Where have all the protest songs gone? Is something stopping artists from writing or singing them?

The protest song series

Welcome, everyone, to part 2 of our final post in the protest song series.

In case you’re new or missed anything, here are the latest posts in this series (you can access the earlier posts through the second humor post):

Where have all the protest songs gone? Have artists lost interest? (Part 1)

Humor about protest songs from four brilliant comedians

‘Personal’ protest songs by 10 artists

Favorite protest songs of 25 Substack authors passionate about music

A guest post by Kev Nixon on John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero”

“The Want of a Nail” by Todd Rundgren: Is THIS a protest song?

The strange and supernatural events behind “Eve of Destruction”

What, exactly, is a protest song? And which songs qualify for this revered category?

We’ve been ending the series with a question raised in a post by Sean Johnson, which is “where are all the new protest songs at?”

He noticed that “there aren’t as many protest songs or songs that immediately speak to the zeitgeist as there used to be. In our turbulent and bat shit crazy times, I would think there would be a glut of these songs, but as far as I can see, there aren’t many if at all…”

To answer this question, we have to think about two things:

Which artists are most likely to write, record, and perform protest music, and do we still have those kinds of artists?

Historically, only a small proportion of artists have chosen to put out protest music and have succeeded at it. Who are those people?

I offered one way of thinking about that question in Part 1, and concluded that those kinds of artists do indeed still exist — protest is what we do as human beings, with artists often being the proverbial canary in the coal mine alerting us to threats and danger — but something is preventing protest music from either being created or, alternatively, from reaching a wider audience.

Hence, the second question that we address today:

What conditions enable artists to write, record, and perform protest music, and what conditions prevent it?

Part of that will be answering Sean’s question. Where are all the protest songs, goldarnit? Shouldn’t there be a lot more?

Our theme song continues to be “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane, but this week we will be chasing rabbits down holes, swallowing some bitter pills, and feeding our heads. No holding back.

Our featured artist is Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway playing “White Rabbit” live and with multiple string instruments (video above).1 Marvelous.

Paid and founding member subscribers will also be receiving Part 3 about conspiracy theories that provide alternative explanations for what’s happened to protest songs.

We will then move on to the new series on Women in Rock. I’m already deep into research on our first fascinating artist, Janis Joplin.

When the Red Queen’s ‘Off with her head!’

In explaining what’s happened to protest songs, we’re going to look at three layers:

major changes in the culture and operation of society

the evolution of the music industry

the pressures and conditions faced by artists

We’re contending with a large, complex system here and, without question, there are many other ways to look at this. So please see the theories and possible explanations I offer below as something to consider, not as a be-all-and-end-all answer.

Too much lovin’ breeds little monsters

Taking a big picture view, we can look at history over long sweeps of time and identify trends that seem to recur at predictable intervals.

One such trend identified by psychologists is that when you have a surge in fertility rates in a population, i.e., a lot of good lovin’ going on, about 25 years later you’re going to see a generation of frustrated revolutionaries pop up and start making waves.

In other words, there’s too many of them, they’re inciting one another, and the little monsters are running amok.

A prime example happened in the sixties and early seventies in the U.S. when the Baby Boomer generation came of age. That surge in procreation happened in the mid to late forties as soldiers returned from World War 2 and invested in settling down and creating families.

If you were raised in the sixties, as I was, there were kids everywhere and we were a force to contend with as we drove pop culture and commercial trends. Who made the Beatles, the Stones, and the Monkees household names? We did.

But we were also a force to contend with in terms of social and political issues — protesting against the Vietnam War and in favor of civil rights and women’s liberation.

What especially provokes civil unrest among youth, according to psychologists, is frustration of their ability to live the life they expect to live. Which is what we saw with young men being sent off to sacrifice their lives in Vietnam, and young women seeing their male family members and potential life partners being taken away from them. We also saw minorities and women pushing to have better life choices and life chances and not be stifled by the constrictions of a more traditional mainstream culture.

