"What's Going On" by Marvin Gaye (1971)

My favorite protest songs of the 60s and early 70s

Welcome, everyone, to the thirteenth post in this series about my favorite protest songs from the sixties and early seventies.

If you’re new, here’s a list (with links) of what we’ve covered so far:

“Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan (1963)

“Masters of War” by Judy Collins (1963)

“Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire (1965)

“For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What’s That Sound)” by Buffalo Springfield (1966)

“Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones (1969)

“Sweet Cherry Wine” by Tommy James & the Shondells (1969)

“Give Peace a Chance” by the Plastic Ono Band (1969)

“Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell (1970)

“Ball of Confusion (That's What the World Is Today)” by the Temptations (1970)

“Ohio” by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (1970)

“War” by Edwin Starr (1970)

“Signs” by the Five Man Electrical Band (1971).

Other substackers have also offered their own interesting takes:

Mick McJesus of Mick’s Substack put together a playlist of about 140 protest songs

NickS asked “What makes a good protest song?” and gave his own list of favorites

Jackie R shared a song that makes fun of protest songs

David Drayer explained the Australian protest song “Waltzing Mathilda.”

Next up will be a list of honorable mentions, and I’ll end the series with a summary post about what this motley collection of protest songs appears to tell us.

Today we focus on a song that expressed a common sentiment at that time — “It’s not cool, what’s going on” — by an artist chafing to restore freedom and integrity in his own life and, even more urgently, in the conduct of his nation and — dare he dream it? yes, he did — by humankind in general.

Protest song of the day

In 1970, Marvin Gaye was in the enviable position of being Motown’s bestselling male artist and its premier sex symbol, and yet, for a year, he’d had no motivation to go on. Instead, he’d been hanging around at home getting high and fighting with his wife, Anna Gordy Gaye (below), Marvin’s sometime songwriting collaborator as well as a former record executive and one of Motown head Berry Gordy’s older sisters.

Marvin had yet to establish a solid reputation beyond that of “a Motown stooge with a flair for interpreting ready-made hits,”1 unlike his Motown peers such as Smokey Robinson and even the teenage Stevie Wonder, who were trusted with writing and producing their own songs.

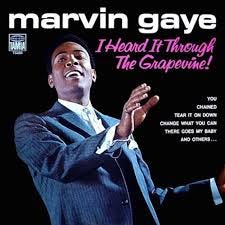

The “Prince of Motown,” as Marvin was called, had earned acclaim for his 1968 international hit and eventual soul classic, “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” but didn’t feel that he’d earned that success. Gladys Knight and the Pips had already had a hit with the same song earlier that year, and Marvin had not had a good experience with the song’s co-writer and producer Norman Whitfield, who had pushed him to sing beyond his range and had also overdubbed some of his vocals with those of a Motown backup group, the Andantes.

Even worse, Marvin had never enjoyed performing live, and that was especially true now that his long-time recording and singing partner and close friend, Tammi Terrell, had collapsed in his arms onstage and been diagnosed with a brain tumor. Tammi had reportedly suffered beatings by James Brown while serving as his backup vocalist and had complained of severe headaches.2 Her series of unsuccessful surgeries and hospitalizations hit Marvin hard, as had her recent death in March at the criminally young age of 24.

As if that weren’t all enough, he wondered how he could continue to sing love songs in the face of all the problems in the world. “When my brother Frankie came home from Vietnam and began telling me stories,” he told his biographer David Ritz, “my blood started to boil. I knew I had something — an anger, an energy, an artistic point of view.”3

He reasoned, why shouldn’t he give his point of view when so many artists were expressing their views on social and political issues, many of them black artists such as Curtis Mayfield with the Impressions, the O’Jays, War, the Staple Singers, Sly and the Family Stone, and even some Motown acts like Martha and the Vandellas and the Temptations?

Soon after Tammi’s funeral a propitious opportunity fell right into his lap when Renaldo “Obie” Benson (second from left below), the bass singer in the Motown group the Four Tops, came to Marvin with a song he’d composed with songwriter Al Cleveland and suggested that Marvin consider recording it.

