic Shack had become a #1 LP on the R&B chart and a #7 LP on the Pop chart — a success the company did not want to jeopardize by taking the risk of alienating the Temptations’ more conservative fans.

Instead, he was allowed to record his second protest song, the less incendiary “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World is Today),” with the Temptations and release that as a single just two months later, which was also a hit, going to #2 on the pop chart and #3 on the R&B chart. See my post on “Ball of Confusion” here.

As a further compromise, given his status as one of Motown’s most successful writers and producers, Norman was also given the go-ahead to release “War” as a single, but only if he had another artist re-record it.

That other artist turned out to be Edwin, after white rock band Rare Earth (below) turned it down. As interviewer Mark Stewart asked, “They weren’t worried about you? That wasn’t very nice.” (Especially since Edwin had just handed Motown a hit with “Twenty-Five Miles.”)

“Well, you know,” Edwin replied, “it was a situation where they literally did ask me if I want to do it, and I said ‘Of course I want to do it. You know, as long as I can do the vocal performance the way I want to do it.’ Because if you do a song like that, you can’t mollycoddle it. You gotta do it, you know. And I said, ‘I’ll do it, but I got to do it with the conviction that I feel.’ So they allowed me to do it.”

As he clarified later in the interview, “I’m not opposed to working with anyone. As long as they understand that I will stay true to who I am. I will not alienate what it is that I do. I sing funk and soul, and that’s what I do.”

What’s ironic about Edwin being asked to sing this song is that he was a military brat, his father having been a career soldier who attained the rank of Sergeant Major. Edwin himself volunteered for the draft in 1960, a way to serve for only two years as opposed to the three required of involuntary inductees. But his military service was extended for an additional year when President Kennedy imposed a mandatory extension of one year for everyone, resulting in Edwin serving in Germany until 1963.

Yet — even while in the army — Edwin found a way to continue to ply his musical trade, performing in Berlin and Amsterdam when he went on furlough.

The reason he may have agreed to do “War,” despite his military background, was that he didn’t view it as an anti-war protest song:

“The misunderstanding about the song ‘War’ is that the song was never supposed to be about the Vietnam War. What they were simply writing about, was about the conflicts that people were facing on a day-to-day basis in the United States at the same time with all the riots and things.”

Hmm, I’m not sure I agree when I read the lyrics. It sure does seem to be anti-war. What do you think?

“They never ever did anything with the record as far as promotion is concerned,” Edwin also noted, most likely because pent-up demand among college students had already been created by the Temptations version. “The record was already gold before they did the first promotions on it.”

As Motown boss Berry Gordy observed in his autobiography, To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown, “‘War,’ with Edwin’s thundering vocals and Norman’s raging tracks, charged up to #1 and became almost an anthem of the times — voicing the deep antiwar feelings of a growing number of people.”

Another factor in its success, to my mind, is the personal commentary that Edwin added to the song: “‘Good God y’all’ and all those ‘Absolutely nothings’ are my ad-libs.”3 His additions grabbed attention and made it one of those songs you had to sing along to.

The single remained at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for three weeks, and also reached #3 on the R&B chart. The song pushed Edwin’s War and Peace album (produced by Norman) to #52 on the US album chart and #9 on the R&B album chart.

Edwin was also nominated for a Grammy for Best R&B Vocal Performance Male (losing out to B.B. King’s “The Thrill is Gone”).

The single eventually went double platinum and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1997. But for some reason, Motown almost didn’t give Edwin his platinum record:

“That was the funniest thing about it… The record went double platinum, and the way they gave me my platinum record is that one day I was walking through the company, walking down the hallways, and one of the secretaries said, ‘Hey, Edwin! I got a record for you over here in the corner if you want it. You can come pick it up when you get a chance.’ I mean —”

“Double platinum, here you go,” interviewer Mark Stewart interjects.

“Yeah,” Edwin laughs. “Here you go.”

Motown may not have treated Edwin like a valued asset, but Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong indisuptably did, asking him to do another album that included both “War” and a third protest song, “Stop the War Now.”

Edwin thought “War” had been strong enough and the end to the Vietnam War was inevitable, but he agreed to record “Stop the War Now” just the same.

Smart thing that he did, as “Stop the War Now” turned out to be another hit, going to #5 on the R&B chart and #26 on the pop chart, and, paired with “War,” took the album, called Involved, to #45 on the R&B album chart.

Music critic for the Village Voice Robert Christgau considered the album Involved to be “Norman Whitfield's peak production.”4

One of the factors contributing to the success of both albums was the quality of the backup singers Norman recruited. For War & Peace, it was two groups — The Originals and The Undisputed Truth. For Involved, it was Total Concept Unlimited, a group that served as the studio and concert band behind the Undisputed Truth and later became Rose Royce (below), which scored a string of hit singles, including “Car Wash,” “I Wanna Get Next to You,” “I'm Going Down,” “Wishing on a Star,” and “Love Don't Live Here Anymore.”

Total Concept Limited would tour Europe and Japan with Edwin in 1973, while he was still with Motown. (He left in 1975.)

Among a number of covers of “War,” one was performed by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band in their Born in the U.S.A. Tour in 1985 and included in his box set Live/1975–85. Released as a single, that version of the song also became a hit, going to #8 in the Billboard Hot 100.

Bruce included the song in many of his tours, including in the early days of the Iraq War, and performed it with Edwin during a show on the Reunion Tour. I wished I had been there — what a performance, which you can watch here.

But you can’t miss Edwin’s original version, produced by Norman Whitfield, which has become absolutely iconic among anti-war songs. You can listen at the top of the post, or watch Edwin below.

Song credits

Songwriter - Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong

Producer - Norman Whitfield

Lead vocals - Edwin Starr

Background vocals - The Originals (Freddie Gorman, Walter Gaines, C. P. Spencer, and Hank Dixon) and The Undisputed Truth (Joe "Pep" Harris, Billie Rae Calvin, and Brenda Joyce Evans)

Instrumentation - The Funk Brothers

Arrangements (album) - David Van De Pitte, Henry Cosby, Paul Riser, Wade Marcus and Willie Shorter

All quotes are from Mark Stewart’s interview with Edwin Starr unless otherwise indicated.

Chancellor of Soul’s Soul Fact Show Edwin Starr Story Part 2.

Classic Motown Track of the Week: Edwin Starr - “War.” https://classic.motown.com/story/edwin-starr-war/.

Quote from Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: S". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Lifted from Wikipedia, September 28, 2024.

Even the name "Edwin Starr" was forced upon him. His real name was Charles Hatcher, but, when he was performing with Bill Doggett's group, he was introduced one night as "Edwin Starr", without being consulted first, and that was that.

He was an amazing singer- at Golden World he cut three stone classics, "Stop Her On Sight (S.O.S.), "Headline News" and "Agent Double O Soul", and you can clearly hear why Gordy wanted him so badly. But "War"- my God! He was in full Baptist preacher mode on that- not so much singing the lyrics as SCREAMING them with an insane amount of passion. He sold the song to an even greater degree than even Whitfield must have imagined- and it was no wonder it ended up as a #1 hit.

And, of course, it's still relevant now, because war still "ain't nothing but a heartbreak" and "friend only to the undertaker".

Probably the most OG of the anti war songs. I had to smile at the thought he didn’t view it as an anti Vietnam song. I suspect that’s his narrative for the press to consume. Who knows, maybe he did actually believe it in some way.

I don’t know if this is on your list somewhere but Two Tribes from Frankie Goes To Hollywood is probably one of the better known anti war vids from the start of the MTV era.