Such civil unrest, of course, spills over into creative pursuits, leaving “an imprint on a nation’s literature, arts, and music.”2

Hence we see a concentration of protest music in a time like this, not only because we have a boom in frustrated and outspoken young people, but also because we have safety in numbers and a social learning effect.

As we saw in this series, singers were not jumping to become protest singers unless they were identified with folk music, a niche with a long and hallowed history of social and political protest. Anyone who wanted mainstream commercial appeal avoided being identified as a protest singer — witness Bob Dylan’s vociferous denial — until the door was opened by some early risk-takers like Barry McGuire, who lost his rock ’n’ roll career as a result of “Eve of Destruction,” and Buffalo Springfield, who confined themselves to singing with an air of perplexity about an incident on the Sunset Strip in Stephen Still’s “For What It’s Worth.”3

Watching what happened to these early protest songs, artists proceeded carefully. We saw protest songs disguised as bog standard pop tunes, like “Sweet Cherry Wine” by Tommy James and the Shondells, or as appeals to “love one another” or be happy people, rather than coming out and openly advocating against discrimination or war.

What broke it wide open, in my view, and resulted in a deluge of anti-war activities and blatant protest songs was the unexpected and horrific killing of students at Kent State, and, no question, the agreement and support of Atlantic label head Ahmet Ertugun to rush out the Crosby Stills Nash & Young song “Ohio” that called out the Nixon Administration for perpetrating this senseless murder.

Record labels were not normally supportive of protest music given their reliance on radio stations regulated by the government. But, as we will discuss in Part 3 on conspiracy theories, Crosby Stills Nash & Young were not just any group. Two members were not American and could return back to their own countries if need be — Englishman Graham Nash and Canadian Neil Young, who penned the song — and the other two members were ‘protected’ by their unusual backgrounds, David Crosby coming from a prominent blue blood family and Stephen Stills from a covert military background. The risks to the members of this supergroup were not what they were to others, including the Temptations, prohibited by Berry Gordy at Motown from releasing “War” as a single because as a black supergroup their commercial success (and safety?) was far more vulnerable.

In line with the ramped-up anti-war zeitgeist in the early seventies, we saw limited release of protest songs by intrepid and insistent producers like Norman Whitfield, who talked Motown into releasing the single of “War” performed by an artist whose career Gordy did not care about, Edwin Starr.4 Or Marvin Gaye blackmailing Gordy into allowing him to make his protest album What’s Going On.

But we still saw most commercial labels, producers, and artists being careful. Even John Lennon, one of the most famous and popular musicians in the world, pulled his punches and exhorted us to “Imagine” a world of peace (following his song “Give Peace a Chance.”) After all, Lennon was on the FBI’s watch list and denied entry to the U.S.

The momentum went out of the various sixties protest movements with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the end of the Vietnam War, and the influx of women into institutions and careers formerly barred to them. Now what were they going to protest?

But it was also the case that the Baby Boom generation followed another demographic trend, which is that people become more conservative as they get older and “former radicals become co-opted by the establishment.”

John Lennon became a house-husband, Edwin Starr put out disco hits, Crosby Stills Nash & Young split up and for the most part went their separate ways, and Marvin Gaye sang about “Sexual Healing.” Life goes on.

We have not experienced a baby boom of that ilk in the U.S. since, and, according to this theory, we would not see the same concentration of protest songs until one occurs.

What this doesn’t explain is the rise of punk music, the grunge movement, hip-hop, and rap, nor as far as I can tell the jazz and the blues, all of which are identified with protest against the Establishment in one form or another. The French Revolution, like the sixties counterculture, is nicely explained by this theory, but we will need to look further for a more encompassing explanation.

Ooh, that cultural water is too hot

The highest-ranked music substack is Ted Gioia’s The Honest Broker, and Ted has quite an interesting theory about the historical eras that define culture, one that I think is interesting and relevant to our discussion.

It’s worth mentioning that Ted is a music historian and has written on the social history of music, including books on Work Songs, Healing Songs, and Love Songs. It’s also worth mentioning that, as an independent writer, he thinks outside the box and doesn’t hesitate to come up with his own theories, which are often quite provocative.