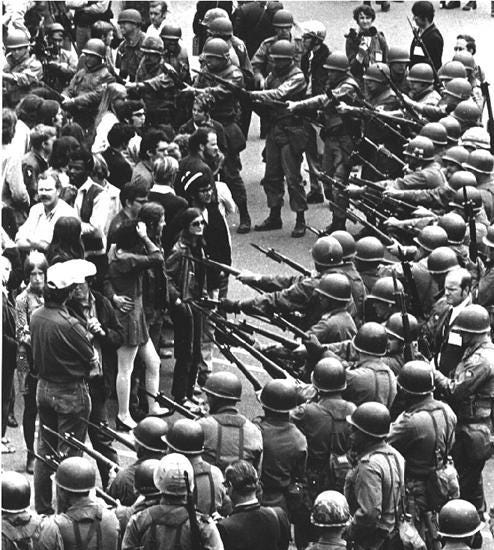

The song had come about after Obie visited Berkeley, California with the Tops on May 15, 1969 and witnessed police brutality towards anti-war activists (mostly Berkeley students) protesting in People’s Park, a day that came to be called “Bloody Thursday.” (One bystander sitting on a roof was shot and killed, and dozens of protesters and police were wounded. Note that this was before Kent State and Jackson State, as laid out in my previous post on the CSN&Y song “Ohio”.)

The violence upset Obie and raised questions in his mind: “What is happening here?… Why are they sending kids so far away from their families overseas? Why are they attacking their own children in the streets?”4

Obie had already peddled the tune to his fellow Four Tops and been turned down. “My partners told me it was a protest song… I said, ‘no man, it’s a love song, about love and understanding. I’m not protesting, I want to know what’s going on.’”5

Joan Baez had also turned it down, and Marvin’s initial reaction was the same. But Marvin had been mastering the art of production with a Motown male quartet he’d taken under his wing called the Originals. Their 1969 hit on the Black Singles (#1) and Pop Singles (#14) charts, “Baby I’m for Real,” was co-written and produced by Marvin. He thought the moody vibe to Obie’s tune might be perfect for them.

Marvin went to work revising the song, adding a new melody and some of his own lyrics, and giving it a title, “What’s Going on.” As Obie later noted, Marvin “added some things that were more ghetto, more natural, which made it seem more like a story than a song… we measured him for the suit and he tailored the hell out of it.”6

At some point, Obie convinced Marvin that he should do the song himself rather than giving it to the Originals.

It was not a hard sell. Marvin was ready to translate his mounting frustrations at the state of his professional career and the state of the world into concrete action, and he’d already proved his production chops with the Originals hit. “I understood musically that I’d have to go on a path of my own… The Motown corporate attitude didn’t give me much room to breathe, but I was starting to feel strong enough to start down my own path.”7

As Berry Gordy relates in his memoir,8 Marvin called while Berry was vacationing in the Bahamas to tell him that he wanted to make a protest album. Berry was not amused, Marvin having accomplished nothing expected from him for a year. Berry recalled the conversation as follows:

“Protest about what?” he asked Marvin.

“Vietnam, police brutality, social conditions, a lot of stuff.”

“Marvin, don’t be ridiculous. That’s taking things too far.”

“I’m not happy with the world. I’m angry. I have to sing about that, I have to protest.”

“Marvin, this is crazy. Stick to what you do. Stick to what’s happening. Stick to what works!”

“Stick to what works? Come on, BG. You’ve never done that in your life. You’ve always done something different.”

“But I am never different just for the sake of being different. It has to mean something positive. If you’re going to do something different at least make it commercial… Marvin, you’ve got this great, sexy image and you’ve got to protect it.”

“I don’t care about image, BG. I just gotta do it. You’ve got to let me do this. I want to awaken the minds of mankind.”

“Marvin, we learn from everything. That’s what life is about. I don’t think you’re right, but if you really want to do it, do it. And if it doesn’t work you’ll learn something; and if it does I’ll learn something.”

That last statement by Mister Gordy is, according to sources, open to dispute. Berry didn’t want to back “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” (below), which had been a smash hit, and he didn’t want to support What’s Going On — in the same commercially baffling way he hadn’t wanted to support Edwin Starr’s career or Norman Whitfield’s desire to produce protest songs. (See my previous post on the song “War.”)

Deliberately flouting Berry’s wishes and Motown rules, Marvin went ahead anyway and scheduled the first session at Hitsville USA to record the backing track and overdubs for “What’s Going On,” on June 1, 1970. He later used Studio B to add lead and background vocals and strings and horns.

Relatively new to being a producer and without the usual Motown supervision, he went ahead and did it his way, unhampered by the standard studio protocols and expectations.