In a recent post, he repeated his contention laid out in his book The Birth (and Death) of the Cool that history follows a pattern of swinging back and forth between ‘hot’ eras and ‘cool’ eras every 40 to 50 years.

From World War II until 9/11 we were in a cool era, and since 9/11 we’ve been in a hot era. Like, what?

As Ted explains, “In 2009, I predicted that the next 20 years, more or less, would be a time of seething rage and relentless social conflict. The cool laid-back communication styles of the past would disappear. Instead, public discourse would be blunt and confrontational.”

Applying that to our topic of protest songs, the question seems obvious. In a time when everyone is loudly and forcefully giving their opinion — on social media, in blogs, on websites, and in person — what would be the point of a protest song?

That’s just your opinion, listeners would growl. You’re just putting your opinion to music. Who cares? Nice tune, but what I think is…

Unless, of course, they agree with the sentiment of your song, in which case they will recommend it to everyone they know, or anyone subscribing to their blog or substack.

As happened with popular music blogger Bob Lefsetz, who wrote about Jesse Welles’ recent protest songs when they were brought to his attention by his readers, or Substack author James Roguski recommending the music of Kelly Newton-Wordsworth to “help awaken the world.”

There’s also the example (thanks, NickS!) of Oliver Anthony’s protest song “Rich Men North of Richmond” becoming a hit, which went viral on social media and jumped to the top of the Billboard and streaming charts because Oliver struck a chord with his articulation of the concerns of a working class fed up with “bullshit pay,” “nothing to eat,” “dollar ain't shit,” and other social ills.

So protest songs are, indeed, still being made, and in some cases like these making the rounds and managing to get an audience, but their traction appears to be predominantly among the already converted. In other words, among those who share the artist’s beef with the world.

As Ted Gioia notes, “The Age of Cool was already losing momentum in the 1990s” with the rise of an ‘argument culture’ identified by Deborah Tannen in her late 90s book of that same name.5 But of course, one of the biggest factors in the death of the cool and the birth of the hot was the rise of the internet and the power it gave virtually everyone to make their opinions known with a few keystrokes and the click of an icon.

Before that, in the Age of Cool when artists could still have a voice and exercise some influence over public perceptions and opinions, we saw protest songs having local or even national and international impacts, as with those songs that helped to bring down apartheid in South Africa. (Link to my post on this below.)

How three artists — Peter Gabriel, Stevie Wonder, and Little Steven — helped bring down apartheid and inspired others

Welcome, everyone, to another post in the protest song series.

As we’ll see when we look at the evolution of the music industry, there were also a number of key developments that took away the power of the artist to have a real voice and influence.

Will artists like Peter Gabriel, Stevie Wonder, and Little Steven ever have that kind of power again?

Ted Gioia predicts that, maybe by 2030, maybe sooner, “the anger and brutality will soon diminish. Cool will come back. People will stop shouting and start speaking again… This happens because people eventually burn out on anger. You can only scream for so long. It feels good for a while. You take pleasure in your self-righteousness. You pride yourself on indignation. You love throwing punches.”

The question is therefore not whether people will get tired of shouting their opinions into the void or preaching to the already converted and will actually start to listen and be willing to discuss with those holding divergent opinions. It seems that they will.

The critical question is, rather, whether artists will be in a position to be heard and to have influence, as they did during the previous Age of Cool.

Let’s look at the industry and the dire plight of our artists. They are not likely to have any real and significance influence, despite the historically invaluable role of artists down through history, if things don’t dramatically change.

It would be a huge loss to society, and to us, if they don’t.

Yearning for a rock ‘n’ roll Camelot?

I was struggling with how to summarize the evolution of the music industry from the inception of rock ’n’ roll to what we have today — how to even approach that?! —when the universe started bombarding me with a river of information.

It was like a psychic call-and-response. Bob Lefseth, Steve Albini, Steven Tyler and Carter Alan, Pharrell Williams, Ted Gioia, and some fellow Substack writers who I acknowledge below came to the rescue. They will probably never know they did so, but I am remarkably grateful for the knowledge and insight they imparted to me through their writings.

Bob Lefsetz’s blog is something you should be reading even if you don’t agree with his politics, just for his voluminous knowledge on the music and entertainment industries. In a recent post he gave an overview of how the music industry evolved. Shazam!

You can read his entire post here, which I recommend, but allow me to summarize. Here we go.

In the folk music era, artists of course, like anyone, preferred to get paid, but they would show up anywhere for the cause even when they didn’t. They were innovators, crafting the music and message to speak to the hearts and minds of their audience about the issues they cared about.

As Bob notes, “back in the day, in the sixties, you’d be stunned how few albums some of the legends sold… Music blew up as a result of freethinking individuals putting it all on the line, not holding back punches.”

Most notable were the Beatles, who came, conquered, and created a tsunami of demand that professionalized the music business. But the industry, beguiled by the mountains of cash they were raking in (from the baby boomers), started to play it safe in the 70s with “corporate rock and mindless disco” that catered to the lowest common denominator and ended up crashing the business.

It took MTV in the 80s and music videos with flashy hair bands (and Michael Jackson and Madonna) to revive it, but the industry crashed the business again in the 90s by turning MTV into television with non-music shows, and also failed to capitalize on the excitement generated by indie rock (including grunge) and rap.

Enter Napster at the end of the decade giving consumers whatever they wanted whenever they wanted at no to little cost, with the music industry flummoxed as to how to respond to this threat and slow to react.

Within ten years, Spotify and other platforms had succeeded in consolidating and entrenching a music streaming culture that transformed music into an online digital product — bits and bytes — rather than a creative act of performance in the moment or a recorded and preserved product that allowed customers repeated access, listening, and enjoyment in a hard or soft storage medium. (Customers became ‘users’ instead.)

As part of this song-focused new digital era came singing competition shows that gave a platform to people who wanted to become instant musical artists — and a ‘brand’ — without investing the time, money, and commitment necessary to develop a bedrock of songwriting and performing experience and mastery honed through practice in front of countless audiences.

In this ecosystem, as Bob says, “the music is no longer the end result, but just a means to become a brand… It’s more like General Mills than the Beatles.” There is no longer any innovation, any backbone, or any social consciousness.

Instead, there is a “public that has stolen the power of music” with its demand for immediacy (and cheapness), being serviced by a younger entitled generation that operates like “cottage industries trying to get rich,” in an environment where “it’s harder than ever to make a living period, never mind in music. So those who might have been innovative and testing boundaries are in other fields. They just don’t want to take the risk of being broke.”

There is so much in Bob’s explanation here to explore and expand upon. Let’s turn first to that watershed decade when everything changed — the nineties.

Where have all the flowers like WBCN gone?

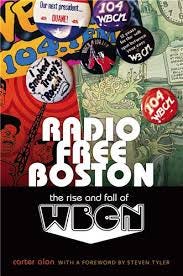

“Imagine a time when you could get good in a band by practicing in a basement or garage,” Aerosmith frontman Steven Tyler writes in the forward to Radio Free Boston: The Rise and Fall of WBCN6, “when you could play in local bars or clubs, and when local radio stations were actually running themselves. Real human personalities owned the music as much as the bands that wrote it; they frequented the clubs, knew personally the pulse of local talent, and knew the goings-on of a community or city. This, in fact, is how everyone from Willy Dixon to Elvis, the Beatles, the Beastie Boys, Run DMC, and a little unknown band from Boston called Aerosmith got their foot in the door… Due to the passion of these local DJs, we were able to ignite a fire that would burn in the heart of millions…”

As we learned in this series, a local radio station could break a song and make it popular by adding it to its playlist and igniting demand through word-of-mouth. “Eve of Destruction” and “War” both became hits as a result of extensive radio play, as did albums like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On.

Radio stations were an important gatekeeper in the industry, deciding what got airplay and what didn’t, but the difference until the late 90s was that the radio industry was a motley collection of independent stations staffed by a bunch of iconoclasts who decided what music they wanted to play. If they loved the debut album Facelift of this new Seattle group called Alice in Chains, and considered it of artistic or commercial merit and wanted their audience to hear it, they had the freedom and wherewithal to play the whole damn thing. If you didn’t agree with that decision, too bad.