Similar to Carole King’s approach when making her mega-selling album Tapestry, Marvin invited only those he knew and trusted to help him realize his vision.

These included members of the Funk Brothers, the in-house studio musicians, as well as other non-Motown musicians he knew (Eli Fountain and Chet Forest), disrupting the normal set-up and pushing people out of their established routines.

He also invited friends of his from the Detroit Lions football team, Mel Farr and Lem Barney (below), as well as Bobby Rogers of the Miracles and musician and songwriter Elgie Stover, to provide mock chatter to make it sound like a party at the beginning and at different points throughout the song: “Hey, man, what’s happening?” and “Right on” and so on and so forth.

With marijuana smoke suffusing the air, the ambiance in the studio was relaxed and loose, allowing a stream of happy accidents to occur. With the tape already running, Eli Fontaine warmed up his sax by improvising a riff that Marvin considered so perfect, he told him his work was done and he could go home. Eli protested that he was just “goofing around,” and Marvin told him “you goof off exquisitely, thank you”9 and sent him on his way, an opening riff neatly in the bag.

Legendary bassist James Jamerson (below right, with Marvin) almost didn’t make the session, Marvin rousting him from a local bar where he was playing and already “smashed” on Metaxa. Unable to play sitting up, James nevertheless nailed his part while lying on the floor.

Arranger and conductor David Van De Pitte, working closely with Marvin, had written the part expressly for him, and James played it exactly as written. As David later recalled, “He loved it because I had written Jamerson licks for Jamerson.” Even in the state he was in James knew, as he told his wife Annie when he got home, that they had produced nothing less than a “masterpiece.”

Another happy accident occurred when Marvin asked engineer Kenneth Sands to give him two versions of his vocals to compare, and by accident Kenneth mixed the leads together creating a double layer of Marvin’s voice. Marvin not only kept the double-track version but continued to use multi-layering of his voice in future recordings.

Other elements of the production were equally ground-breaking. Marvin used a hand-held mike and wandered around the studio as he did his vocals, as if he were onstage and playing to an audience, and also added his own instrumentation with piano, keyboards, and a box drum to accentuate Chet’s drums. The song was a blend of soul, jazz, and psychedelia, and used major seventh and minor seventh chords in a way that was unusual at that time. Marvin also gave the song a false fade at the end, bringing it back for a few seconds after it seemed to be over.

When Marvin presented the song to Berry Gordy, and later when head of A&R Harry Balk asked for permission to release it, Berry tried to shelve it, calling it “the worst piece of crap I ever heard” and “that Dizzy Gillespie shit,” saying “that scatting, it’s old.” On a different note, he claimed that it was too different and too political to be released by Motown.

Marvin responded by going on strike and refusing to record another note for the company until the song was released. Balk also wasn’t having it, convincing sales vice president Barney Ales to press 100,000 copies and promote the song to radio stations across the U.S. without Berry’s approval.

Released in January 1971, 200,000 copies of the single were snapped up within a single week. By March the song reached #1 on the Billboard R&B/Hot Soul Singles and the Cash Box Top 100 charts, and #2 on the Hot 100. It was ranked the #21 song for the year. The song eventually went double platinum.

Beyond sales, the song has attained status as a both a classic and a song with enduring popularity, significance, and influence. It was:

nominated for two Grammy awards, for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance and Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist(s)

included in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll (1995)

among the Top 10 most-streamed Motown songs worldwide

#4 in the Rolling Stone’s Greatest Songs of All Time in both 2004 and 2010, Marvin’s highest song on the list

#14 on VH1’s 100 Greatest Rock Songs of All Time (2000)

#65 on Recording Industry Association of America’s 365 Songs of the Century (2001)

#33 on New Musical Express’s Greatest 1970s Songs (2012)

#2 in “Detroit’s 100 Greatest Songs” based on voting conducted by the Detroit Free Press with music experts and the public (2016)

#1 on Detroit’s Metro Times list of the “Greatest Detroit Song of All Time” (2004)

#74 on BBC Radio 2’s Songs of the Century (1999)

#64 on Q Magazine’s 1001 Best Songs Ever (2003)

covered by a wide array of artists across genres from 1971 to today, with 100 covers alone listed here.

There’s no arguing with commercial success, and not only was Berry Gordy satisfied with the single’s sales, he wanted an entire album, and he wanted it by the end of March.