WCBN was one of the gleaming jewels in the national radio crown, and as a DJ and music director for the Boston station from 1979 to 1998, Carter Alan had a front-row seat to the destruction of America’s vibrant and innovative radio system.

As he wrote in Radio Free Boston, “Recognized in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, this is the station that introduced new ideas that became fresh trends, and then accepted dogma… a swath of influence and innovation that dated back to Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. Refined in the fires of the sixties antiwar movement, swept into the color-splashed, pixilated eighties world of MTV, and eventually drained of its blood in the consolidated radio industry of the new century…”

What happened to bring about this destruction of WCBN and the radio industry?

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 is what happened. This act deregulated the telephone, broadcasting, and cable industries, including removing the cap on radio station ownership that had prevented market consolidation and domination. As critics predicted and an FCC study later confirmed, “the Act led to a drastic decline in the number of radio station owners, even as the actual number of stations in the United States increased. This decline in owners and increase in stations has resulted in radio homogenization, in which local programming and content has been lost and content is repeated regardless of location.”7

In other words, you get canned shows of repetitive content no matter where you live. It’s why your local radio stations suck and there are no longer any radio personalities like Carter Alan (who was a local celebrity when I lived in Boston).

As Carter watched in horror, his beloved WBCN went from a radio pioneer to “just another point of light in [new corporate owner] Viacom’s vast Milky Way.” The mantra at Viacom was maximizing revenue, with the inevitable cost-cutting and downsizing of staff. No risks allowed, the number-crunchers in charge, and literally everything having to be vetted by the corporate suits.

They “took a machete to the music library and cut it in half… plus the music became sooooo…. Vanilla.”

Of course, the rigid corporate regime meant that individuality by the music directors and DJs was stifled and “creativity became a carefully defined set of rules.” The office itself reflected this, becoming a sterile environment like a dentist’s office.

The end result, as you no doubt suspected, is that the extraordinary audience loyalty that WCBN had built up over four decades was annihilated and the younger audiences that make or break a station abandoned it in droves. In 2009, the station was axed and its doors shut forever.

Where is a band like Aerosmith going to get support in breaking into the market today and having a voice when there are no longer any WBCNs?

Maybe the music industry? Let’s look at that next.

The ‘crazy mazes’ of music industry contracts

It’s always been challenging to break into the music industry, secure a recording contract, and make a decent living from one’s music, but it appears that achieving that has become even more difficult and perilous over time, and is now nigh near impossible except for the glorious, glamorous few.

I say perilous because artists can sign a contract, write a series of hits, go on a long, exhausting tour to keep their audience sweet and reach new listeners, sell a shedload of merchandise, and yet come out the other end owing the record company money.

Cases in point:

In the sixties, see my post on Fanny and watch the Mad Dog with Soul documentary on Joe Cocker, who was the #1 male artist in the U.S. and yet by 1976 owed A&M Records $800,000 (over $4.3 million today). He was sleeping on a friend’s couch and didn’t even have enough to buy a guitar after the Mad Dogs tour.

In the seventies, read Chicago drummer Danny Seraphine’s autobiography, Street Player, to hear a similar story.

In the eighties, see recording engineer and musician Nic Briscoe’s Substack series on the music industry travails of Hazel O’Connor - part 1, part 2, and part 3.

In the nineties, let’s consult with producer and audio engineer Steve Albini, who laid out what musicians faced in an article called “The Problem with Music.”

Here’s how Steve described the process of getting a contract: “Whenever I talk to a band who are about to sign with a major label, I always end up thinking of them in a particular context. I imagine a trench, about four feet wide and five feet deep, maybe sixty yards long, filled with runny, decaying shit. I imagine these people, some of them good friends, some of them barely acquaintances, at one end of this trench. I also imagine a faceless industry lackey at the other end, holding a fountain pen and a contract waiting to be signed.

“Nobody can see what’s printed on the contract. It’s too far away, and besides, the shit stench is making everybody’s eyes water. The lackey shouts to everybody that the first one to swim the trench gets to sign the contract. Everybody dives in the trench and they struggle furiously to get to the other end. Two people arrive simultaneously and begin wrestling furiously, clawing each other and dunking each other under the shit. Eventually, one of them capitulates, and there’s only one contestant left. He reaches for the pen, but the Lackey says, ‘Actually, I think you need a little more development. Swim it again, please. Backstroke.’”

Later in the article, he shows us how bands get into debt after their first record and tour with that major label. Here are the numbers on who gets what from the money made:

Record company: $710,000

Producer: $90,000

Manager: $51,000

Studio: $52,500

Previous label: $50,000 (to buy out the band’s initial contract with a minor label)

Agent: $7,500

Lawyer: $12,000

Band member net income each: $4,031.25

As he explains, “The band is now 1/4 of the way through its contract, has made the music industry more than 3 million dollars richer, but is in the hole $14,000 on royalties. The band members have each earned about 1/3 as much as they would working at a 7-11, but they got to ride in a tour bus for a month.

“The next album will be about the same, except that the record company will insist they spend more time and money on it. Since the previous one never ‘recouped,’ the band will have no leverage, and will oblige.

“The next tour will be about the same, except the merchandising advance will have already been paid, and the band, strangely enough, won’t have earned any royalties from their t-shirts yet. Maybe the t-shirt guys have figured out how to count money like record company guys.”

In particular, Steve warned about the harmless-seeming little ‘deal memos’ the A&R guy would pull out and ask them to sign while hanging out together over beers and listening to music — that would legally obligate the band to sign a contract with that label — with no expiration date!

The music industry is populated with sharks and pirates. You might want to steer clear of that gangplank.

By the way, I’ve written a series of three novels about an 80s rock band called Pirate dealing with their rapacious record company, a divisive groupie, and other travails. I put these out a few years ago but never promoted them. In case you’re interested in a fun read, you can find them here. If you read any, let me know what you think (as I’m starting on the fourth one.)

In case you don’t think things in the music industry could be that bad now, let’s look at some more recent examples.

According to Pharrell Williams in the Hollywood Reporter, who’s had numerous hits and won 13 Grammy Awards, it’s “an industry that was never really set up for us to win… Contracts are literally like the craziest mazes ever. They’re labyrinths of information, and you literally have to be a lawyer to be able to read them fluently… If you’ve been in the business as long as we have, you learn the first ten years is just you getting run over, over and over again, and just thinking there aren’t good people in the world and there are, but they have to prove themselves good to you… You’re also in an industry where they just trendhop all day long. They trendhop, like they go from lap to lap to lap, it’s crazy.”

Substack author Brianna Bartelt had a similar experience, pressured into signing a ten-year contract at age 19 in which they “owned my name, likeness, and everything I produced creatively (music or otherwise)” and out of which she didn’t even get a record.

Under these conditions, how can an artist even think about rocking the boat with a protest song, either before they get a contract or once they’ve got one?

Riding the indie pony

“Yeah, but,” you say, “artists can take their lives into their own hands now, be independent and do it their way, put their stuff on platforms and cut out the labels and the middlemen. Right?”

Well, not exactly.

Ted Gioia points out that “streaming platforms actually make more money from subscribers who listen passively, or hardly listen at all. Meanwhile the major record labels have retreated into publishing, so they don't care about promoting new songs. The profit in creativity has declined so much, that many talented musicians abandon the field and take jobs elsewhere—I've seen that a lot lately.”

He is not claiming that “record labels and companies were not greedy in the past. I've never said that. My point is very different—namely that the greed was less destructive when labels and musicians had aligned interests. It's important to be honest about what's happening right now. So I will continue to criticize huge corporations that destroy the music ecosystem by promoting passivity, fake artists, AI slop, squeezing musicians, and abandoning new songs for old ones. I encourage you to join me in this— because the music culture cannot thrive under these conditions.”