Marvin was only too happy to comply, producing a concept album from the point of view of a Vietnam veteran returning home from the war only to discover that an unexpected range of political, economic, social, and environmental issues were creating rifts in families and communities and shattering his beloved country.

The album was groundbreaking in sustaining a mood and a rhythm across the songs that seduced the listener with a party-like atmosphere and a jazz-like sensuality only to unsettle them with the urgency of the themes and the lyrics.

It was also groundbreaking in, finally, giving public credit on the record itself to the Motown artists behind the scenes who’d made significant contributions to the recording, namely David Van De Pitte and the Funk Brothers.

The album was a commercial and critical success, and produced two more Top 10 pop singles — “Mercy Mercy Me” and “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler).” In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked the album at the very top — #1 — on its list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

As Berry Gordy admitted in his autobiography, the album was “a major smash” and, contrary to his alarmist predictions, the “Prince of Motown” remained as sexy as ever. (What he didn’t remain for much longer was his son-in-law.)

Herewith is the song, “What’s Going On,” from an artist who aspired to “become an impeccable warrior… only interested in knowledge and power that this earth will give us, if we’re only willing to put in the time and effort… that knowledge and that power that the truly gifted sorcerer has. The power’s here — it’s in the rocks, it’s in the air, it’s in the animals.”10

Methinks Marvin succeeded. See what you think.

Song credits

Musicians:

Marvin Gaye – lead and backing vocals, piano and box drum

Backing vocals by Marvin Gaye, Mel Farr, Lem Barney, Elgie Stover, Kenneth Stover, Bobby Rogers, and the Funk Brothers

Instrumentation by the Funk Brothers and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra including:

Eli Fountain – alto saxophone

Robert White – acoustic guitar

Joe Messina – electric guitar

James Jamerson – bass

Chet Forest – drums

Jack Ashford – tambourine, percussion

Production and composition:

Marvin Gaye – producer, composer

Renaldo "Obie" Benson – composer

Al Cleveland – composer

David Van De Pitte – arranger

Steve Smith – recording engineer

Mike McLean – recording engineer

Ken Sands – recording and mix engineer

The NME Rock ‘n’ Roll Years, Reed International Books Ltd, 1990, p. 294.

The History of Rock & Roll: Volume II 1964-1977, Ed Ward, 2019.

From https://classic.motown.com/story/marvin-gaye-whats-going-on/.

Edmonds, Ben (2003). Marvin Gaye: What's Going On and the Last Days of the Motown Sound (book). Canongate U.S. as quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What's_Going_On_(song)#cite_note-FOOTNOTELynskey2011155-8.

Lynskey, Dorian (2011). 33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day. HarperCollins. As quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What's_Going_On_(song)#cite_note-FOOTNOTELynskey2011155-8.

See footnote 5.

From https://classic.motown.com/story/marvin-gaye-whats-going-on/.

To Be Loved by Berry Gordy (1994).

See footnote 5.

Which Side Are You On: 20th Century American History in 100 Protest Songs, James Sullivan, 2019.

Marvin constantly shortchanged his own abilities throughout his career, but the work he left behind belies all of his modesty. The album and the single came at the right place and the right time, and they still matter- "Mercy Mercy Me" and "Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)" have more relevance now than ever.

He'd continue to score with great songs and albums up until his death- "Let's Get It On", the "Trouble Man" soundtrack, "I Want You", "Here, My Dear" (about the end of his relationship with Anna Gordy) and "Midnight Love" (with "Sexual Healing"). His revelatory and unforgettably emotional singing, both as the so-called "stooge" of the 60s and in these albums, was especially what turned him into my favorite singer of all time. No one can touch him for being purely and emotionally honest, and you hear that clear as day on "What's Going On?".

Congratulations! You may have solved a music mystery for me. I distinctly remember my 11th grade black dance/drama teacher named Debbie improvising an breathtaking dance to this song circa spring semester 1970, on the stage of the Berkeley Community Theatre where the class was held. But…album released 1971! In revealing that composer Obie Benson was at People’s Park riots in May 1969, it is entirely possible that he *somehow* gave her a copy. At least that’s what I now can believe. That’s a detail I did not know before. Of course it may have been Mercy Mercy Me instead. But the breathtaking dance did happen . . . We got home on the bus passing the tear gas on Telegraph Avenue. Good times!