In case you’re not yet convinced, you might want to read the comments from readers of Ted’s post on their current experiences as professional musicians:

“Things looked hopeful back in 1995, because you didn't need a publishing deal with a corporate. You had the equality of the internet. Now we are offered instant music, canned spam. Nobody is happy. Nobody is doing well.”

“Playing live isn’t the answer anymore, I retired because I was making the same money as I was in the ‘70s. Fewer and fewer venues, bloodthirsty club owners and the arena circuit is even worse, that is why I retired. The gangsters have technology on their side and have used streaming like the sword of Damocles.”

“I have been playing live as a semi-pro (because I held a day job) for 45 years… I work in niche genres like blues, folk, “Americana”, etc. The pay has largely stayed stagnant since the first day I performed for money. There are music clubs I have played at for four decades and they pay all the acts the same amount of money which has not changed at all over time.”

“My nephew in his late twenties plays in a touring metal band who have been unable to turn a profit after five years of scuffling even though they pack rooms, mainly theaters and some festivals all across the US. He still lives with my sister, his mom, because he can’t afford to rent an apartment. Every penny the band earns is rolled back into promotion, recording and touring expenses, etc.”

“I don't really understand how young musicians survive these days. Clubs used to hire musicians for a week or two, now one night is a good gig. It's been years since the musician's union had any jurisdiction in clubs. Records sales are next to invisible.”

“The pandemic was the last straw for me because over half of the venues I worked at regularly all over New England have shuttered. All the pro friends who I grew up with on the circuit are still scraping by despite touring, releasing recordings and playing in as many different acts as they can.”

“I am a professional musician, and I know a number of British, European, Anerican and Australasian composers, who are now in their middle ages, and have been building a following since their teens when MP3.com started up. After THIRTY years creative effort, and self promotion, they are today earning less than when they were students.”

“Since I likely won’t be physically able to play within the next ten years, I [can’t] continue performing and cover my expenses. If I didn’t have savings and Social Security, I’d be homeless. I really hope it gets better for the upcoming generations.”

“In my opinion you're correct, the whole Spotify system is another way to exploit musicians. You used to have to fight record companies and sometimes even music publishers to get paid properly, nowadays that concept barely exists.”

“It pretty much mirrors the American economy. There are a few people making a ton of money and getting lots of exposure, and the majority of musicians are finding life unaffordable, or need to have another profession to survive. Alleged non-profit organizations sponsor musical conferences that require expensive registrations, and instruct people on a barely existent business. Music critics write about irrelevant beefs between competing musicians. I'm sorry Drake and Lamar really don't like each other, but why should any musician care about such matters?”

“What's really amazing to me, is how much good music is actually out there. Finding it, as they say, is a whole other movie.”

“They [the platforms like Spotify] are generating more than half the content being streamed, via their bots, their AI, and collecting the revenue. The actual composers are getting their work played less and less every month.”

Yes, as these comments tell us, musicians are still making great music, but it’s becoming harder and harder for them to find an audience and make a living even if they deserve it — even if we would love their music.

They are being robbed, and we are being robbed, because the production and distribution system is completely broken. Because the oligarchs running the music platforms think they can increase profits by cutting costs to zero by using AI to eliminate the songwriters and artists.

Oh yeah? How about we abandon these platforms? How about we start our own system, whatever that could or should be?

The abandonment of the platforms appears to be happening already. The oligarchs themselves are cashing out, as Ted discusses in his recent posts.

We need to talk about a new system designed to reward artists for the risks they take. Enough of rewarding those who pillage and strip value rather than those who create it.

As Bob Lefsetz says in his latest post, “Everything is up for grabs today, EVERYTHING! And the spoils go to those who abhor and ignore the system and do things their way. Remember that.”

Or, to quote that genius Buckminster Fuller, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

Only the posh can afford to be musicians

What do musicians think about all this?

Over 1,000 established artists, including Paul McCartney, Elton John, Annie Lennox, and The Clash, have recently protested plans of the UK Government to allow the use of copyrighted music to train AI without permission of the music owner (through an automatic waiver).

In a cheekiness we gotta love, these artists have put out a silent album called Is This What We Want?. In other words, all the tracks are silence. The profits from the album will go to the musicians’ charity called Help Musicians. You can find the album on all streaming platforms if you wish to support their protest.

That’s the old guard, they’re used to protesting. But what about the new guard?

According to Bob (again, he’s very quotable), “The only people taking a stand are those with no traction. Everybody else is triangulating first. I hear it from musicians all the time, they're fearful of alienating part of their potential audience, so they stay silent. Everybody stays silent.”

Bob may not know about Sam Fender, a working class kid from Newcastle in England who’s been called the Springsteen of the Northeast. Sam puts his finger right on the problem:

“The music industry is 80 per cent, 90 per cent kids who are privately educated. A kid from where I’m from can’t afford to tour, so there are probably thousands writing songs that are ten times better than mine, poignant lyrics about the country, but they will not be seen because it’s rigged.”

This is a problem not just in the music industry but in all of the creative arts, as I know from working in the performing arts sector. Unless they have well-to-do parents, kids can no longer afford the training, fees, and unpaid internships that have become de rigeur to prepare and qualify for entry-level employment in the arts.

Sam is writing protest songs, including one called “TV Dinner” with lyrics taking down the music industry:

“Hypothesise a hero's rise and teach them all to then despise

It is our way to make a king, romanticise how they begin

Fetishise their struggling while all the while, they're suffering

In every worming memory of what they truly are”

But Sam insists that his protest songs “are not a call to arms — more a call to put your arms around your mates.”

Such is the state of protest music today.

Greatness: Who Makes History and Why, by Dean Keith Simonton. (The Guildford Press, 1994), p.331.

We will talk more about Buffalo Springfield and Stephen Stills in Part 3. “There’s something happening here, but what it is ain’t exactly clear.”

This came out around the same time as “Ohio,” in June 1970.

The Argument Culture: Stopping America’s War of Words, Random House, 1999.

By Carter Alan, Northeastern University Press, 2013.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telecommunications_Act_of_1996

We’ve kind of covered the how and why of the protest song itself. Your other readers have all chimed in brilliantly on your basic premises.

I was interested in your laying out of the artist experience itself. It was accurate. I went through a similar pathway in my journey through the entertainment maze. Initially I suffered low reimbursement, or a couple times no reimbursement. I was lucky enough to have had a friend who was in the process of becoming an attorney, and while helping me out decided to specialize in contract law. He assisted me in becoming one of those expenses that were paid prior to the artist receiving their cut. To illustrate the point. I spent some time working for G&R. In 2018 I talked to Slash at a festival in France. This was several years after I left the business. We talked about the “old days” and he flat asked me what I had been making with them. Turned out it was more than he was getting at the time.

I try to be very candid with my students regarding their economic prospects from playing music. The old expression “don’t quit your day job” comes to mind. As far as venues are concerned, in my part of the world the casino has become a prime venue for a group with a string of his from the 80s to perform at. There are also various outdoor events in the summer to accommodate them. That makes it possible to play on the weekends thus circumventing vast touring expenses. I spend a lot of time scouring the area for venues my students can perform. This summer I’m going to try to manage a few shows that charge small admissions so we can start a scholarship fund for prospective students who can’t afford to take lessons or need help purchasing an instrument. I think music lovers or music performance individuals are going to have to assess individual situations and act accordingly. I don’t think there’s a one size fits all scenario.

You do such a meticulous job with your posts. Kudos to you.

I think there a lots of reasons. Chief among them, music is nowhere near as important culturally as it used to be. It’s increasingly less likely to meet people who listen to music as an active activity—it’s treated as background entertainment, or people bounce from one track to another, one artist to another in whatever inexpensive streaming service that hardly pays the artist anything.

Combined with the watered-down remains of what used to be the music business, the consumer expectation that music should be free (or super cheap), the fractured state of media consumption and our fractured political values, and it’s not surprising that we don’t see more musical protest like we used to. Ironically, the “protest” songs I see are from awful people/artists like Kid Rock, or that terrible “Try That In a Small Town” song.

The largest artists in the world aren’t interested. They’re too busy scooping up every dollar they can, and don’t want to alienate half of their audience.